Fear, Love, Story... and Time

The Thirty-Seventh Revelatory Interview

By Phil & Sarah Stokes, 29 and 31 March, 1, 23 and 26 April and 31 May 2022

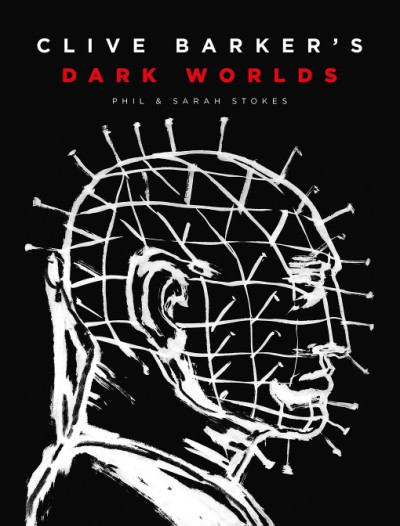

With more details over on the news page here, we’ve been hard at work on a book, Clive Barker’s Dark Worlds, which is being published by the Cernunnos imprint of Abrams Books this coming October. The book is a rich, visual journey that covers all aspects of Clive’s creative work, along with Clive’s thoughts on each area and critical and cultural analysis. We hope you like it!

Clive has also been working hard and he was keen to talk about an abundance of new stories for television and why the news on Deep Hill, Abarats Four and Five, the Third book of the Art and other projects has been quiet of late. The interview developed over several conversations, with more details on the projects we've covered below - and several others - to follow, just as soon as we're able to share them...

Revelations : "One thing we want to talk a little about today is the new book coming out from Abrams in October – Clive Barker’s Dark Worlds. So, as you know, we were approached by an editor at Abrams back in the summer of 2020 who is a long time admirer of your work and who wanted to explore the idea of a monograph that covered every aspect of your creativity over the last fifty or so years. Eighteen months on and Dark Worlds is almost locked and you’ve seen the whole book now – images and text – laid out together for the first time."

Clive : "You’ve created a mirror for me to look into, and it’s a bit of a mindblower, frankly, in the best possible way, but it’s such a mindblower that there isn’t a scale on which I can think about this that isn’t preposterous."

Revelations : "In writing the book and going through reviews of your work and reaction to it, spread over five decades, it struck us that, as you’ve often found, while some recognise the scale and extent of diversity in your media, a sizeable number of filmgoers don’t know that you write, some readers might not know how extensively you write poetry, and others may not be familiar with your painting and artwork. Then again, others know a vast amount about you and are keen to read new insight into your thoughts and processes in any medium. What do you see when you look across the diversity of work in Dark Worlds?"

Clive : "I don’t see diversity; I see a single mind manifesting its obsessions through a series of media. And I think what’s interesting is that the media, by their very qualities, bring forth certain aspects of my obsessions. Each of the media, it seems to me, has strengths and weaknesses: a novel gives you an interior life of a character, in a way that a movie doesn’t; a poem gives you incredible intimacy at certain times, in a way that even a novel can’t. There’s a sense in which the way that these things come to me, the way that these things appear in my head, are also very different. Poems can appear literally in the time that I say them – admittedly very few poems, but nonetheless I can simply say a poem as though it’s a conversation. You obviously can’t do that with a movie – at one point I think I said that writing a novel is masturbation and a film is an orgy – it’s an off-colour joke but the fact is it’s true!

"It’s not even the same for each novel – for Imajica I said the least I possibly could in advance to my publisher, and for Sacrament I gave a fairly detailed breakdown. For the two years I wrote Imajica I was entirely on my own and I never showed anything to anybody – I don’t think I even told HarperCollins what I was writing. The same with Thief, I didn’t talk to anyone editorially at all. I gave them not an incredibly detailed, but a reasonably detailed breakdown of what I knew about Sacrament, and it turned out to be a débacle, in the sense that they were appalled by what they were given.

"I want to say something new in the introduction to your book, and there’s not a tone that I, as the subject of this book, can apply to it that does not sound either hopelessly self-serving or pathetically humble. Here is this 350-page book which has an incredible sort of barrage of imagery plus extraordinary writing, your best writing, about all the projects, and the tone of the writing is amazing and I kept thinking what am I going to say that isn’t a just a redundance?

"Maybe I should address why am I obsessed with art? Two metaphysical questions: Why do I make art? Why do we make art? And are those the same question?

"I think art is more important than ever. What art does is something that remains a mystery, even though it’s been done now for ten thousand years, looking back to the images painted on cave walls. What art does in speaking both of the external world and the internal world is without precedent in the human experience. The man who drew the hunt on the walls of a French cave was speaking of himself, and of the hunt, yes? He was present in the act of reporting. He was an imperfect journalist – better than that, he was a confessional journalist. He was, in one sense, an anti-journalist because journalists are taught to be impartial.

"Now for me, and here I am approaching seventy, this mystery remains as profound as ever. I have no idea where poems come from. I was writing to someone, talking about my ineptitude with technology, and he started talking about poetry and I said, well, I think poetry is a mechanism, rhymes are mechanisms, meter is a mechanism; it should not be so difficult for me to understand how to turn on my computer, if I can rhyme ‘innocence’ with ‘in a sense’, but it is!

"Which takes me back I suppose to the nuancing of the intellect about system and scheme. The things which give me greatest pleasure as an admirer of other people’s art, and as an admirer of my own art when it’s good, is elegance of scheme: ‘Nothing ever begins…’ ‘…And this story, having no beginning, will have no end.’ Two lines, intimately connected, with seven hundred pages between them.

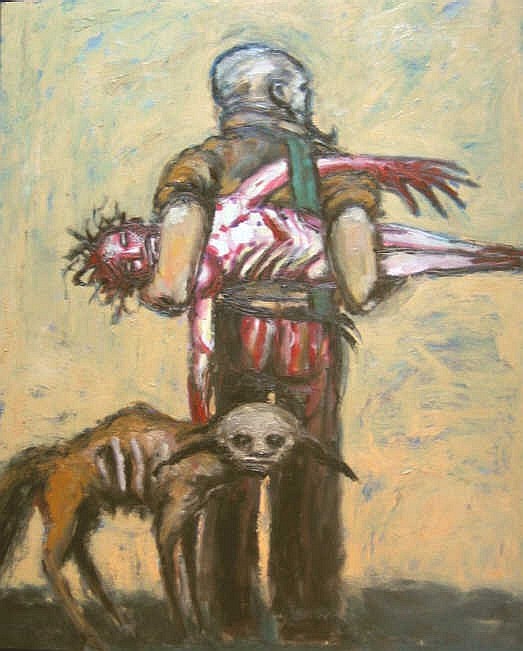

"I have always felt that the single most obvious metaphor in my work is a door being opened onto a world that you do not know – yes? And that happens over and over – metaphorically or actually on occasion – over and over and over people fall into carpets, people find themselves washed away by seas, both Quiddity and the Sea of Isabella. In the Quiddity mythology we get to the dream world where we see these visions three times in our lives. There is the symbol at the beginning of the Art book which gives you an entire system, in a way, of metaphysics, both upon the vertical axis and the horizontal axis, with a Christ figure in the middle, a crucified figure, if you will – benignly crucified, if that’s possible. I’m telling you things I know you know, but Gutenberg produced a book called the Maelstrom Grimoire in my own mythology, which actually lays out the position of all the doors. Yes, he published the Bible but the really secret thing, the thing that he was really created to print was this grimoire. The incredibly complicated metaphysic around Kissoon and the Los Alamos nuncio mythology, they’re all connected, and they’ve always been connected in my head.

"I know this is going to sound like free-association but it isn’t, in my head, I think we’re talking about the same things – I think we’re always talking about the same things when we are talking: changing genres; changing modes – everything is a part of everything else.

"I think I try, and fail very often, really try to press the body of my vision into a singularity, which it really doesn’t want to be. On the other hand, if you look at a lot of the things I’ve written: sexuality and the ambiguity of sexuality; how male can become female, how female can become male is something which comes up over and over again. It comes up in the poems: ‘Men, be women!’ ‘Men, be your mothers!’ one of the poems opines. It happens in the novels, it obviously happens in The Madonna in which Garvey wakes up to find he’s become a woman. It happened in the plays and it happened most obviously in Imajica. When I think back about Imajica, which is what, thirty years old, I’m surprised they didn’t argue about that one like they did with Sacrament!

"If I had to choose one thing that brings everything together, it would be ‘change’. Whether it would be Frank rising from the floorboards becoming corporeal again, or whether it’s Harvey turning into a vampire, or Lulu into a fish."

Clive broke off to read us a new opening to Deep Hill that he had written overnight – much more to follow on that over time – before we started to talk about his relative silence over the past several months.

Revelations : "What’s fresh and front of mind?"

Clive : "There’s a lot of things that are front of mind right now.

"There are twenty-five stories in front of me right now. I mean, I’m sitting here with every single surface that I have got around me – six surfaces, tables and a huge desk and so on – covered to capacity with either reference books or drafts of a number of projects."

Revelations : "And lots of those have moved on substantially recently and are really well advanced now."

Clive : "Yes, some of them obviously, like Mercy and the Jackal, which is ready for one last pass and then it’s off, or the poetry – same deal, people know about. But there’s a lot of things that I haven’t talked about because I wasn’t sure if they were absolutely set and going to go. And now I know they are set and are going to go so I think it’s time to talk about them and explain to some extent what I’ve been doing with my imagination for the last year or so.

"Let me say something, this will almost be my philosophy of what I’ve been thinking about television. Streaming television is changing the way we look at entertainment, no question, but it’s also, in its own way, changing in its own ambitions.

"So, I was approached by Warner Bros. last year to do a series of stories, some of which would be taken from the Books of Blood, many of which would be originals, each of which would be twenty, twenty-five minute animations. There’s a science fiction series called Love, Death + Robots which I have watched – there are two seasons of it on Netflix – and have enjoyed. I haven’t enjoyed all of them equally in terms of their aesthetics or their stories, but I think when they’re good they’re very, very good."

Revelations : "Yes, we were finding that we were responding really differently to individual episodes, which speaks to the variety of storytelling styles."

Clive : "The idea of adult animation has always been something I’ve found fascinating but I’ve never really seen it being very aesthetic. Adult animation, at least in America, tends to be about saying naughty words, you know, firstly it was Beavis and Butthead I suppose, and then more recently there’s been much more intense things but they tended to be slightly comedic. But I’ve always thought it was a place to put, for instance, In the Hills, The Cities – it’s very hard to imagine how In the Hills, The Cities gets turned into a live action feature film.

"Warner Bros. came to me, actually a man called Jason DeMarco who is head of adult animation at Warner’s, came to me and said, ‘Listen, I love the Books of Blood, the first thing I’d do is In the Hills, The Cities.’ So that’s what’s happening, that’s what we’re doing. He’s tending to take ambitious visual stories like In the Hills, The Cities but, in addition to the five stories from the Books of Blood that he named, he also wanted me to originate another six, which is what I’ve done. I don’t see any reason why I shouldn’t talk about the contents of those but I’d like to leave that to a second conversation, yes?"

Revelations : "Sure – we have lots to get through here!"

Clive : "What I would say is that my ambition for these stories was and is that they be in no way a diminution of the quality that was in the original Books of Blood. These stories, both in terms of their content and, if you like, their style – though obviously they’re not literary, they’re visual – they needed to sit comfortably with the Books of Blood stories. And I actually ended up creating eleven stories which will go into Mr DeMarco’s compendium, making a total of sixteen. He wants to do eleven at present. Their actual length is hard to be sure of but they won’t be less than twenty minutes apiece. This man is marvellous – he knows my stuff inside out and so does the man who brought me in the first place to Warner Bros., a man called Daniel Dominguez with whom I’m working on the project.

"You know, it’s a Books of Blood project so we may end up calling it The Books of Blood but it’s something that has taken an awful lot of time and creative energy because I was trying, I have been trying to create a body of stories that would be as rich and resonant as the stories in the original Books of Blood. I don’t want to feel that just because I’m writing them in words but creating them as scripts for animation that they should be in any way less powerful, less provocative, less intense, less extreme than the original Books of Blood were. I think I can say confidently that I’ve done everything in my power to make sure that’s the case. None of these are stories that I’ve talked to anyone else about, except to Daniel who I shared them with, so they’re not yesterday’s food warmed up, they’re new narratives with new ideas which are disturbing and all the things I hope the original Books of Blood were. Now, that’s one thing that’s been taking...

"Let me back up. Writing stories is a challenge, and writing a lot of stories is a challenge because my head fills with this stuff and there isn’t room for anything else, you know?"

Revelations : "Yes, it’s an important aspect of the diversity we’ve been talking about – and means that whilst people might see progress on one project, that inevitably takes time away from another project in another medium."

Clive : "That’s so right. So that was, I think, eleven stories so far, plus some which I haven’t yet developed properly. At the same time, I went to my friend Mick Garris, who I’ve known thirty-some years, and I said I wanted to do a series of television projects which would be horror stories set entirely in Britain. I wanted to go back to Britain, to the Motherland and honour and celebrate the fact that a great deal of what is absolutely central to the horror tradition originates in Britain. You know, whether it be Stephenson, who was Scottish of course, whether it be Bram Stoker, who was Irish, Mary Shelley who was English. You know we have a lot of rather less celebrated talents but nevertheless great talents like Arthur Machen; there is an incredible density of dark, dark, dark imaginative work which was created in England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales. I’m sure there are learned books that I haven’t read which pull all that together and explain that but, as I say, I haven’t read them and I thought to myself it’s weird that all this – it’s not just that it’s good writing, it’s actually in many cases the root of horror, at least in its literary form and those stories, those iconic narratives and images became the root for all the Universal Pictures narratives in the ‘30s – yes? Within this very small geographical area come an incredible density of horror images – I shouldn’t say just images – stories. These are stories which are known worldwide – there can’t be too many cultures around the world who do not know the image of Dracula, who do not know the image of the Frankenstein monster, that do not know the image of Jekyll and Hyde… it was the French of course who invented the werewolves, so we can’t lay claim to that…

"In the Books of Blood I’d attempted to write stories that were my own subgenre, if you like, you know, six books in which I would write tales in many different tones and with very many different subtexts but that when taken together would be the attempt to, to misquote Woody Allen who said ‘this movie contains everything I know about sex including several that led to my divorce…’, those original six books were all I could think about horror including several things that led to my state of mind. I wanted to come back to that again and do it for television. Why television? Because it gets to a huge audience and because I love England, I love Wales, I love Scotland, I love Ireland, though in different ways, and I thought it would be a wonderful thing to create narratives that were set in the places that I knew. I mean the places that I’ve been to in those various countries.

"So that’s what I did. I produced ten narratives which I then took to Mick and Mick said, ‘Yeah, I’ll join you on this.’ I took them to my agents and my agents sold them to Shudder.

"So it’s a series of British originals, stories of mine which Mick and I will produce – without overall title right now, but all to be set in Britain. Shudder is very, very clear that what they want is whatever you would call the Barker style or the Barker approach.

"As your phone call came through I was doing a last pass on the first of them, I suppose you’d call it the pilot, which is called London Voodoo, which sort of speaks for itself I suppose. So that’s a total of eleven plus ten, twenty-one narratives, plus Mercy and the Jackal, and the Art 3 and Abarat 4 and 5, all in my head… and Deep Hill…

"London Voodoo is done in the sense that I’ve written a thirty page summary and now we will do the teleplay which will be an hour long. The other nine of those ten stories are already summed up so what I’m saying is there’s been a period in the last seven, eight months where all I’ve done is written stories, and one of the odd things, and you know this very well of me because we’ve talked about it, when I write stories, when I start to create in that mode of story generation, a certain, I suppose it’s chemical almost, some process kicks in which makes me do more and more of it. So by the next time we talk I will give you a number but, in addition to the twenty that I’ve been talking about I’ve also generated a bunch of other stories which I didn’t intend to.

"I get into a state of mind where the creation of story becomes the only thing I can do. The only thing I’m obsessed with. I go to bed thinking about story, I can’t stop thinking about it and for the last six months because I’ve been house-ridden, partly because of Covid, partly because of not feeling good, I’ve been here every day, so fourteen hours a day, writing and I don’t know I’m going to guess forty stories – twenty plus another twenty – narratives are now extant and I can’t explain how this works or why this works it’s just that I suppose in a way I’m like a glutton who once he starts feeding can’t stop feeding. I get… everything presents itself as a form of narrative.

"The reason I want to talk about this, if it would be of interest to you and to everybody who’s reading this is because there is something about seeing things in narrative form which is something I was given, born with I suppose, and I think a lot of other people are born with it obviously, just like people are born with another form of storytelling, which is joke telling. You know, there are people I’m sure in your circle whose conversation is basically jokes – it’s another way of summarising experience but with a funny ending. I summarise experience in a different way and in the last, let’s say eight months or whatever, it so happens the world has presented me with almost endless subject matter for dark stories. This has been a very dark time in our planet’s history, and whether we’re talking about Ukraine, whether we’re talking about Putin, whether we’re talking US politics, whether we’re talking about global warming, it’s hard to keep your eyes open and look without feeling anxiety. Now, the way I deal with anxiety is by telling stories. Stories are structures which contain my unease. By putting a pattern onto that unease. Yes? It doesn’t necessarily mean that by stamping a design upon things that I’m fearful of I make the fear go away, it doesn’t work that way, but what it does do is give me the illusion of control."

Revelations : "When you say you think in a narrative form, do you think visually and then you write it down, or do you think in words and set-pieces and rhythm and cadence?"

Clive : "I don’t do either of those things, Phil. I tell in stories in images, stories in words, story is story, story is a process."

Revelations : "So you work it out of your system?"

Clive : "It’s mathematics, Phil, it’s mathematics. It’s a very complex… I used the word ‘design’ before – so maybe it isn’t mathematics; it’s geometry. There’s a theorem of story, if you will. I mean, I’m playing here a little bit but not too much, the point is, I don’t write stories with images in my head – I don’t have images in my head and then write a story about them: the images come because I am writing a story, yeah?"

Revelations : "The creation of story, all of that sounded, I won’t say idyllic, but solo, solitary."

Clive : "It is, totally solitary."

Revelations : "But when we talk about the seven or eight or past twelve months we know that you’ve had anything but a solitary life because there have been so many people wanting to talk to you about television and movie projects that it’s been a much more active and collaborative twelve months than perhaps anything in the last ten years."

Clive : "I have dealt exclusively… nobody else has been in these talks, I mean my agents have been in the ones I have had conversations in, but the deals that I’ve done I’ve done by myself and then given to my agents. The fact is that when I took this stuff back onto my own shoulders as it were, I go to bed at night exhausted as I have not been exhausted for a very long time – not in a bad way, I’ve just got too many things to deal with. I never finish the day’s work, ever. I should have had the five pages I have left to give to Mick two days ago and I was just too tired by the end of the day to do it. I’m not complaining about that at all.

"Mick is an incredibly self-effacing man and a totally delightful man but his career has often been tied in with Stephen King / Stephen Spielberg terms, very successfully. I am not tied in with either of those guys – I’m not tied in with anything but my own imagination – so there’s a difference in our approach to things. I love what Steve’s done on occasion, I certainly love what Spielberg’s done on occasion but I don’t take either of them as a model."

Revelations : "And that goes back many years, you’ve always said that it’s your take that interests you rather than playing in somebody else’s vision?"

Clive : "Completely. I mean I go back to Blake: ‘Make your own laws or be a slave to another man’s.’ You know, and this is just me speaking, I cannot see the point of spending a life, as I have, creating things and creating them in service of another man’s imagination – that just doesn’t make any sense to me. Now you two better than anybody on the planet know the frailties and the virtues of that approach. Right? I’ve succeeded and I’ve failed, I don’t know in what measure one falls beside the other but, given the choice, I’ll always pursue the road not taken. And, even in the sense that the expectations people have of me: ‘Oh, he’ll write novels of horror for the rest of his life,’ I will not exactly consciously but… I’m just not interested in doing something twice. I think that’s what it is.

"I have no desire whatsoever to create a Middle Earth. None. I have a desire to create fifty Middle Earths, and draw the roads between them – and that’s a very different thing. I think that fantastic worlds can be smothering to the creative impulse because, ‘Make you own laws or be a slave to another man’s’ is not about making a single law, it’s about making many laws. And every world I make has its own laws. All I’m saying is humanity’s imagination should be open to visit all of them."

Revelations : "The Abrams book shows, I think, that’s a theme that has followed through your body of work as a whole. It was always the case, back from when the Arts Council wouldn’t -"

Clive : "- wouldn’t fund me, yeah."

Revelations : "So you’ve been doing this forever, it’s not that you fell into something and then decided actually I’ll adopt a new model now that I’m better known, this was just your modus operandi."

Clive : "Yeah, and I think it comes from a bunch of things; it comes from that Blake quote, but it also comes from the fact that I don’t have an education in any of this: I didn’t go to literary school; I wasn’t taught playwriting; I wasn’t taught filmmaking; I wasn’t taught to paint. Now, none of that is to pat myself on the back and say ‘Hey, you did all this without help,’ because I didn’t. I had lots of help. I just wasn’t schooled in it. And, there are advantages and disadvantages to that, I think. The advantages are that you get to do your own thing. The disadvantage is that because you are doing your own thing, and inventing yourself, as it were, people don’t really like that very much because I think by and large people proceed on the basis of the similarity you have as an artist to other artists. And if you don’t have those similarities, if you are (and this is a pretentious word so maybe this isn’t the right one, but) self-invented, there’s a real danger that people won’t get you."

Revelations : "And also that they don’t have a language with which to talk about you."

Clive : "Which is, I think it’s the same thing, with respect Sarah; they’re not going to get me unless they have a language to talk about me. And my concerns are primarily metaphysical: if I had to think of one thing, if I had to think of one subject, it’s walking through a door into another world. And in that world learning that the world as you were brought up to understand it is not the world as it perhaps is. Over and over and over and over in the books and the paintings, the plays and the movies: ‘He stands before an open door,’ yeah?

"When you look at yourself through the lens of art, as opposed to the lens of biography, you realise they’re one and the same – yes? So when I started to read the book, I found myself overwhelmed by it. There are so many things you’ve reminded me of in it – I’ve never had one of these drug experiences but I think one of them gives you a life-summary, doesn’t it? Where you ingest the drug and suddenly everything comes before you in full colour and so on – that’s what it’s like! This incredible abundance, this incredible diversity. The fact that I am a singular mind viewing what seems to be a great plurality of minds is bewildering, actually, in a great way. I didn’t know how to assess what I was looking at, and I still haven’t been able to. Every page is different to the page before it, and the page that follows; every one. And the material itself is always different.

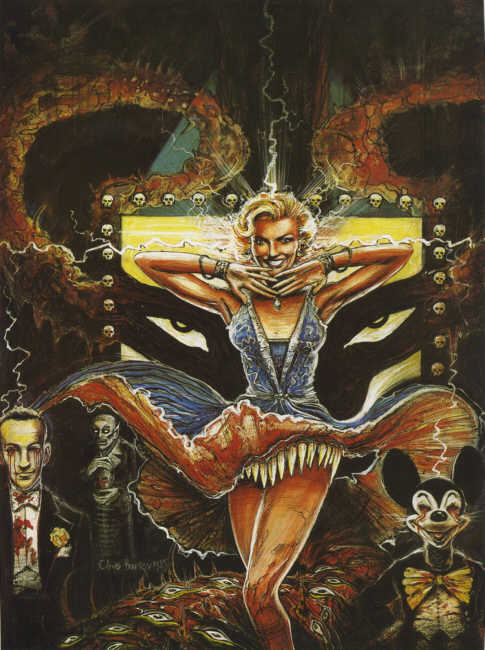

"The last time we spoke, I made an argument that I thought held water but I don’t think it does – I’ve read most of the book again since, actually last night: I said ‘all of it comes from one place, the past, the future, the dreaming moment between are all one country living one immortal day…’ Bollocks! I mean, in the long term, sure, it may be true if you look inside my head to see how it’s working but when you look at the book it doesn’t seem that way! It seems as though a cluster of faintly unstable minds have got together and told each other stories and painted pictures for each other all night! I think that the fact that the stories and images fly violently from one extreme to another – I mean, there a re pages which are all black and white because the artwork was black and white, there are pages which are brilliant colour, there are pages of ourselves as regular human beings, as it were and as spiritual being pictures. I am completely besotted by the book."

Revelations : "There’s a continuum in it, with your vision striving to be shared and to communicate to others."

Clive : "This is a big year, this is my Biblical span: threescore years and ten and all that this year has given me is appetite!

"I would like to be able to have some influence on the world, that’s what artists seek. Some artists, abstract expressionists or whatever have no desire to connect with the issues of their day, of their world. You can’t go to Pollock if Pollock were alive and say, ‘Well, how do you feel about – what’s the political value of this painting?’ There isn’t any. I have never seen my purpose as the dividing off of my art from the moral issues or amoral or immoral issues of the world. So if you go through the Books of Blood stories one by one you’ll find they’re all about something which is not ‘Boo!’ It’s also true of all the novels and I think as the novels get bigger, as you get to Imajica, I would argue I tried to make it about the eternal negated goddess but, in order to do that, in order to celebrate the eternal feminine I wanted to take it to a greater level and to talk about the things that had been suppressed that are attached to that.

"If we were to be living spiritual lives we would have a planet, we would have a future as a species. If we were alive to the fact that all things are holy, then we would not be raping and violating the planet. We would not be overfishing, I’m not even going to go into this because you know it, it’s not just about power, it’s about power at one remove, which is money, profit, which then becomes power, of course. It’s about the fact that the last fifty years have seen – again, the word – unspeakable levels of profiteering by drug companies, by armies, by police forces and so on and so forth almost all of which are male dominated bastions. I get so stirred up.

"Here I am, at the tender age of sixty-nine, wanting to be fearless, as I was as a kid, you know, and as a younger writer, and knowing there are things I want to be fearless about; stories, ideas. I think we just got to what the introduction is: what are the things that are the common drivers in my work? Fear, Love, Story… And now it’s me that needs to go away and think about that..."

Indeed, having thought about it, Clive came back to us a little while later, confessing that, far from having himself all figured out, the opposite is true. He continually re-assesses his work from new vantage points and sent us a note as he newly recognised the importance of Time across his work.

Clive : "Here’s a strange thing I learned yesterday. The failure of the hadron collider to spit out its exquisite invisible truth delayed our getting any closer to a definition of time. But a little while after discovering this — an hour, perhaps –I had an epiphany.

“It’s probably something you’ve known a long time, but it’s all news to me. The Art Trilogy, The Abarat Quintet and The Thief of Always are all stories that concern themselves with the transformation, the re-designing, of Time.

"In Abarat the hours are an archipelago, in The Art the past, the future and the dreaming moment between are one immortal day, in The Thief of Always to live a day in one house is to lose a year in another, and in Chiliad, I sit by a river that flows both to futurity and back towards a brutal ancient world, while dreaming of the dead being born from corruption to travel back to the mystery of the womb."

News - Clive Barker's Dark Worlds

Clive's television project with Mick Garris

Clive's adult animation project with Warner Bros.