Interviews 1995 (Part One)

...Whilst Barker was busy promoting both Candyman II and Lord of Illusions (maybe you entered the 'Vanish To Vegas' Sweepstake...?) his mind was occupied with the complexities of writing Sacrament (then known as 'The Killer of Last Things'.) Complex, that is, in that he was laying both his soul and his sexuality bare for all to see - and criticise - as well as fighting with his editors to publish his work intact. A new publicist and several interviews in gay magazines allowed observers to join the previously unconnected (albeit not particularly or consciously hidden) dots ...

Redemption - Salome And The Forbidden

By [ ],

interview on video release of Salome and The Forbidden 1995 {Note :

interview looks to be taken from the same time as The South Bank Show

documentary in May 1994}

"The whole thing about making these narratives belong to you is to, in a sense, encode them. In The Forbidden what you have is almost a literal code of signs, hieroglyphs, images which were literally occult as far as the potential viewer was concerned because the only person who knew what they meant, and now I've forgotten, was me. There's always a tension in any narrative between the level of encoded material that is very personal, very private. In The Forbidden, I think we pushed to the limits of the encoded material. I'm very attracted to images which tease us with possibilities of interpretation, but make us work for them."

Let's Talk Lesbian Bondage

By Marisa Golini,

bOING bOING, No 14, 1995

"Now let's talk lesbian bondage! I actually find just about any manifestation of human sexuality fascinating, but lesbian bondage was something that I became fascinated in when I visited Japan where they do the best bondage stuff. They produce these incredibly slick, beautifully polished volumes of rather young ladies in incredibly contorted positions. I brought some of this back from Japan - and have never looked back."

Hellraiser IV / Lords Of Illusion

By [ ], Movieplex Magazine, 1995

"People regularly say to me, 'What kind of drugs do you do to write these kinds of books?' And I quote Salvador Dali, who said, 'I'm a drug. Take Me.' Something I do every morning, I do with the same enthusiasm on a Friday night sober. I can't help doing it. And if the audience for fantasy and science fiction were to disappear tomorrow, and if the only way you can keep your house in Beverley Hills is writing cowboy novels and making 'Home Alone III', I would be out of here."

Beyond Good And Evil

By Mordecai Watts, Axcess, Vol 3 No 5, 1995

"I think the idea of the illuminated picture, the illuminated story, is one that's very appealing, and I've been talking to a couple of people about that possibility. My problem is that, essentially, I'm a democrat, and I like the democracy of art. I like the paperback. I like the idea of getting these personal visions into the largest number of heads possible. I don't like, therefore, the notion of the rather rarefied, expensive edition. So what I've tried to balance off, constantly, is - how can I make a beautiful book which will be very decorated and very dense but would not be something which would seem like a piece of elitest art?"

Clive Barker

By Vince Guzman, Underscope Magazine, 1995 (note : full text online at the Lost Souls site - see links)

"I listen to a pretty fair cross section [of music]. I like Coil and Dead Can Dance and Nine Inch Nails - that area I like a lot. But I also listen to a lot of movie scores, inevitably I suppose, and I have a huge weakness for Frank Sinatra and Ella Fitzgerald. I don't listen to music when I write because it stirs me up emotionally, and I end up feeling what the music is telling me rather than what the page is telling me, so I can't really listen to a lot of music when I'm writing. But I do listen to a lot of music when I'm painting. Painting and music go together for me."

Riding The Waves With Clive Barker

By Carnell, Carpe Noctem, Vol 2 No 3, 1995, (note : full text online at the Lost Souls site - see links)

"One of the things that sex does is it makes us less ourselves.

There's something wonderful about that. There's something wonderful

about the fact that we are being transformed, in a way, in the grip of

sexual feeling. That, as we move towards greater and greater intimacy

with somebody, our personalities become less and less important to us.

In fact, in the height of lovemaking, one of the things we want is to

be erased, to be subsumed by the other person. To become, in a way,

blocked and so identified with the other person that maybe both

personalities disappear. There's something transformative and

extraordinary."

Lord Of Illusions

By [ ], United Artists Lord of Illusions Press Kit, 1995

"I think good horror movies deal with those large issues of good versus evil and light versus dark as part of their natural vocabulary. I've always tried to have some serious vein running through the entertainment, but it is, above all else, entertainment. You want to give people pleasure, but part of that pleasure should be the delicious shudder that sends chills down your spine."

![Hypno Magazine, Vol 4 No 2, [January] 1995](hypno.jpg)

Lord Of Storytellers

By David Jenison, Hypno Magazine, Vol 4 No 2, 1995

"Pinhead, Candyman and William Nix all express themselves very articulately. They speak almost poetically of their condition. The story isn't just a question of good versus bad. There's something else, and it leads to a much more interesting moral pattern in the movie than say in a Freddy Kreuger picture. While it's reasonably obvious who are the good guys, there are also shades of feeling that the audience has. I hope they feel pity for the Candyman and maybe admiration for Pinhead. William Nix, who is perhaps human and perhaps not, is in a sense a spurned lover and pissed off because his student to whom he taught all his magic ends up murdering him. So when he comes back from the grave he's really pissed. Nix gets to express that and because he does the moral picture becomes much more complex."

Clive Barker's Lurid Fascination

By Dan Lamanna, Cinescape, Vol 1 No 4, January 1995 (note : full text online at the Lost Souls site - see links)

"I've known magicians on and off right through my adult

life just by chance. And we have two real illusionists

in the movie - one of whom is Billy McComb, an elder

statesman of the magic fraternity. We retained them as

advisors as well, because we tried to be as

straightforward as possible in the way that we dealt

with the illusions; we obeyed the rules of not showing

anything we shouldn't show. And Billy was very clear

about that. At one point, when he was performing a bit

of close-up magic for a scene, he said, 'There are some

angles you can shoot this from, and there are some you

cannot. If you try to shoot it from the angles I don't

want, I won't do it for you.'

Illusionists trade on the tricks of their trade, and you

have to be respectful of the fact that they don't want

these things given away. It's a very protective

community. David Copperfield himself provided a good

example of this recently when he sued to block a writer

from revealing his secrets in a book. I suppose there is a splash

of Copperfield in there somewhere. But Swann's show is much more theatrical

than his. It's much more stagey, whereas Copperfield's

show is fairly minimalist. Swann's act is more like

something you'd see in Las Vegas.

in the movie - one of whom is Billy McComb, an elder

statesman of the magic fraternity. We retained them as

advisors as well, because we tried to be as

straightforward as possible in the way that we dealt

with the illusions; we obeyed the rules of not showing

anything we shouldn't show. And Billy was very clear

about that. At one point, when he was performing a bit

of close-up magic for a scene, he said, 'There are some

angles you can shoot this from, and there are some you

cannot. If you try to shoot it from the angles I don't

want, I won't do it for you.'

Illusionists trade on the tricks of their trade, and you

have to be respectful of the fact that they don't want

these things given away. It's a very protective

community. David Copperfield himself provided a good

example of this recently when he sued to block a writer

from revealing his secrets in a book. I suppose there is a splash

of Copperfield in there somewhere. But Swann's show is much more theatrical

than his. It's much more stagey, whereas Copperfield's

show is fairly minimalist. Swann's act is more like

something you'd see in Las Vegas.

"I don't know any of these people closely enough to say

for sure what makes them become magicians - nor would I

wish to inquire too closely. But some of it has got to

be about having power over an audience. A great magician, for a

moment, suspends everything you believe about

the world. It's an extraordinary power: they stand back

with that smug smile that says, 'Look what I did - I'm

a miracle worker!'

As a writer and director, I understand that. I'm trying

to do exactly the same thing to my audience - make them

believe for a moment that these miracles are real."

Clive Barker's Live 'Incarnations'

By Jamie Painter, Backstage West, 4 January 1995

"Theatre works more powerfully because the edits are not there. In a movie, even though you may be seeing something horrible, you know that in a while the shot is going to change. In theatre you don't have the comfort of cutting away to another shot, so there is a sense that you're watching this process unfold in front of you. [Theatre audiences] have a more intimate response or relationship with what's going on onstage...

"[Directing theatre has] certainly passed through my mind. I love the process of directing [but]... in the near future, I don't think it's possible. There are a lot of very fine directors out there who I'm sure could find ways to do these plays which would be unique unto themselves. I simply want to get the plays out there and let people make their own journeys."

Lord Of Illusion

By Charles Isherwood, The Advocate, Issue No 675, 21 February 1995 (note : full text online at the Lost Souls site - see links)

"I don't believe there are any true solutions to the world's various ills without spiritual solutions, which for me means imaginative solutions, means reaching what I think is the divine part of us - our imagination. One of the things the imagination does is allow you access to other people's lives. In imagining another person's thoughts and feelings you better understand them. It's the only way to fight the phobias that are in everybody, the only way to fight the animal impulse to view the world tribally, making everybody unlike us the enemy."

Lord Of Illusions - A Fable Of Death And Resurrection

By Simon Bacal, Sci-Fi Entertainment, Vol 1 No 5, February 1995

"[Los Angeles] is the place where the type of horror movies which were

made by Hammer and Amicus in England during the 1960s and 1970s are

now being shot. So although I'm making profits for Americans, I would

love to shoot these pictures in England - something which I've been

unable to do because I cannot secure the financial support from UK

companies. And that's a crying shame, because if one UK company had

given us $1 million to make Hellraiser, they would now be $30 million

richer. But nobody had the balls to do it because, instead of making

horror flicks, they shoot films about people who dress immaculately in

period costume and perform adultery behind closed doors. Well, if

people are committing adultery, at least one person should be killed!"

All Actor - Doug Bradley Is Not Pinhead

By Lisa Stone, Sci-Fi Entertainment, Vol 1 No 5, February 1995

"What Doug Bradley brings to the part seems to have a power over people's imaginations. As long as people are scared by Pinhead, as long as they are intrigued by him, I think there's always going to be a place for him on the screen. Good monsters never die; they just lie down and pretend to be dead for a while."

Lord Of Illusions - Filming The Books Of Blood

By Michael Beeler, Cinefantastique, Vol 26 No 2, February 1995

"That's what we're trying to do here [filming 'Lord of

Illusions'] - trying, unapologetically, to set up an

atmosphere of dread and despondency and drag our

audience into the middle of it. And it's that mingling

of fascination and disgust, fascination and repulsion,

which actually marks the good horror movies."

Candyman 2

By Todd French, Cinefantastique, Vol 26 No 2, February 1995

"He [the Candyman] invites his victims. He's quite polite about it: 'Be my victim.' Of course he pursues them relentlessly and of course he's going to get what he wants. Nevertheless there's this element of seduction in what the Candyman does. He's probably more like Dracula than any other monster: he does seduce, and he does offer a kind of immortality, which is what Dracula does."

The Conjuring Of Lord Of Illusions Part 2 - Principal Photography (1)

By Anthony C. Ferrante,

(i) Fangoria, No 139, February 1995

(ii) Fangoria : Masters of the Dark

"I think it will be impossible for me to write Harry now without imagining Scott's face. I actually started another Hellraiser short story recently and realised I was just hearing Doug [Bradley]; I just couldn't help it. There he was, speaking in my ear. I think that's fine. And Scott is a fine embodiment of what Harry should be. He's damn near perfect."

What Is Love?

By [ ], LA Village View, 10-16 February 1995

"It's sanity, isn't it? It's the thing that makes life worth living, the thing that heals the wounds, the thing which helps you deal with the sweats when you wake up in the middle of the night and realise that you're going to die. It's the promise that we won't always be separated from one another, that the skin and this business of being spirits in the flesh is a temporary condition, and that one of these days we're going to be liberated from that sense of separation...

"It can certainly be an intoxicant, but I think true love is a means by which we crystallise reality, not by which we escape it. Love is a higher reality...

"Romantic love, hearts and flowers, Valentine's Day, soap-opera love - these are hopelessly overrated. What's underrated is metaphysical love, the notion that love, in all its complexity and its darkness and its ambiguity and its contradiction, is actually a lifeline to our higher selves. That sense, that knowledge, is underrated. The fact that love is a way to touch the divine in ourselves, as opposed to being a little trophy to take away because we said the right words at the right time."

Leapcon 1995

Transcript of an appearance at Leapcon, the Quantum Leap convention, 18 February 1995

"I was told by my mother and my father - who I love but who are very pragmatic people - that my dreams would never get me anywhere, that the fantasies that I had were distractions from the business of getting on with living. Whereas I don't think that's the case at all. I think the fantasies that we have as imaginative people are the ways that we help understand reality."

Tripping The Night Fantastic

By Sheldon Teitelbaum, Sci-Fi Universe, No 5, February/March 1995

"I'm essentially writing fantasy now, not horror. Maybe in the next

five years I'll write another big horror novel, but what I'm obsessed

with at the moment is what I'm obsessed with. I just go with the flow.

I always have."

Raising Hell

By Simon Bacal, Sci-Fi Universe, No 5, February/March 1995

[Re: Bloodline] "Quite frankly, I thought Hellraiser III : Hell On Earth was the last film in the series. I mean, just how do you scare an audience with images which they've seen in three previous movies? The Elm Street series apparently indicates that you can always turn to comedy, but that's something we're deliberately avoiding because it then becomes very hard to instill true fright."

Panel Discussion

World Horror Convention, Atlanta, March 1995

"I'm doing a picture at the moment with Kathy Kennedy and Frank

Marshall, an animated feature. Kathy and Frank did all of Spielberg's

pictures and Kathy has, in her office, a perspex cube about so big,

and in it is a lot of what looks like trash, and I said, 'What is this?'

and she said, 'This is a consequence of the quarter of a million

dollars line in a screenplay.' I said, 'What is the quarter of a

million dollars line?' and she said, 'That is the house that imploded

in Poltergeist and the line reads 'The house implodes...' and it cost us

a quarter of a million dollars to make the fucking thing implode!' She

said, 'I have to keep the result,' and if you look at it there's, like,

little pieces of furniture and stuff, this beautiful model they had

made and then imploded.

"As someone who now produces movies, I know

that movies are getting more and more expensive and part of the

problem with our genre - and it's a real paradox, I don't know what to

do about this - I got into horror movies because I want to be able to

do things that you can't do in polite society, like blow John Cassavetes

to pieces. I like horror movies because they're raw and they're

dangerous and they do something to your head that True Lies and The

Mask don't do. The problem is, the more expensive a movie becomes, the

less likely they are to allow you to do that, because you are getting

to a point where it's an investment of somebody else's money. And that's

the problem - it's $10m of somebody else's money, and they want a

return on it."

Interview

By [ ],

conducted at the World Horror Convention, Atlanta, March 1995 and included

on the official video of the convention.

"I think, by and large, the horror community is a very friendly community. I don't see the kind of Byzantine intrigues that you see in other societies. The science-fiction community has, in the past, had a lot of people who have a profound hatred for each other for all sorts of historical reasons and I don't see that here."

Grandmaster Award Acceptance Speech

World Horror Convention, Atlanta, March 1995

"A couple of years ago, a really wonderful programme in England, The

South Bank Show, which is an arts programme, was kind enough to do a

profile about me. They started off with a picture of my mother and

father, who are wonderful people, sitting behind a table loaded down

with sandwiches and tea and my mother turns to my father and says, 'I

don't know where he gets it from, Len, do you?' and my father said, 'I

think he gets it from your side of the family...' which my mother

vehemently denied.

"At a certain point, I think all of us at some point in our lives

someone has said to us - a member of teaching staff, a parent, an aunt,

a sibling - has said, 'You're weird.' And you know, we are. We are. And

we should be fucking proud of it because to be weird in this gutless

culture is to be an adventurer. To be weird right now is to be on the

boundaries, to be looking into some new territory. To be weird right

now is to be brave and to be strong and to be against the flow and

that seems to me to be a wonderful condition.

"Once in a while, on a

Monday morning, when I have to go in and pitch a movie to some

three-piece-suit, one-neuron-brained executive I think, 'You know what?

He's going to say I'm weird.' Truly, I have been in marketing meetings

and movie meetings many times where people have actually said, and

this has happened two or three times in the last year at marketing meetings

for movies, 'You don't count, Clive, you're just weird, your view is

weird,' and it's a way of marginalising us - it's a way of saying,

'You don't belong in the mainstream, so therefore your opinion is a

kind of lesser opinion. The movies may make millions of dollars, but

you make the movies and then we'll talk about the public, because we

understand the public - the public aren't like you.' I encounter that

constantly, I encounter it from people - and here I come to the crux

of it - from people who are deeply, deeply afraid and they're afraid

of what's different, they're afraid of what challenges their intellect

and their emotions. They are afraid of their own imaginations because

they repress their own imaginations at the age of 5 or perhaps, more

tragically, had them repressed for them and because they're in this

repressed state, these things bubble up below the surface and do the

most terrible things to their consciousness. They are frightened

people because they can't control their dreams."

Hell's Angel

By Brandon Judell, 10 Per Cent, March/April 1995

"I think the pursuit of sensual extremes is part of The Hellbound Heart and several of

my other stories. I've always been interested in how we pursue pleasure - and how soon

the pleasurable road turns into a cul-de-sac. Then we have to turn around and look

elsewhere...

"I'm just looking at my experiences and saying, 'As a 42-year-old guy, what do I want to

get from the next twenty years of my life?' I'm not looking for another two decades of

sybaritic excess. I'm looking for some things that will feed me. I have always felt most

satisfied when I was writing or painting and taking that journey."

Horror Show: Scary Movies Rear Their Ugly Heads Again

By Frank Lovece, Newsday, New York (FanFare section), 12 March 1995

Newsday, New York (FanFare section), 12 March 1995

"Novels are psychologically driven, whereas, movies are not. A female reader will

say, 'I like the fantasy, the darkness, the shocks and the bloodletting,

but I have to know the characters as well.' A movie does that much less

well than a book, because when you enter a book, you enter people's

minds. When you turn to the movies, the character stuff is less rich,

less complex. I think also the female audience by and large is less

comfortable with the shock element and the gore of horror cinema. On

the page they can edit it in their minds, but I don't think they want

it on a sixty-foot screen."

Terror-ist

By Frank Lovece, Newsday, New York (FanFare section), 12 March 1995

"In horror movies, the audience has got to be presented with something they don't wish

to see. That's the point, really. At its best, what horror does is trap the reader or

viewer into a recognition of something they would not willingly recognize otherwise.

And that recognition is one of the great old themes of art: It's about bodily frailty,

about death, about madness, about how all things go to nothing.

"Horror movies are very aggressive. Horror stories by and large are not - they draw the

reader in. They almost seduce."

Barker's Bite

By Ron Athey,

Details, March 1995

"I wake up to the real world and it seems like a compromise. When you're a kid, the simplest things are amazing because they're new. And as we get older, fewer things are new to us. Fantasy records the newness of things... In film and writing, I use the real world as a springboard into another world. For me the clash between reality and fantasy is more interesting than just fantasy. The idea of a character who literally tastes something wonderful, then forgets it, is more interesting than, 'I woke up one day and I was a hobbit'"

The Late Late Show

Transcript of a TV appearance on The Late Late Show with Tom Snyder, 15 March 1995

The Late Late Show with Tom Snyder, 15 March 1995

"The interesting thing about Dracula is that, like Candyman, he elicits a certain amount of sympathy. For me, great monsters are not simply images of fear. They are also images that we feel a kind of ambiguity about where we're scared but we also feel we get closer to them...

"One of the great things about these kind of movies is that, if they're done well, they're very much audience participation movies. You know, you get involved. You can't sit in front of Candyman: Farewell To The Flesh and remain unmoved: even if you don't like the movie, it's going to get hold of you."

Tony Todd Returns As The Candyman

By Paige Turner, Cincinatti Call and Post, 23 March 1995

"Tales such as the psycho who escapes from the insane asylum, with the hook-handed man, are all rumors related to the listener as real events and that's what makes them frightening."

The Illusion Revealed

By Stephen Proposch,

Bloodsongs, Issue 6, March 1995

"We wanted to put the audience on notice that they weren't looking at

another Freddy picture, or some sort of tongue-in-cheek horror movie.

We were doing something that hadn't been done - certainly since the

last Candyman picture - which is to take the business of scaring people

very seriously. So it became very important to give the audience a

place of comfort in this otherwise very uncomfortable world...

"What happens is you end up, like, okay I've got Harry here but that's

all I've got, and one of the things that this movie does is take away

every other place of confort. Swann, who is potentially a very

sympathetic character, is dead after twenty minutes. Dorothea is a

character who we're by no means comfortable with; I mean, we don't know

what her agenda is at all. The cultists are doing their own thing and

Nix is doing his own thing. Butterfield and his sidekick Miller are

very far from characters that you feel comfortable with. So it really

isn't a very reassuring world that the audience finds itself plunged

into, it's not like a Halloween movie or a Friday the 13th picture

which is where you're essentially so safe that the audience logs off."

The Conjuring Of Lord Of Illusions Part 3 - Principal Photography (2)

By Anthony C. Ferrante,

(i) Fangoria, No 140, March 1995

(ii) Fangoria : Masters of the Dark

"It's a funny thing how my life is a seesaw between very private, introspective writing processes and this very public, extroverted process of directing a movie. You have to be out there and have a loud voice and speak about what you need and have a public persona, and hopefully it allows for much creative inspiration. When everybody is feeling down, you want to be a source of energy to them. You want to be the one with the smile on his face. You can be goofy, and I actually think that's an important part of this. We're all human. We may be getting tired, but we take pleasure in it. It's 3 a.m. right now. I'm tired but I'm actually having a great time."

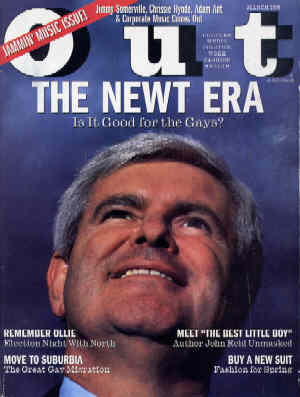

Clive Barker Raises Hell

By Gregg Kilday, Out Magazine, No. 20, March 1995 (note : full text online at the Lost Souls site - see links)

"This is a great time for the fantasist. People's minds are open and eager. It astonishes me how many people find the paranormal so normal. Of course, they're also taking in a lot of nonsense. Have you seen that chat show, 'The Other Side'? Housewives talking about giving birth to alien babies at 9 o'clock in the morning. And they call me a fantasist!"

Clive Barker, Artist

By Mark Salisbury, Empire, Issue 70, April 1995

"For me, pornographic suggests something that is essentially a pejorative. A pornographic image seeks to arouse somebody, and I certainly don't intend to do

images that are the equivalent of one-handed reading. Yes, they're often about sexual subjects but then so is my fiction. I don't know if they're horrific

images. I don't seek to horrify with my drawings or paintings. To disturb people, yes.

"I've always drawn the strange. I've always populated the canvases with creatures that were not quite human; the inhuman, the abhuman, the subhuman. I've

never been interested in painting the view from the bridge."