Interviews 1990 (Part Two)

Nightbreed Postscript

By Anthony Timpone, Fangoria, No 93, June 1990

"Joe Roth's perspective on the whole business of making movies has

changed. When you become head of a major studio, whatever projects

you've nurtured - and Joe did nuture Nightbreed - become very small

fry by comparison with the broader issue of running a studio.

Nightbreed, which was a small-scale movie in Fox's release roster,

got lost in the shuffle.

"What happened to Nightbreed is done constantly and to far more

experienced and far more established directors than myself. It's my

first experience, and God knows it won't be my last, but I'm going to

do my damndest to prevent it from happening again."

To Hell And Back

By John Ferguson, Video Retailer, June 1990

"I think horror movies at their best have a weird poetry to them. One of the great things that good horror movies do is that they approach the condition of a dream - and in the best dreams things never quite connect.

"One of the things I try to do in my movies and my books is to confound an audience's expectations. In Hellraiser the monsters get to express themselves. In fact the only objection New World had to Hellraiser was that the monster talked. They were saying, 'Monsters do not speak: Freddy Kreuger cracks a few one-liners but Michael Myers doesn't speak and neither does Jason.'

"When people say they do not like Hellraiser, one of the reasons is that they see it as too 'literary'. There are some graphic effects in the movie but there are also long passages where the characters are talking and relating to each other. Watching it again, one thing I noticed: that there was a weird kind of beauty to some of the images which you would not see in Freddy movies.

"I don't know if Hellraiser is necessarily a scary movie. It is intimidating and disturbing but there are other things going on in the movie outside the scare factor. I don't think people watch Hellraiser wondering which corner the monster is going to jump out of and say boo."

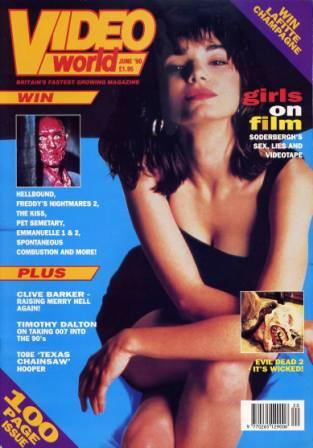

Barking Mad

By Matthew Hopkins, Video World, June 1990

[Re Hellraiser] "It's a movie for hardcore horror freaks. If you don't want to be scared out of your wits then don't mess with it.

"I've always written sexual fiction. There is a strong theme of rampant passion and uncontrollable desire going through my written

work, and the challenge was to see if I could make that work in a movie. When sex raises its head in most low budget horror

movies it's strictly as exploitation. The girl goes into the shower, the man with the ski mask follows with a machete.

"The only other place it's used is as a sort of consequence of lust subtext as shown in the Friday the 13th stories. You know

that when the guys and gals are gathered round Camp Crystal Lake, as soon as they start to take their clothes off something

terrible is going to happen to them. And the virgin always survives. What I wanted to do with Hellraiser was to give the audience

some real adult character motivations - the desire of Sean Chapman's character Frank to have an experience he's never had

before, and the desire of Clare Higgins's character Julia to have back a lover who once gave her an afternoon of extraordinary

pleasure."

Touch Of The Macabre

By Paul Cole, Birmingham Evening Mail, 9 June 1990

"People see my films and read my books and can't understand what a nice boy like me is doing with such a vile imagination. They identify me with the things I've created and think I must be corrupted. People think that someone with three heads is going to walk into the room.

"This aggression aimed at me wouldn't be there if I was writing bodice rippers or directing cowboy movies. Violence is

accepted there.

"Horror is always the easy villain to pick on, but I think that cop films where characters are mown send out worse

messages than Hellraiser or Freddy Kreuger. I really think that if you want to find out how to manipulate an audience

when it comes to cruelty see the classic Disney movies. Pinocchio is an extremely dark, vicious movie."

Clive Barker's Secret Desires!

By Michael Flores, It's Only A Movie, Vol 1 No 2, June/July 1990

"The fundamental tension is between the desire to be popular and the

desire to be right there, in the texture of culture. At the heart of

it, you can only try to be as subversive as you can. If you stay in

one spot too long, if they anticipate your next move, you will be

swallowed up. This is a difficult tension to live with. It also can

force you to remain one step ahead.

"It isn't just horror that is subversive. Any works of the imagination

are seen as threats and subversion by those who don't have an

imagination. The things that subverted my bourgeois soul when I was a

kid were works of fantasy that came from very normal material...

seemingly innocent innocent things like Disney's 'Pinnochio'. I'm sure

the guys working on it were obsessives."

How Fox Bungled Nightbreed per Clive Barker

By Alan Jones, Cinefantastique, Vol 21, No 1, July 1990

[Re Nightbreed] "Someone at Morgan Creek said to me, 'You know, Clive, if you're not careful some people are going to like the monsters.' Talk about completely missing the point! Even the company I was making the film for couldn't comprehend what I was trying to achieve!"

Clive Barker

By Allan Bryce, Video Monthly, Vol 1 No 5, July 1990

"I wasn't surprised it [Nightbreed] bombed in the States. 20th Century Fox didn't seem to have any faith in it, and they put out what was probably the worst ad campaign known to man. That said, we've been showing it to the reviewers here in England and the response has been wonderful. So perhaps we'll get some of our money back...

"I recently went on a Channel 4 programme called The Astrology Show where you get your birth sign read and all that stuff. The woman who introduced the programme said to me, 'Last year was the worst year of your life.' I said. 'You're not wrong.' Then she went on to say, 'But there's good news - that sort of bad luck won't happen again for another seven hundred years.' I liked that!"

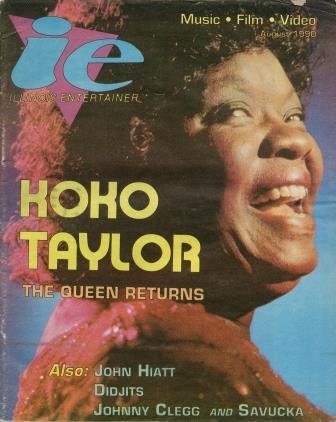

Clive Barker: Directing His Muse

By John Everson, Illinois Entertainer, Vol 16 No 10, August 1990

"I actually did a very neurotic thing and took all of the

American reviews for Nightbreed and all of the American reviews for Hellraiser and laid them side by side and I

got exactly the same proportion of reviews for Nightbreed that I did for Hellraiser pro and con - that is

60 percent con and 40 percent pro. You go into a depression no matter how hard you try - particularly when they

send you these sort of great big wads of reviews, and review after review says, 'This is garbage... This is

shit... This guy should be shot...' But what happened to [Hellraiser] is that it became a cult movie

in spite of the reviews and I think there's a very good chance the same thing will happen with Nightbreed."

"I actually did a very neurotic thing and took all of the

American reviews for Nightbreed and all of the American reviews for Hellraiser and laid them side by side and I

got exactly the same proportion of reviews for Nightbreed that I did for Hellraiser pro and con - that is

60 percent con and 40 percent pro. You go into a depression no matter how hard you try - particularly when they

send you these sort of great big wads of reviews, and review after review says, 'This is garbage... This is

shit... This guy should be shot...' But what happened to [Hellraiser] is that it became a cult movie

in spite of the reviews and I think there's a very good chance the same thing will happen with Nightbreed."

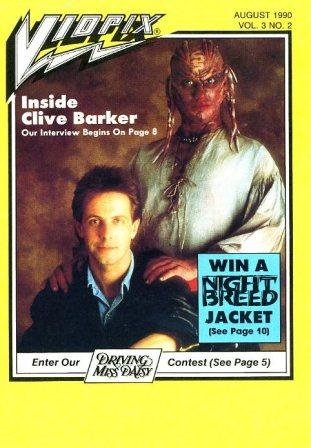

Inside The Mind Of Clive Barker

By Ed Karlin, Vidpix, Vol 3 No 2, August 1990

"Nightbreed is an attempt to make people see the world from the other side, and it's a difficult project for some people. I think that people who come to it expecting the monsters to be the bad guys have to take a little time to reassess that. When we tested the movie we discovered that the audience was quite responsive to that because there is a lot of a nagging fascination feel, a sort of attraction for the creatures of

the  darkness. Dracula is infinitely more interesting to us than Van Helsing. You would not go see a movie called Van Helsing the Movie. You would see Dracula, you would see the guy who could transform virgins across a crowded room, the guy who gets to live forever. I wanted to take that, that whole thesis, that whole fascination and just push it a little further and ask an audience to spend their time in the company of grotesques and shapechangers and be something other than repulsed. The paradox of all this is that when I showed this to 20th Century Fox, they said 'the monsters are the good guys?' and I said yes, right. 'But what are we going to do? We can't sell a movie in which the monsters are the good guys.' What happened was they put out one of the worst ad campaigns that I think has been put out for a horror movie in a very long time. Completely misdirected the audience, with the consequence that the movie never reached the audience it should have. And Media Home Entertainment, God bless them, recognized that, changed the whole way that the movie was marketed, basically selling the movie again on video. For the first time I believe they are getting it right."

darkness. Dracula is infinitely more interesting to us than Van Helsing. You would not go see a movie called Van Helsing the Movie. You would see Dracula, you would see the guy who could transform virgins across a crowded room, the guy who gets to live forever. I wanted to take that, that whole thesis, that whole fascination and just push it a little further and ask an audience to spend their time in the company of grotesques and shapechangers and be something other than repulsed. The paradox of all this is that when I showed this to 20th Century Fox, they said 'the monsters are the good guys?' and I said yes, right. 'But what are we going to do? We can't sell a movie in which the monsters are the good guys.' What happened was they put out one of the worst ad campaigns that I think has been put out for a horror movie in a very long time. Completely misdirected the audience, with the consequence that the movie never reached the audience it should have. And Media Home Entertainment, God bless them, recognized that, changed the whole way that the movie was marketed, basically selling the movie again on video. For the first time I believe they are getting it right."

Horror Master Defends Forces Of Dark Fantasy

By Mike Weatherford, Las Vegas Review-Journal, August 1990

"I use identification with the monsters very often. I like to make the reader come into a world in which all moral absolutes are up for grabs... which is usually a more interesting place for me as a writer to be.

"[My books are] not about throwing the beast out, because the beast is us. I think the connection between our darkest desires and the desires of the creatures is so intrinsic that it's naive of us not to accept that connection. We have to say that these forbidden images are inside all our heads and if we try to throw them out, we're trying to throw out something which is actually part of us."

Nightbreed : The Trials And Tribulations Of Clive Barker

By Alan Jones, Starburst, No 145, September 1990

"I wanted the movie to be a bit of Bosch: a catherine wheel of ideas shooting off sparks in all directions. I like the weird bits in Hellraiser a lot, so I wanted to make a movie with weird bits all the way through. However, I didn't realise how strange the movie in my head actually was. Nor how much genre crossing I was doing between fantasy and horror. The Fox marketing problem stemmed from its uncategorisability. Isn't that more a strength than a weakness? People seem to need a frame of reference but I didn't care that there was no Cenobite explanation in Hellraiser, only the hint of an epic back story. I still don't know how Freddy Kreuger gets into people's dreams but five movies later it doesn't matter. And who was King Kong's mother!? Who cares as long as you're having a good time?"

Delirious

By John Hind, Blitz, No 93, September 1990

"I wrote a short story once about a guy used unwittingly as a guinea pig for an aphrodisiac [The Age of Desire] and instead of clearing through him and coming out the other side, the aphrodisiac redoubled and redoubled its force within his system, until he saw the whole world in erotic terms. Eventually he ended up fucking a wall and, well... coming to death... And the reason I mention that is because I was born, in a way, as a guinea pig to the fantastique. I cannot conceive of life in any other terms but the fantastical. I don't know of any other way."

A Breed Apart

By Douglas E.Winter, Gallery Magazine, September 1990

"The whole point about vision is that it's very individual, it's very

personal, and it has to be confessional. It has to be something which

hurts - the pulling out of it and putting it on the page hurts. Now, I

don't want to name names, but clearly there are horror writers who are

simply sensationalists. It's not difficult to understand why. It's a

bit like being in the business of picking out perfect strangers and

slapping them across the face. And when asked, 'Why are you doing

this?' you answer, 'I don't know, but I'm having a fucking great

time.'

"Art can be about the individual writer's response to his or her

condition, and if that response comes out of a predigested belief

about what the audience wants to hear about the writer's condition,

then it has no truth, it has no validity. You either write with your

own blood or nobody's. Otherwise it's just ink."

Clive Barker

By Robert-Henk Zuidinga, Penthouse (Holland), No 9, September 1990 (note: translated from Dutch)

"I don't want to write a book about which people can shrug their shoulders and then put it aside. I want to write books which arouse strong feelings. If I write a gruesome scene, I people to be deathly-frightened, I want people to be able to feel and smell and measure their fantasies and to almost be able to touch what I try to create. And that I can sketch helps that. I first sketch out the monsters that I then write, so that I can see how they look, what their nature is. I said once that, if someone wanted to make a film on the basis of my tales he, without me, would be able to create those beings completely, using just what's already there on the page. That is important."

Visions Presents Clive Barker

By Andrew J. Wilson, Visions, Fall 1990

"I think it's evidence of the incredible weakness of our culture that we are in love with what we define momentarily as real. Evidence

of great health in societies, which in some (technological) senses are more primitive than our own, is that they will accept

possibilities of the dreamtime - the Aboriginal dreamtime, if you like - the notion of a condition or state of mind, maybe a state of

body, certainly a state of soul which allows the mind to eneter into and explore its condition, and the body's condition, through

metaphor, through fantasy. (I'm not using the word 'fantasy' with any pejorative meaning whatsoever, I'm using it in a celebratory

sense.) That seems to me to be great good health. It is great good health to believe, as the Hindus do, that there are 33 million

gods and goddesses in the world. It is great good health to want to understand one's dreams. It is great good health to desire the

ambiguous and the paradoxical. It is sickness of the profoundest kind to believe that there is one reality. There is sickness in any

piece of work or piece of art seriously attempting to suggest that the idea that there is more than one reality is somehow redundant."

possibilities of the dreamtime - the Aboriginal dreamtime, if you like - the notion of a condition or state of mind, maybe a state of

body, certainly a state of soul which allows the mind to eneter into and explore its condition, and the body's condition, through

metaphor, through fantasy. (I'm not using the word 'fantasy' with any pejorative meaning whatsoever, I'm using it in a celebratory

sense.) That seems to me to be great good health. It is great good health to believe, as the Hindus do, that there are 33 million

gods and goddesses in the world. It is great good health to want to understand one's dreams. It is great good health to desire the

ambiguous and the paradoxical. It is sickness of the profoundest kind to believe that there is one reality. There is sickness in any

piece of work or piece of art seriously attempting to suggest that the idea that there is more than one reality is somehow redundant."

Horror Cafe

(i) BBC TV 'The Late Show' special, broadcast on 15 September 1990 - a round table discussion with Barker hosting Ramsey Campbell, John Carpenter, Roger Corman, Lisa Tuttle and Peter Atkins (Note: filming took place on 5 April 1990) (ii) Extracts of the transcript reported by Stephen Jones, Fear, No 23, November 1990

"[Horror is] banality - the sheer banality of the culture we live in. My sense of what's scary is related to things I see around me. And what I see around me are people who want to suppress the imagination."

Gore Blimey!

By Joe Riley, Liverpool Echo, 18 September 1990

"TV is a constant regurgitation of soap operas and game shows. Horror movies offer an intense form of delerium. They are an escape from the banality of TV."

It's The Ladies Who Get Their Kicks From Barker's Brand Of Sex And Horror

By William Russell, Glasgow Herald, 14 September 1990 (note: from a regional press conference undertaken 12 September 1990)

"I have always wanted to reinvent the world. In Hellraiser it was a sadomasochistic world, in Nightbreed it is a Biblical one, because the monsters belong to a lost tribe."

The Acceptable Face Of Horror

By Fiona Beckett, The Sunday Times, 23 September 1990

"I'm aware I disappoint people. They'd like me to be a raving loony. But I don't do an interview and then gnaw on raw bones upstairs and think, 'Thank goodness I was able to cover that up.' "

It's The Kiss Of Death

By Keith Dufton, Sunday Sun (Newcastle), 23 September 1990 (note: from a regional press conference undertaken 12 September 1990)

"In my book [Cabal], the vicar was in trouble for wearing knickers, but the Americans can't handle anything sexually ambivalent so I had to make him a drunk."

Face Pack

By Nigel Floyd, Time Out, No 1049, 26 September - 3 October 1990

"I wanted to make a film [Nightbreed] in which two traditions of the monstrous came nose-to-nose. One was the '80's tradition of the arbitrary serial killer, and the

other was what I see as a much more interesting tradition, that of masks and fantasies. And to ask the audience, as it were, which they preferred.

other was what I see as a much more interesting tradition, that of masks and fantasies. And to ask the audience, as it were, which they preferred.

"But American audiences are deeply uncomfortable with material which throws into question certain fond assumptions thay have about heroes and heroines.

Some of the preview audiences, for example, were completely blown away by the fact that they were being asked to like the monsters.

"It's a straight flipping: all the authority figures - the priest, the cop and the psychoanalyst - are bad guys, and all the guys who would normally have holy water

and crucifixes thrown in their direction are the good guys. It goes back to Karloff's monster smoking the cigar in Frankenstein or watching King Kong tenderly

sniffing Fay Wray. I think those are interesting images; there's more for the imagination to play with. Instead of somebody with a machete or a garden implement

in one hand and a severed human head in the other, which isn't about anything."

Deep In The Night

By Philip Bergson, What's On, 26 September 1990

"One of the themes that fascinates me about English letters is that there is this very elaborate connective tissue between elements

of the fantastique, whether it runs through what is sometimes called the 'Apocalyptic sublime' - William Blake, Beckford's

Vathek, Byron, Coleridge - back to the more outlandish and baroque elements of Webster or Kidd or Greene - they all have

these extremes, what in later tradition would be called grand guignol, a preoccupation with physical dismemberment, extremes

of plotting against the person - daggers and poisons and secret boxes and the like - very often associated with sexual revenge.

"The images of sex and of death are very often tied very close together. I think it is a line that runs in and out of poetry and later

the novel, the theatre and a lot of painting too - Goya, Bosch, Breughel and, more latterly, Max Ernst and Francis Bacon.

"The function of the 'unnatural' in the work of someone like William Blake is to open our eyes to possibilities. In the work of most

American horror writers and film-makers, it is something to be totally repudiated and finally destroyed and there isn't the same

celebration of strangeness and darkness and the world flipped which we see in European letters."

City-Born Clive Shares His Nightmare With Us

By David Galbraith, Merseymart, 27 September 1990

"When you first see the Nightbreed, you're going to be terrified by them. But, as we go deeper into the film, the real horror emerges when the humans decide that Midian and its inhabitants must be destroyed simply because the Nightbreed are an element that they can neither comprehend or allow to be classified as in any way fitting the norm.

"The horror is a direct result of Eigerman's and Decker's ignorance and fear.

"By the end of the movie, it's the Nightbreed who'll have the audience's sympathy and it's the humans who will be seen as the monsters.

"Above ground, where the humans live, is a grey place full of fear, hatred and bigotry. When the film takes you back to Midian, I want the audience to heave a sigh and, paradoxically, feel safe."

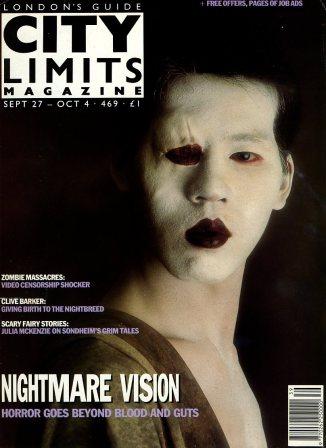

Blood's Blue-Eyed Boy

By Elizabeth J Young, City Limits, No 469, 27 September - 4 October 1990

"I am totally intrigued by the idea of creating deities and dominions, levels of reality which are  metaphors for the dream process,

the imaginative process, for the shamanistic investigation. I'm also fascinated by the idea of democratising it. The great thing

about being able to present this to people in a movie or a book is that you make available to people these imaginative journeys

which they can then do with what they will. It's their power. They are empowered...

metaphors for the dream process,

the imaginative process, for the shamanistic investigation. I'm also fascinated by the idea of democratising it. The great thing

about being able to present this to people in a movie or a book is that you make available to people these imaginative journeys

which they can then do with what they will. It's their power. They are empowered...

"We live in a very homogenised world. We live in a world which thrusts us, very early, into a position of 'be like the others, or be

called inadequate.' These are ways which are limiting and simplifying. They take out the ambiguities in us, they tame out the

paradoxes. The monstrous is a hint of variegation. Metaphorically what does this suggest? I think we're looking at the possibility

of physical change as a metaphor for psychic change. We're seeing these as signs of our own protean nature. In the film one of

the Nightbreed says to a human, 'To be smoke, to be a wolf, to live forever - it's not so terrible. You call us monsters but when

you dream, you dream of flying and changing and living forever.' Those are my dreams and those are monstrous conditions."

Macabre Master

By Pauline McLeaod, Daily Mirror, 27 September 1990

"I genuinely want to disturb people because everyone is so complacent. I have a better chance of waking people up than, say, Woody Woodpecker. I like to stir the imagination up a little, slap it across the face and maybe throw in a pint of blood - though Nightbreed is much less aggressive than Hellraiser, there is less blood and I think it is quite endearing."

Children Of The Night

By Trevor Johnston, The List (Glasgow), 28 September - 11 October 1990 (note: from a regional press conference undertaken 12 September 1990)

"The whole point of the movie was to collide two very different traditions. On one hand there's the mute masked killer like Jason Vorhees from the Friday the 13th saga, while the other strand, which I find much more interesting, is the fantastical shape-changing, almost fairy tale strain in the horror genre. I wanted to bring them together in the same picture, but have my allegiances very firmly on the side of the Nightbreed."

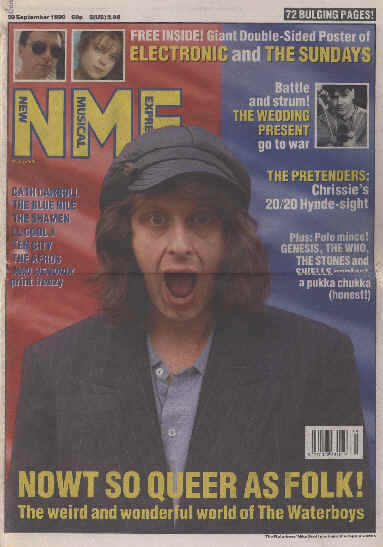

Breeding Hell

By Mark Kermode, New Musical Express, 29 September 1990

"There was a review of Nightbreed in America which said that all my movies - all two of them! - were fundamentally about forbidden sex, and

the induction of an innocent into some act of perverse sexuality. Just how easily you'd read that into Nightbreed if you didn't have a degree in

psychology is a bit of a moot point I think, but I don't think it's wrong to find that element there...

the induction of an innocent into some act of perverse sexuality. Just how easily you'd read that into Nightbreed if you didn't have a degree in

psychology is a bit of a moot point I think, but I don't think it's wrong to find that element there...

"When you're dealing with imagery and and ideas which are distressing and disturbing, and are created to stir up the mud at the bottom of

the consciousness, you have to be careful. If you're doing that, then you also have to take responsibility for its potency.

"There's only one way you can do that, because you clearly can't create while constantly worrying about the possibility that one

in every five or twenty thousand people are going to be really freaking out about this. What is important is that you have to mean what

you are saying, and you must have a motive, which is more than simply chasing the buck."

Don't Hammer The Horror

By Mark Salisbury, The Guardian, 4 October 1990

"There are certain things that define the British horror movie. There is a kind of theatricality and a kind of artificiality. I like both

those qualities because I try to bring them to my movies. American horror films tend to be more realistic, there is less of a

fantastic tradition and, for the most part, they have been set contemporarily.

"When they have been most effective is when they have been documentative - The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and The Exorcist.

Contrast that with Amicus or Hammer or even my own movies, and there is this wilful theatricality, this kind of flourish to the

whole thing. My earliest encounters in 3D with creatures of fancy were pantomimes and I've never lost my love of the tawdriness,

the unfinishedness, the raggedness.

"If you go back to Hammer movies the same thing is true, they weren't slick operators. And going back many years before that to

the Universal movies and another English director, James Whale, working with an English actor, Boris Karloff, on an English

subject - Frankenstein - Whale loved that theatricality, it was all a bit ripe, and also had this rawness to it which is tremendous,

a home-made quality."

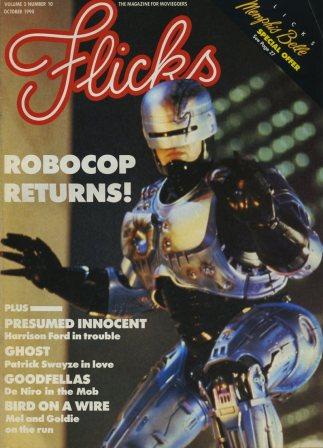

Terror In The Underworld

By [ ], Flicks, Vol 3 No 10, October 1990

"[Cronenberg]'s so witty, he's so urbane, and yet the movies he makes are visceral and dark and gut-wrenching. Doctor Decker has that duality in his life - his outward appearance is that of a cool, sophisticated intellectual, and in fact he's a serial killer."

Interview

By Georgia La Fontaine, Pond Scum, Issue 15, October 1990

"My problem with technology is that I think convenience can sometimes blind you to what you really should be thinking about. Only a very small part of the world lives in a highly technological society in which we can get access to images and can get words up on the screen and so on with great ease. Are we spiritually any more developed for that ability or are our heads simply being fiiled with spurious images of a diet of MTV and ads appearing on the television screen every eight minutes? The ability to put words into a computer with incredible speed, but increasing the mounting inability  among young people to even shape words. It's all very well to say that we have this technology - I can write a novel on the screen - but what if you can't construct a sentence in the first place!

among young people to even shape words. It's all very well to say that we have this technology - I can write a novel on the screen - but what if you can't construct a sentence in the first place!

The basic unit of exchange among human beings is not pictures, it's a word and it will continue to be a word until such time that we are telepaths and can exchange mind to mind. So I'm left wondering what these technocrats are thinking about in their tones of celebration of a visually literate society. How do these celebrants of the new age of visual literacy expect the world to work when the word and the construction of thought through the word and the expression of feeling through the word is denied because they are fixated on the image and the speed of the image?"

Lost Be My Tribe

By Mark Kermode, Monthly Film Bulletin, October 1990

"I have deliberately made both my movies [Hellraiser and Nightbreed]

slightly more difficult and less accessible than they could be. Some

of the inaccessibility of Nightbreed is a function of the terrible

circumstances under which it was made, but some of it is my aesthetic.

There are a lot of very elegantly made, well-mounted movies around

which are beautifully shaped and well performed and so on, but which

don't stick in the gullet at all. I like movies to stick in the

gullet...

"What's important is that the creator has some raw material which

lingers. Sometimes we can be too preoccupied with the general

aesthetic, and we forget that originality of vision, a risky point of

view, an outlandish fundamental notion, are finally the things by which

any medium advances."

Talking Shock (2) - Born To The Breed

By Mike Davies,

Deadline, No 23, October 1990

"The key idea that comes up over and over in my works is

the marginal as hero. They are the characters who really

understand, who have the vision. Not Mr Normal. I

don't extol the normal and the natural over the abnormal

and unnatural. That's artificial. In dreams we are

all unnatural. A little part of us is always monstrous.

"We associate creatures such as the Cenobites with evil

because of the Judaic Christian thinking which goes back

to the Israelites kicking tribal ass and making sure the

gods of every other tribe became villains or demons."

Flesh And Fury

By Mark Salisbury, Fear, No 22, October 1990

[re. Fox & Nightbreed] "The politics got so Byzantine that I didn't know who was stabbing me

in the back, who was stabbing me in the eye - but they all had knives.

All those things happen to directors all the time, but because books

aren't like that, it came as a real shock to realise that people would

just lie straight to your face and there were times

when I thought I really don't know what I'm doing this for. I don't

know why I'm bothering to deal with these people, they are total

bastards."

The Meaning Of Magic

By Mark Salisbury, Fear, No 22, October 1990

"As Weaveworld stood to the story of the Garden of Eden, [Imajica]

stands to the life of Christ. It's about what magic is really for,

and it's not for bringing rabbits out of hats. It's about the

mythology that underpins all magical activity, and when I say magical I don't mean illusions, I

mean magic in the sense of Crowley magick.

"I have been meeting and having very informative exchanges with

practising magicians in this country and in America. I treat the

occult very seriously, in fact more and more seriously, and have found

great insight into what I do from these people."

Clive Barker Interview

By [ ], (i) The Dark Side, No.1, October 1990 (ii) Best Of The Dark Side, 1992

"The excitement to me of writing a story is that it has a certain inevitability after a time. You have to tell it. It's an intimate process. Then something very miraculous happens. The book gets published, sent out into the world, and you can't predict what people are going to think about it. When it goes from your desk you don't know what you've really done, and then the flow comes back in the other direction, which is when it starts to get really interesting. That's when the fundamentalists write to you and tell you you're gonna burn in hell, or when somebody writes and says you changed their life."

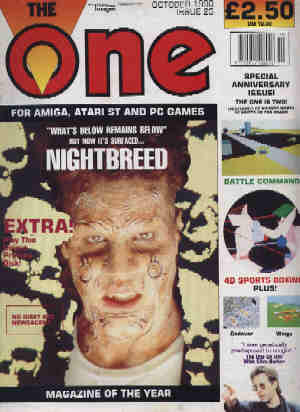

The One On One: Clive Barker

By [ ], The One, No 25, October 1990

"{Fantasy] is a form of fiction which allows you to create worlds. Once you have created a world you can put into it characters which

are more intense versions of real people - like the people you know. And you can create situations that have all kinds of emotional

possibilities that mainstream fiction simply does not allow. In short, fantasy and horror offer much more scope.

"When you write horror, sometimes things will verge on the preposterous. When you look at it clinically, much horror is deeply

absurd. But horror is about creating distressing and disturbing ideas that prey on people's underlying emotions - not necessarily

just their fears. Part of the pleasure of writing is to win the reader round to something which, viewed in the cold light of day, is absurd.

And for that to work the writer has to believe in the idea - he has to believe that it's imaginable. That basic idea is very important.

For example, Nightbreed is all about a person who goes underground, and that idea has a very ancient structure. Dante's Inferno

takes place underground. The dead are buried underground. Hell is underground...

"Once that idea has been conceived the problem then becomes a technical one as you have to put across that idea in the best way

possible. To be successful you need the marriage of two things: the right idea and then the right technical portrayal. If either is

lacking, it's not going to work."

Creating Creatures For Nightbreed

By [ ], Film Monthly, October 1990

"It was inevitable that I was going back to Image Animation with this project, particularly as it was so big - literally the creation of a small colony of creatures, each of which was different from the next. So a great fertility, a great fecundity was needed when it came to the creation of this colony."

Nightbreed

By [ ], (i) Nightbreed press pack, 1990 (ii) excerpted in World Of Fandom, Vol 2 No 9, Spring 1990 (iii) Fantazia, No 5, October 1990

"My sense was that I had to work really hard to scare

audiences, I had to put more solid 'jumps' in it than I

did in Hellraiser - it's full of those cheap little

tricks. But I also had to make sure that, when the

monsters appear, the audience will warm to them despite

their strangeness, despite the fact that some of them

are quite dangerous. If they simply bit and tore and

turned to smoke and ripped people up, the audience was

never going to come into their world. There had to be

an element of Tod Browning's Freaks in which you saw

that there was a wit and a sly warmth to these characters.

The balance to be achieved was not to let the humour

undercut the scares. In the Thirties you felt sympathy

for King Kong and the Frankenstein monster, but there

haven't been many movies like King Kong and Freaks and

Bride Of Frankenstein lately. There's no trace of that

earlier, much richer tradition and that's what the

inhabitants of Midian represent. What I wanted to do

in this movie was to set that Thirties tradition against

the Eighties tradition. You start with a stalk-and-slash

character, but this time you're going to underdstand

that this isn't something you want to applaud. I'm

saying to the audience, 'Here's the tradition you've

been applauding, but there's another tradition which is

rich and various and witty and warm and poetic. Isn't

that what we should be celebrating?'"

are quite dangerous. If they simply bit and tore and

turned to smoke and ripped people up, the audience was

never going to come into their world. There had to be

an element of Tod Browning's Freaks in which you saw

that there was a wit and a sly warmth to these characters.

The balance to be achieved was not to let the humour

undercut the scares. In the Thirties you felt sympathy

for King Kong and the Frankenstein monster, but there

haven't been many movies like King Kong and Freaks and

Bride Of Frankenstein lately. There's no trace of that

earlier, much richer tradition and that's what the

inhabitants of Midian represent. What I wanted to do

in this movie was to set that Thirties tradition against

the Eighties tradition. You start with a stalk-and-slash

character, but this time you're going to underdstand

that this isn't something you want to applaud. I'm

saying to the audience, 'Here's the tradition you've

been applauding, but there's another tradition which is

rich and various and witty and warm and poetic. Isn't

that what we should be celebrating?'"

Nightbreed - A Load Of Old Bosch ?

By Timothy Robins, (i) Fantazia, No 5, October 1990 (ii) (edited) Lime Lizard, No 1, March 1991

"I was very unhappy with two movie adaptations that had been made of my work [Rawhead Rex and Underworld/Transmutations]. I felt there was a real risk of being an author whose books were liked but who had movies that were universally despised... As I write more books, I get less worried because I think, 'Well the books will survive anyway.'"

Blue Notes

By Tyson Blue, Midnight Graffiti, No 6, Winter 1990

[Re The Art] "Projected, I think there's another two [after The Great And Secret Show]. Each of these books will be complete unto itself. This is not a serial, it's a series. You know, Pearl White is not tied to the tracks at the end of this book, with the train approaching and the audience thinking, 'Oh fuck, I've gotta wait three months or three years for the next book!'"

Clive Barker Interview

By Jon Gregory, Hellraiser, No 1, Winter 1990

"There's all kinds of ways the movie [Nightbreed] and the comic book - remember there's a comic book as well that is also taking a different direction - and the novel will interlace, and so [the reworked ending] will be fine. It's kind of an interesting challenge to watch them interface like that."

...Y Clive Barker Ascendio Al Purgatorio

By Jesus Manuel Montane, Blade Runner, Vol 1 No 1, November 1990 (note: translated from the Spanish)

"I try very hard to be detailed, to be deeply profound. For example, Baphomet is the name of a real God with real and disturbing precedent. It deals with an image which the Knights Templar of the Holy Land carried with them."

Dream Weaver

By Sue Potter, Citizen (Kent), 7 November 1990

"What I do is pass along whatever comes into my head to you, the reader or movie watcher. I sell the dream journey...

"My fears are trivial ones really, the sort we all fear like lifts, planes and rabid dogs. But my profoundest fears are of absence and nothingness, with no hope of anything...

"What I'm most interested in is the monster which looks back at us and it's ourselves."

Gore Guru

By Jeremy Watkins, Outlook, No 13, December 1990 / January 1991

"The whole idea of the shamanistic principle, that the tribe can collectively dream a solution to a problem and that the

shaman somehow indicates the direction in which the tribe heads off into their collective unconscious, to pick around

amongst the bones of old gods and return with news and indications... that's very easily parallelled with what the writer

of the fantastique is doing.

of the fantastique is doing.

"The writer of naturalist fiction is bound by definition. The fantasist says, 'Alright. I can write about divinity, semi-divinity,

gods and spirits of air and water or stone; I can write about human beings, sane, crazed, visionary or even dead; and I

can write about them all in landscapes that are very realistic or very unrealistic.'

"When you've got that range of possibilities, reality dissolves, which I think is a dream state in a kind of way.

"In our dreams we also meet the dead, we commune with gods and spirits. Whether we do that literally is an issue I

haven't yet resolved for myself. I'm tempted to think that sometimes we do, that in certain states of consciousness -

dreaming, trance states, drug states, any altered states - it's very possible that we are actually communicating with entities

other than human, at least other than living human.

"But even putting aside that possibility, which I realise marks me as a crazy, let's just assume that this is all the mind's

creation - even under those circumstances, in dreams we are learning from our subconscious which is, to take the realist

view, representing itself as the dead or the semi-divinities in order to instruct us. We are learning from those forces in

symbolic form, and growing by the exchange."

Barker Bites Back

By Anthony Timpone,

(i) Fangoria Horror Spectacular, No 1, 1990

(ii) Bloody Best Of Fangoria, No 10, June 1991

(iii) Fangoria : Masters of the Dark

"Hellraiser was also an odd movie with weird elements but New World said, 'This is a movie that Barker's made. We don't necessarily understand it or like it, but we'll get it out there.' And they took one of the movie's strongest images - Pinhead with the box in his hands - and put it on the poster beautifully. Nightbreed was packed with such images! We had 'em crawling out of our ears and the movie needed to be sold that way. Putting aside reviews, they couldn't even open a movie with 200 monsters in it."

Cabal: Plus Fort Que Spielberg

By Herve Hauss, New Look, No 89, December 1990 (note: translated from the French)

"Since the 'drug generation' rediscovered Disney's Fantasia, they understand the complete imagination of that world before them. There's an intimate bond between films for children and the total unbridled imagination of good horror films. My films, for example: I see them as Indiana Jones on acid."

Click here for Interviews 1991...