Interviews 1987 (Part Two)

Scareaphanalia, No 57, September 1987

A Talk With Clive Barker

By Michael Gingold, Scareaphanalia, No 57, September 1987

"I made a slightly milder picture than I might under other circumstances have done, if it had gone out unrated. I was contractually obliged to produce an R, it was there in my contract. I wasn't about to produce an unrated picture - you know the problems of putting out unrated pictures anyway, and this is my first picture and I wanted it to be visible. I wanted this to be playing a lot of places; I didn't want to feel like I was making a minority picture.

"The downside of that is there are a lot of things you can't do; there's a lot of things that people say, 'No, I'm sorry, you can't possibly do that.' We had a lot of problems in that direction. The picture remains a hard R: it's still a tough picture, but I had plans for it to be much tougher... a lot more of the sado-masochistic stuff, a lot more of the pleasure-pain threshold stuff, which I knew that Stuart Gordon had an immense amount of problems with in From Beyond. I knew that there were dangers there, and I knew that, on a tight schedule, it was going to be really difficult to shoot stuff that the chances were I wouldn't be able to use. So, to some extent, I deliberately limited myself."

Campus Voice Encounter

By Peter Gordon, Campus Voice Encounter, Week 8, Programme 38, Autumn 1987

"What is lost often in the stalk-and-slash picture, or whatever, is any kind of underpinning, is any kind of poetry, is any sense

of the movie having any resonance. You come out of a Friday the 13th picture and you've forgotten it: it's gone, it has no nutritional

value as far as the imagination is concerned.

"There's now a sort of subgenre of picture - the House pictures would be examples of this - where basically what you're signalling to

the audience is that the genre sucks. You signal that by actually making gags at the expense of the material at the same time as

presenting the material. It's not just that those kind of movies are signalling that we don't want a scare, I think it's worse than that.

I think what those movies are signalling is that they don't believe that the idea of scaring somebody is a valid endeavour. It may

even be that those movies are signalling that they don't believe they can actually scare people any longer, it's almost like

they're surrendering before the war begins."

Snakes And Ladders

By Kim Newman, City Limits, September 1987

"The kind of material we put into the picture is not generally photographed as elegantly or as well lit as we did it. We were trying to combine this very strange, dark, forbidden imagery with really nice pictures.

"I think New World are hoping Hellraiser will appeal to people who wouldn't go to see House 2 or Creepshow 2 - the other horror films they're putting out this season - and that word of mouth will attract people to its slight off-centredness as a picture. But, there's also enough traditional stuff to attract the usual horror fans: there are monsters - in fact, there are more monsters than in, say, House. We've got the weird stuff in there as well, a lot of action. And we've got women dislocating men's jaws with hammers. I think the thing to do is go out and scare people. But this isn't a gross-out picture. It doesn't gain its maximum effect from close-ups of wounds. It doesn't look like photographs from a pathology book. We want to scare people because they're committed to the characters. So we put the characters in dire situations.

"Hellraiser is actually about a man who does a deal with the Devil - or forces beyond our comprehension - and is torn apart for his pains. His mistress, who happens to be his brother's wife, decides to resurrect him by murdering men. It's about desire. It's about people desiring stuff they can't have and the consequences of desire pressed to the limits, beyond the limits."

Raising That Hellbound Heart

By [ ], Starlog, No 122, September 1987

"Well, it's about what a woman will do for a hell of a good time."

Hellbent On Horror

By Allan Bryce, Photoplay, Vol 38 No 9, September 1987

"I've always written sexual fiction. There is a strong theme of

rampant passion and uncontrollable desire going through my written

work, and the challenge was to see if I could make that work in a

movie. When sex raises its interesting head in most low-budget horror

movies it's strictly as exploitation. The girl goes into the shower,

the man with the ski-mask follows with a machete...

"What I wanted to do with Hellraiser was to give the audience some

real adult character motivations - the desire of Sean Chapman's

character, Frank, to have an experience he's never had before and the

desire of Clare Higgins's character, Julia, to have back a lover who

once gave her an afternoon of extraordinary delight. Most horror movie

characters have motivations that are very two-dimensional and they tend

not to develop as a result of that. It's not like that here. Julia is a

very complicated character: lost, lonely, pissed-off with her husband.

She's much more interesting than your average horror movie heroine.

"We planned meticulously the way that she looked and the way she

changed. Her make-up changes, her costume changes and her hair

changes. The more blood she spills, the more glamorous she gets. Clare

gives a very legitimate performance without guying or mocking the

material. She has immense courage and a great darkness inside her. She

enjoyed doing it and had the skill to carry off the material with

dignity. There's a wonderful sense of style about what she does. It's

not a very English style of acting. But what she gives to Hellraiser

is sharper and stranger. You have to go back to Barbara Steele and

Barbara Shelley to find her equivalent - the starchy, prim lady who is

transformed into a sexy, bloodlusting vamp."

Scorpio Goes To Hell

By Philip Nutman, Fangoria, No 67, September 1987

"Andy [Robinson] has a marvelous reputation as a

legitimate actor. In addition to that fact I knew from

much of his screen work that he could do credibly

menacing roles. So it was the combination of those

two reasons that we chose him. And I'm really glad

that we did since he's great on set. Andy came up with

suggestions, inferences, with new lines of dialogue

that worked. When Larry says, 'Enough of this cat and

mouse shit', that's Andy, and it was perfect for that

scene."

Hellraiser Update

By Philip Nutman, Fangoria, No 67, September 1987

"Basically it's about a woman who wants to make love to something from beyond the grave."

A Literary Hellraiser

By Bob Morrish, Cinefantastique, Vol 17 No 5, September 1987

"I've worked [the Hellraiser screenplay] through in great detail. When

an actor asks, 'What's my motivation?' I know exactly what to tell

them. It was my novella and its been through many drafts as a

screenplay. The narrative problems were solved a long time ago."

Hellraiser

By Alan Jones, Cinefantastique, Vol 17 No 5, September 1987

"[Hellraiser]'s not an art movie, it's a horror movie, but one that is going to be made with the maximum amount of intelligence and class we can muster. I want to make sure we don't make a picture that is merely functional like 'The Evil Dead'. By that I mean where the lighting is OK, the effects are OK, but at no point do any of those departments pull out the stops and turn crap into art. We have got some extremely beautiful images in this picture. One of the things I do in my writing is, when stuff gets barbaric, the language gets very elegant. The stronger the imagery becomes, the more important it becomes to context it in a paradoxical way. That's what I'm doing here."

Raising Hell

By Paul Mathur, Melody Maker, 16 September 1987

"The backers didn't have much faith in the film until about half way through when they realised they actually had a good film on their hands. You can't escape the fact that the American market brings in fifty six per cent of the revenue whereas the British market brings in three per cent so when they decided to dub it, despite my original objections, I finally decided that I'd rather do it myself than leave it to them. In a way I think it gives the film a new perspective, takes it away from the specifically British setting (it was filmed in a house on Dollis Hill). It ends up taking place in some unspecified place West of Ireland, rather than like all those Hammer Horror cemeteries."

Queasy Does It

By Martin Burden, New York Post, 17 September 1987

"You've got to start out as you intend to continue. I want to be able to say to the audience, 'Look, you're in the hands of a dangerous man.' You should always show things a little stronger than people think they can take, push them a little bit further.

"I like to come out of horror pictures thinking, 'Boy, that was tough.' It has to be that little bit gruelling.

"[The MPAA] had a few strong words to say about the film and made us take out 20 seconds. There was one scene where Frank puts his fingers into one of his victims. No can do...

"I enjoy scaring myself, being grossed out. Did you see The Fly, when Jeff Goldblum's ear falls off? I love that stuff.

"Anyway, a reviewer said Hellraiser was only the second bloodiest picture of the season, after Robocop."

Sins Of The Flesh

By Donald J. Hutera, St. Paul Dispatch & Pioneer Press, 17 September 1987

"We all have an affinity for monsters, to some extent. The moment when Karloff smokes a cigar and listens to the blind man play the violin in Bride of Frankenstein, or the look of tenderness that crosses King Kong's face when he realises that Fay Wray is too precious to kill. Too often, those moments aren't allowed to be talked about by the monster, who is either mute or grunts. I want to give monsters the freedom to talk about themselves.

"I like hugely the clarity of debate, where Frank can say to Julia, 'We belong to each other now for better or worse - like love, only for real.' That's a monster's viewpoint, a monster's idea of what love is. It's purer than if they'd gone up the aisle together."

Barker Raises Hell Over Censorship

By Dan Novakowski, The Daily Calumet, 18 September 1987

"I don't think the stuff [the MPAA] took out was gratuitous. I don't think there's anything in my picture which is gratuitous. I think it's trying very hard to break some new ground in terms of what you can show but it's all related to the narrative. So the question always is - when you've got a shot - does the shot make sense? Does the shot illuminate something in the plot? And, if the answer is yes, I don't care how grisly, strange or gory it is if it makes sense within the narrative. We're making a horror picture, not Terms of Endearment 2...

"On the page, I'm never censored. So I come out of a situation where I've got eight novels and nobody ever told me I couldn't do something. I know Steve King talked about this when Maximum Overdrive came in for some cuts. There were rating problems with that too. He said it came as a great shock, having made a career out of going to the limit and, in some cases, I think I probably go further than Steve does in terms of what I actually write on the page, to find that there are people who are set up 'over us.'

"I use the words 'over us,' in strictly inverted commas because I don't think there's any moral or aesthetic or metaphysical superiority of these people. It's just a function we've set up in our society, that we've set up these people to look after us, to tell us 'thou shall not see.'"

Clive Barker: The Future Of Horror

By John Wooley,

(i) Tulsa World, 18 September 1987.

Re-written as No Apologies in (ii) Bloody Best of Fangoria, No 7, 1988 and

(iii) Fangoria : Masters of the Dark

"Directing has to be one of the most demanding physical jobs. Suddenly you're sleeping half as much as you normally sleep, and when you're on set, it's a question of, 'Do you want the tulips or the daffodils?' and everybody's got a tulip-or-daffodil question to ask. If you make the wrong decision, if you choose a tulip instead of a daffodil, you're responsible. It's up there on the screen, and you'll have to live with the bloody tulips the rest of your life."

British Horror Novelist Makes Directorial Debut

By Tony Frazier, The Daily Oklahoman, 18 September 1987

"I have got, to some extent, a reputation for a certain kind of storytelling on the page, and I knew very well that that

audience would be watching me very closely. I knew that that audience would be very critical of me if I didn't at least

attempt to make the story work on several levels, to sort of have the texture of the thing be the cinematic equivalent of my

written work...

"Within the very strict financial guidelines that were available to me, I feel I got a picture that has at least a stab at

capturing the flavour of the written fiction."

Raising Hell With Clive Barker

By Christopher Golden and J. Alex Schwartz, (i) The Tufts Daily, 18 September 1987 (ii) excerpt presented in Cut! Horror Writers On Horror Film, edited by Christopher Golden, 1992

"The only rule is that there are no rules... I'm as corrupted as any human being is ever going to get... and I'm happy."

Clive Barker: In The Shadow Of Eden

By Ron Stringer, LA Weekly, 18 - 24 September 1987

"In Weaveworld I believe that we're in territory that is every bit as revelatory and strange as anything else I've done. It just isn't grisly. I'm in the revelation business; sometimes the stuff that's revealed is going to be gruesome and disgusting, sometimes not...

"There is, I think, a visionary thread in my work, even in the Books of Blood, times when transcendence is achieved through those dark routes. And time and again, there's a sense of the ambiguous qualities that come from confrontations with the dark: yes, there's bad stuff out there, even lethal stuff, but there are also moments when you understand yourself better, when you understand your appetite better. The desire to confront the darkest, most forbidden aspects of our personal natures, of our sexuality, of our anxieties about death, of our fears and hopes for physical transformation... those are not necessarily all bad news.

"One of the things about the Weaveworld is that it's not a world of milk and honey. I'm writing, really, about Eden, but I don't want Eden to have an oversweet quality. I'm not writing an escapist fantasy. The Seerkind, the creatures of my Eden, are quarrelsome, they're idiosyncratic, they're very individual. In Weaveworld, they stand very strongly against the grey mass of the collective psyches of the people of Liverpool...

"As for revelations, one of my heroes is William Blake, and one of the things that he did, in Jerusalem, was take a vision of England, the England he lived in, and haunt it with spirits, with angels and devils. In Weaveworld, I've tried to make a fantasy that marries up the England I know, specifically the city I know, with such things. My feeling is, moreover, that this kind of fiction has a use. The responsibility is clearly to make it work in our world and for our world."

Novelist Barker Raises Hell On Film

By Bob Strauss, Chicago Sun-Times, 20 September 1987

"At its best, fantasy and horror fiction should be confrontational; not an escape from reality, but a metaphorical way to reveal deeper truth. I want people to associate Barker with the real world reinvented in a literary or cinematic form. Works of the imagination are finally tools for change. They're not, and should never be, substitutes for reality."

The New King Of Horror

By John Stanley, The San Francisco Chronicle, 20 September 1987

"I wanted to explore the dark night of the soul. I wanted to convey my passion for telling a story

subversive and unnerving. Good fantastique should be dangerous, leading us into dreams and night, giving

us a map of unexplored territory. A world of tension and fear in which everything goes wrong...

"Think about it: We have Elvis, Marilyn Monroe, Hitler, Coca-Cola . . . but we also have King Kong holding up Fay Wray in

his palm, Boris Karloff shambling in six-inch heels, Charles Laughton swinging from the gargoyles of Notre Dame,

and we even have that damn shark. These are images in everyone's minds. Fantastique has power and influence in

our dreams and subconsciousness, but we shouldn't seek to legitimize subversive matter. For when the status quo falls in love

with it, it is no longer subversive. You should never tame the tiger. It's wild. If you do tame it, it is no longer a tiger."

Locus, No 320, September 1987

Clive Barker Movie Problems

By Stephen Jones, Locus, No 320, September 1987

[re injunction against Green Man Productions, the film company behind Underworld and Rawhead Rex, following the lapse of option rights over four more Books of Blood stories] "I had to put in an incredible amount of work, and then Green Man didn't even bother to oppose the injunction. I think they were just bluffing. A couple of the projects have been put straight into development. I'm just pleased to have my children back..."

Barker Weaves A World Of Fantasy

By Stephen Schaefer, The Boston Herald, 21 September 1987

"Of course the creatures from Hell are an invention. I'm not making a movie or my fiction from what I believe - I'm making metaphors. This is about a woman who wants a man so much, she will murder over and over again until she gets the body and the face she wants.

"We've all of us fallen in love so profoundly we would kill for the beloved. Hopefully, this touches something true about our passions, the intensity of our obsessions when desire gets hold of us... Every now and then, you've got to do something people tell you you shouldn't...

"My fiction is about how characters reinvent their world, about world reinvention of different kinds. Frank, the dead brother in Hellraiser, is bad. And interesting and sexy and believable. And sympathetic."

Stephen King: I Have Seen The Future Of Horror Fiction, And His Name Is... Clive Barker

By Jay Carr, The Boston Globe, 21 September 1987

"Collins, my publisher, set up a publicity shot with Linda McCartney without telling her what it was for. She kept looking at me. Finally, she said, 'I just realized what it was about you. You remind me of my 10-year-old son.' She pulled out a set of black and white prints she had taken, and it was eerie. They looked like me when I was 10."

He Delights In Horror

By Kathy Hacker, The Philadelphia Inquirer, 22 September 1987

"The things I read as a kid, the feeling I had about who I belonged with... well, I always felt I belonged with the outsiders and the marginals, that was where the truth lay...

"Most of us, early on in our lives, are taught that there is such a thing as 'the real' and another thing called 'the unreal.' We are taught that our imaginations are, somehow or another, 'the unreal.' I don't know whether we actually lose it or whether we are just embarrassed or shamed or bullied into believing it's less important than having a mortgage, two cars and state-of-the-art video equipment. And, finally, what does it matter about that? I prefer to have the beast I met on the stairs when I was 4...

"I have no taste for reality. I can't get into reality. Come to think of it, I don't believe I know what it is."

Master Of Gore Lands $1 Million Coup

By [ ], Today, 23 September 1987

"I'm coping, and coping well, by ignoring the success and the money... All the things I might have yearned for when I was on the dole have been coming anyway, as a by-product of success. I'm being flown backwards and forwards from New York and Los Angeles, I'm drinking champagne and other people are providing it. I can't honestly think of anything I want."

Who's Afraid Of Clive Barker?: The Titan Of Terror And His Studies In Dread Reckoning

By David Streitfield, (i) The Washington Post, 30 September 1987

(ii) Clive Barker's Shadows in Eden

"I was very aware that if I was going to rise I was going to have to be

a proselytiser for my work. I'm aware that many writers are actively

reluctant to do that. They don't like to do public readings, they don't

like to do television and so on. But I come out of a different

tradition than the guy who wanted to be a writer from the age of six

and never did anything else...

"I have, no pun intended, something of the carnival barker in me. I'm

more than content to stand up in front of my particular tent and say,

'We got thrills, we got spills, we got rides,' you know? I don't have

any embarrassment about that. If I spend nine months writing Weaveworld

it becomes important to get it into the hands of as many readers as

possible...

"What it does, it does. I will do my damndest. I will go on the

chat shows, I will talk on radio, I will juggle peanuts - whatever it

takes to make people actually go out and buy the book. But once I've

done my best, the book will have to stand on its own.

"Finally, even publishers will say that what's important is a book

that consistently sells, rather than a book which goes 'bang!' and

then dies. I would much prefer writing a book from which people can

still get pleasure in five years' time or ten years' time, because

they can go to the library or a bookstore and get a paperback edition."

Interview

By Don Swaim, (i) CBS Radio, 30 September 1987, (ii) unedited online audio at www.wiredforbooks.org

"I don't believe that there are worlds which take us away from our own, I think they are finally worlds which help us confront our own. I think good fantasy and good horror fiction; good fantastique fiction (by which I mean science fiction, fantasy fiction, anything which is the literature of the imagination) is finally a way of offering metaphorical solutions to the world in which we live. I think bad fantasy is merely escapism - and I use the word 'merely' intentionally; I mean it as a pejorative. I think any book which you escape into and come out of feeling as though you haven't really learnt anything which is going to help you confront the life that you live outside the pages is not a particularly useful or fine piece of work. I think the responsibility of the writer of fantasy of horror fiction is to actually offer up metaphors which help us explain living to us, explain being to us and fantasy can be remarkably adept at doing that because at its best it kind of straddles a sort of dream world and the world which we occupy. And I think that sort of sense of being able to synthesize the world of our imagination, the world of our dreams, the world of our hopes for heaven and the banality and the grind of day-to-day life I think is very instructive, can be very instructive and very useful."

Time Out, London, No 893, 30 September - 7 October 1987

Clive Barker - Mama Pus (Extract From Weaveworld)

By [ ], Time Out, London, No 893, 30 September - 7 October 1987

"After seven books of horror and Hellraiser, I thought there was a real danger of people thinking,

'Oh Barker, he can only disgust us,' so I made the move to fantasy...

"I hope Mama Pus will prove I haven't lost the ability to disgust, but I think there's a lot more

in there which is fantastical and visionary. Weaveworld goes into the dark areas of horror fiction,

but it also goes into the light which horror fiction can't do."

Clive Barker: Renaissance Hellraiser

Barker at 1986 World Fantasy Convention,

by Leanne C. Harper,

(i) The Bloomsbury Review, Vol 7 No 5, September/October 1987

(ii) Clive Barker's Shadows in Eden

"'Peter Pan' is, I suppose, the book I would

want to be buried with, that dream place to which we can

go where there are pirates and Indians and mermaids and

lost children and redemption and home, a kind of

alternative home... The beautiful pain of that story is

at the basis of what I want to do in fantasy. I want to

examine how we deal with... the problem that, if we

embrace Neverland too strongly, we are forever sucking

our thumbs, but if we die without knowing Neverland,

we've lost our power to dream. Paradox, problem,

great, wonderful problem, exciting wonderful

problem."

"'Peter Pan' is, I suppose, the book I would

want to be buried with, that dream place to which we can

go where there are pirates and Indians and mermaids and

lost children and redemption and home, a kind of

alternative home... The beautiful pain of that story is

at the basis of what I want to do in fantasy. I want to

examine how we deal with... the problem that, if we

embrace Neverland too strongly, we are forever sucking

our thumbs, but if we die without knowing Neverland,

we've lost our power to dream. Paradox, problem,

great, wonderful problem, exciting wonderful

problem."

Hellraiser

By [Stephen Jones], Hellraiser Electronic Press Kit, 1987

"There are going to be moments where the audience is going to be stunned by the elegance and the beauty of the image at the same time as being apalled by the subject matter and that's a very interesting tension and paradox."

Hellraiser

By [Stephen Jones], Hellraiser US press kit 1987

"Hellraiser is unapologetically a horror film. I hope it's going to have an impact

simply because it deals with the same areas of passion and perversity which mark my

fiction. We've got a story that is emotionally very involving, motivations which are real

and, I think, performances which are tremendous. Adding further to this sense of realism

are some of the most outre and outlandish monsters to have been seen on the screen for a

very long time.

"It's an intimate, intense picture with high definition performances, gorgeous

cinematography, brilliant special effects... and a bloody great story."

Hellraiser

By David J Howe, Starburst, No 110, October 1987

"We were trying to do something that wasn't just monsters with

sharpened teeth. We had a real problem trying to produce creatures

that were original. One of the things that I don't like about horror

movies in general, is the way that themes emerge. You go through a

whole series of pictures which use bladder effects, or ones with

transformations or ones with hockey masks and all these films get

lumped together and categorised. So I spoke to Bob Keen, our make-up

effects designer, and we agreed that we would do state of the art stuff

if we needed to but that we wouldn't try and seek out designs just to

show off special effects. What we ended up with was a mixture - the

re-birth of Frank at the beginning of the picture was real state of

the art stuff but the Cenobites were created with prosthetics. They

used techniques which have been used before, it's just that they used

them particularly beautifully. I felt that they should imply that

they have a whole culture and we're just seeing the bit of the iceberg

that's above the surface. I think it's always intriguing when that

happens. I'm also much more interested in monsters that talk and

reason. Our Frank in Hellraiser has an awful lot to say for himself,

and I like that. I think that dialogue from monsters is much more

interesting than having them chase after the heroes. What we've got

here is the monster doing the talking and as a result you get inside

his head. When Frank says 'We belong together, you and I, for better

or worse, like love - only real', that's his own cynical point of view

and I'm really interested in that because too often the beasts get the

dull end of the wedge."

Eroticising The World

By G. Dair,

(i) Cut, Vol 2, No 10, October 1987

(ii) Clive Barker's Shadows in Eden

"I'm confident in my own complexity and that really interests me, because of the ambiguities of sexuality, the ambiguities of metaphysics and the metaphysics of sexuality are things which hugely influence what I write."

Horror Author Barker Makes Directing Bow With Hellraiser

By Ed Kelleher, Film Journal International, October 1987

"I'm very proud that this is not a sexist picture, at least not in the classical sense. Horror movies are immensely sexist. Women tend to have very little between their ears in horror movies. They go into cellars when the torches are failing or better yet without a torch at all, while there is a deformed man in a hockey mask with a machete in the house. While running through the woods, they always trip, that's very important. They do all kinds of very dumb stuff over and over again.

"Our two female leads, both of whom are really strong characters in themselves, defy all of that. Kirsty behaves in a way that is really intelligent most of the time. She doesn't have any wet T-shirt competition scenes. She fights back in an intelligent way. Julia has got all the fun of moving from this nice bourgeois woman unhappy with her life to Lady Macbeth, and in the middle she's got a couple of romantic scenes with a skinned man. All of which Clare plays emotionally straight. There's no point at which I feel she signals this stuff is fundamentally dumb, because she doesn't. We all got together and said, 'Okay. we're making a genre picture but, Jesus, we're going to make it with the same emotional commitment which we would bring if we were making Terms of Endearment II.'"

Tricks And Treats

By Vincent J. Sgro, Playgirl, October 1987

"My mind's eye is very graphic. I can see everything. I see it hardcore. Both [sex and horror] are

centrally preoccupied with the body. Horror fiction is very often about control. About

controlling the obsessive, the possessive, the forbidden...

"What do I do on Halloween? I write. You see, I don't believe any of the stuff in the real world, so it doesn't

mean anything to me."

The Horror

By Craig Tomashoff, (i) Boston Magazine, October 1987 (ii) short piece extracted in The Art of Horror, 2015 edited by Stephen Jones

"I'd say zombies are the ideal late 20th Century monsters. A zombie is the one thing you can't deal with . It survives anything. Frankenstein and Dracula could be sent down in many ways. Zombies, though, fall outside all this. You can't argue with them. They just keep coming at you. Zombies are about dealing with death. They represent a specific face of death. And the fact that we can even talk like this about a horror-movie creation puts down the theory that the genre can't be taken seriously."

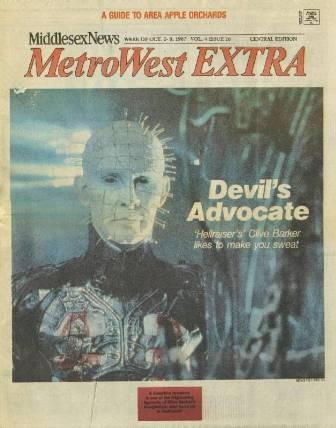

Devil's Advocate

By Craig Tomashoff, The Middlesex News, 2-8 October 1987

"A lot of people have weird, taboo things gnawing in their head. Horror fiction offers the chance to live out those things vicariously. If you get drunk with anyone, they'll start confessing some very scary things. For instance, they might tell you how they'd like to murder their wife. Or how they actually have murdered their wife. There's almost something therapeutic about letting these feelings out in horror fiction...

"I know there are a lot of people who will go see Hellraiser just to see the state of the goo, but I consider this fantasy form of fiction useful only if it connects with the way we live. The metaphors have to make emotional sense. I don't think of myself as a writer of horror fiction in the sense that I'll do anything to make you sweat."

Horror Master Directs With A Vengeance

By Vernon Scott, The Sun Sentinel, 2 October 1987

"The content of horror films has changed dramatically, you have to

meet audience expectations. A director can't make a film without

unveiling the beast when the thing shambles out of the shadows. My

books are based on the fact that I show stuff. I don't back away. I

write graphic horror fiction with elegance and intelligence. And that's

how I've directed Hellraiser.

"Alfred Hitchcock was a master of suspense and thrills, but his work

was in a different tradition to horror. I take advantage of the

wonderful advances in special effects to create fantastical monsters

that are supposed to be seen. The horror market has demanded more

graphic, complicated and sophisticated monsters. They must be seen

clearly. 'Alien' would be unthinkable without showing the alien. I

want to count the tentacles. I say, 'Show Me! Show Me!' All you have

to do is compare the original versions of 'The Thing' and 'The Fly' with

the remakes to see how much better horror is done these days.

"There never has been a time when horror pictures weren't popular.

They're not about to disappear like westerns because there are so many

varieties in the genre. I've made my movie emotionally intense and

claustrophobic. This is a much grimmer picture, for instance, than

'Re-Animator', which was done tongue-in-cheek. Hellraiser was meant to

be spookier and more serious. The best horror films touch on serious

matters, death, obsession and insanity."

Raisin' Hell

By Dave Dickson, Kerrang, No 156, 3 October 1987

"The worst thing in the world is a human desire gone sour. In Hellraiser we've got Frank, the guy who's come back from the dead, reneging on a deal motivated by very human desires. He's tired of sex, he's tired of desire as it can be experienced on Earth - so he's gone to get something which only an out-of-the-world experience could offer. And that, I think, is a very human response, to go to the limits, or, indeed, beyond... Hellraiser has actually got a human heart. I would hope that people who'd maybe reject 'Friday the 13th' as simply a piece of graphic exploitation might be tempted by the fact that this has got a storyline."

Raising More Hell

By Matthew Costello, Los Angeles Times, 4 October 1987

"A number of reviewers weren't happy with the [American] dubbing [on Hellraiser], and I wasn't either. But New World felt it was necessary. Also, the picture was too much for some people... and I was real pleased by that."

Horror Writer Was A Normal Kid, With A 'Weird Imagination'

By Judi Hunt, Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 7 October 1987

"I just had, and still have, a weird imagination. I could lie on my back looking at clouds and see things that other people never saw... My imagination gave me a power I might not have had otherwise. I mean, here I was, a short, fat, wimpy kid who wore glasses, ran into walls out of clumsiness and wasn't any good at sports, but I could elaborate on the things I read and give them a new twist, a different way of looking at them...

"Actually, this book [Weaveworld] and all the others really began when I used to go to the Mersey and watch the ships sailing past me. I knew each was going to some kind of dream place, and I'd make up stories about that place.

"Add to my daydreams the stories I read, especially Peter Pan, and you can see where it started. I was obsessed by Peter Pan as a boy, and I love that story still, especially the part where Captain Hook is eaten by the crocodile."

Shocker! Barker Cuts The Gore

By Jonathan Cooper, USA Weekend, 9-11 October 1987

"Serious alcohol may have had something to do with [seeing a world in

a rug], but I wanted to root my fantasy in something that everyone can

relate to... [Weaveworld] is a world of burying friends in the muds

and solid grief. In a way, it is more earthy than the Earth itself.

"I find sexuality much like I do death or the notion of a meaning to

life, a puzzlement. I write to find a solution."

Master Of Horror Clive Barker Turns His Hand To Fantasy

By Ruth Pollack Coughlin, The Detroit News, 11 October 1987

"For me, horror fiction is a confrontation with things which are metaphors for internal anxieties, fears which cannot ever be expelled or exiled.

"For instance, the erotic elements in my books are very much about sexual anxiety and obsession. These things can't be healed, but they can be explored, and through the act of exploring, a peace can be made...

"Making peace with The Monster is part of my work. I think there's a certain kind of fascination with The Monster: there's love and revulsion. That's why, in part, there are mass murderers who get passionate love letters and marriage proposals.

"Along with the fascination, there's a mystery. Often, when my characters confront The Monster, they might die in that act of confrontation, but they will have had an epiphany. We all look for a way in which there is some sense of the world being transcended."

Hail To Macabre Fiction's New King

By Willy Diaz, The Record, Northern New Jersey, 11 October 1987

"I like writing about women with power and sex is both a great joy and a great anxiety in my fiction...

We are erotic creatures. Sexuality is a part of our daily lives, and it's something that is not written about...

"When Dracula enters the bedroom of the Victorian virgin, her sexual attraction - her desire to be taken by the great

dark stranger who will show her a sexual adventure that will actually transcend death - is part myth, part fact. There

you have a physical creation that touches some psychological truths in many of us. The good monsters are both

internal and external. If they don't ring a universal bell, then the monster doesn't work."

Prince Of Horror

By Vern Perry, The Orange County Register: Show, 18 October 1987

"I don't believe some abstract evil is screwing our lives up, we

screw up our own lives. Other human beings screw our lives up for us and we

sometimes aid them by voting for them. I don't believe there's some great

malfeasance that means us nothing but harm. Chance, circumstance, accident,

but mainly human malice are what bring us down...

screw up our own lives. Other human beings screw our lives up for us and we

sometimes aid them by voting for them. I don't believe there's some great

malfeasance that means us nothing but harm. Chance, circumstance, accident,

but mainly human malice are what bring us down...

"In works [with an abstract evil] there's always a Christ figure to go to and say this is

the touchstone of good. I don't believe people have such touchstones in

their world. I don't have a touchstone of good. I don't have an absolute

good that I can go to. I think we're all winging it morally all the time. We do stuff we're

ashamed of. We do stuff we're pleased with ourselves for. We do stuff that

accidentally causes harm. And we do things, equally accidental, that cause

good. We're human beings. As far as I'm concerned, fantasy fiction

shouldn't try and escape the responsibility of telling the complex truth by

escaping into artificial dichotomies."

The King Of Creepy-Crawly

By Kathy Hacker, Houston Chronicle, 18 October 1987

"One of the great values of horror fiction for

me is the way it can subvert the cliches of 'Well, I'm human, therefore I'm

good' and 'You're alien, therefore you're bad.' Devastating and dangerous

cliches. 'Monstrousness,' if the word is being defined as a kind of moral

negative, a pejorative, can reside in things as human as you and I. And

great good-heartedness and the capability of full love and loyalty and

devotion can reside in things that don't resemble us at all - as, for

instance, they reside in our dogs...

"Horror is the only thing I can do, that's the bottom line. I have no

taste for reality. I can't get into reality... Come to

think of it, I don't believe I know what it is.''

The Last Resort

By Jonathan Ross, The Last Resort, 23 October 1987

"The first three [Books of Blood] took about 18 months. There's a line Woody Allen came up with when he made a movie called Everything You Always Wanted To Know About Sex But Were Afraid To Ask that the movie contained all the funniest ideas that he knew about sex, including several that led to his divorce - and I wanted to do the same thing with horror. I wanted to put all the nastiest, weirdest, most erotic, perverse ideas I could into a collection of short stories...

"The first three [Books of Blood] took about 18 months. There's a line Woody Allen came up with when he made a movie called Everything You Always Wanted To Know About Sex But Were Afraid To Ask that the movie contained all the funniest ideas that he knew about sex, including several that led to his divorce - and I wanted to do the same thing with horror. I wanted to put all the nastiest, weirdest, most erotic, perverse ideas I could into a collection of short stories...

"I like to show everything: in the books, in the film, I want to be able to detail everything. If there's a monster comes on, I want to know how many heads it's got - the audience needs to know. "

Gory Be! The New King Of Blood

By Linda Smith, Sydney Sunday Telegraph, 25 October 1987

"The film is not simply an excuse for a bunch of special effects. It does require actors, some kind of emotional root. I think we have people with real human feelings, real human sufferings and then 'bang!', right in the middle of this we erupt with these extraordinary events. The two things are tied in quite closely.

"What really fascinates me is how people in real life deal with an eruption like this. So it is important to show the human characters as real and then say, 'Now look, deal with this.'

"But the horror is a description of the response rather than an intention. I don't think to myself, 'This is really going to horrify.' What I think is, 'This is an image that suits the story, that is weird, exotic, bizarre and imaginative' and one of the side issues of that is that people are going to go 'Aaargh! That is awful.'"

Author Clive Barker Is Mild In Fact, A Horror In Fiction

By Maureen Harrington, The Denver Post, 25 October 1987

"Weaveworld isn't as bleak in outlook as some of my other stuff. It is a return to my childhood in that there is a sense of hope, a hope for an enchanted world...

"In my mind, I'm never far from that state so common to children, in which they are about building caves underneath tables and living in their imagination with invented worlds more real than reality.

"When William Blake, my favourite poet, talks of telling his parents that he sees angels in the tree, I understand exactly.

"I don't feel the schism between reality and imagination that is part of what is called 'growing up.' That is the saddest loss of childhood's passing, letting go of fantasy...

"I want to step into another world, or at least take this one and rearrange it in such a way that makes us question all our conventions. I want to push the bounds of taste and go for those instinctual fears we all suffer."

Barker's Searching For A Higher Plane

By Bob Strauss, (i) The Fresno Bee, 25 October 1987 (ii) The Illustrated Clive Barker (as 'Clive Barker - The Author') (iii)The Toronto Sunday Sun : Showcase, 30 October 1988 (Rewritten as 'Clive Barker : New King of Gore')

"One of the reasons horror fiction falls shy of being considered serious writing is that there's a general belief these kinds of stories have sexuality as their subtext, and by bringing that subtext into the more prominent position of text, you somehow call the bluff of the machine that made the thing work in the first place. You've pulled the hood off, so to speak, and people feared that in showing the workings, the magic wouldn't work any longer. I don't think that's true at all - it doesn't stop me, certainly. Any genre that requires the willful disregard of certain facts that we all know to make it work is moribund by definition."

Clive Barker - The Director

By Bob Strauss, The Illustrated Clive Barker, 1987

"I feel I write happy, optimistic stories. I write a fiction of transcendence, metaphors for transcendence. The upside is that people get new information about the way that they are in relation to their flesh, their desires, their vulnerability, their spiritual potential. The bad news is, this stuff will kill you."

Weaveworld

By [ ], Collins Weaveworld publicity, 1987

"Is there any subject I wouldn't touch? Yes, I could never set a

horror story in a concentration camp, for example. I don't believe in

trying to exploit atrocities that have truly happened, or that might

happen, like being attacked in the shower by a psycho. My duty as a

writer is to produce elaborate and entertaining metaphors for the fears

that are inseparable from the human condition. Fears of growing old,

losing loved ones, losing your faith, etc, etc. I want to stir up the

Jungian mud, enter the symbolic life that we all live between our ears.

I want to probe the dreams and nightmares we're visited by at four in

the morning. But I don't want to make people fearful of being murdered

in their beds."

Clive Barker

By Ste Dillon, extracts presented in Clive Barker's Shadows in Eden, edited by Stephen Jones (interview conducted on 27 October 1987 and intended for publication in Adventurer, but ultimately unpublished in full)

"The problem is, in a genre which is full of phallic swords and that kind of thing, it's important to establish female power and female potency, and the eroticism which comes with that. And it needn't all be 'goody-goody' stuff, I mean Immacolata particularly; she 's kind of sexy, yet dangerous at the same time. And yet a virgin, which makes her all the more sexier of course. "

Horror Lovers Are Hailing England's Clive Barker, Creator Of The Awesomely Awful Hellraiser And Weaveworld, As The New Guru Of Gore

By Peter Goddard , The Toronto Star, 31 October 1987

"I think there are places in David Cronenberg's work - work which I admire

without reservation I may say - where we see images of sexuality associated

with repulsion - in Shivers, the exchange of a monster through a lesbian

kiss for instance. I try to avoid that.

"Of course I'm writing about sexuality too, but I am also writing about the

whole spectrum of repressed ideas in our society, sexuality only being one

of them. The association of sexuality with death is an extremely potent and

dangerous idea. I try wherever I can to address dangerous ideas and make

them accessible...

"What's really important? It will be easier for you or me at a dinner party

tonight to raise the subject of stocks and shares than it will be to raise

the subject of sex and death.

"We would be thought to be cultivated individuals talking intelligently if

we talk about the stock exchange. We would be thought to be perverse,

tainted if we were to talk about our erotic dreams or about our fears and

hopes for death. There is something wrong with a society which has that

order of priorities."

In World Of Skinless Bodies, 'Weird' Means Really Macabre

By Liam Lacey, The Globe and Mail, 31 October 1987

"A lot of critics have this reaction that goes like this: 'Well, his prose

is quite good and he knows how to write. So why does he write about such

nasty stuff?' But my subject matter - eroticism and death - is something

everyone relates to. The highest praise I could have was that I'd written a

pop classic. We really don't need any more novels about adultery on campus.

"I used to feel that my fondness for junk fiction and films was a secret

vice - that I'd really rather read Stephen King than John Updike, and I'd

really rather see a Roger Corman film than a Bergman. But I came to see

that, properly shaped, the elements that drive popular entertainment can be

as profound as anything else. I'm not interested in escapist fiction, I'm

interested in fiction that uses the fantastic to be confrontational, to

help people explore the contradictory layers of their own experiences."

Clive Barker: I Am A Monster!

By Stephane Nicot, Gai Pied Hebdo, No 292, 30 October - 6 November 1987 (note: translated from French)

"I don't define myself as a horror writer. I don't define myself by my sexuality. I consider myself open. I consider myself capable of believing in infinite possibilities."

Barker: 'I Want To Continue To Surprise Myself'

By W.C. Stroby, Asbury Park Press, 1 November 1987

"Sometimes I do feel myself caught between twin pincers. On the one hand, there's the guy who thinks I'm mucking about in the shallows when I should be producing high art. On the other, there's the guy who thinks that I'm being high-handed in a genre which should essentially remain pulpy. But my whole mindset has always been to try and use popular forms and root them and make a kind of emotional sense out of them. Whether it be Hellraiser or Damnation Game or Weaveworld, the source of the material and rooting the material in some kind of social reality is only a way to let it fly into other places, other realms, other modes of thinking and being.

"I think finally what's important is that we celebrate the imaginative, we celebrate the mind's power to recreate the world, sometimes in a kind of visionary way. In the dream life of America, I think politicians and politics have a smaller part to play than Mickey Mouse, King Kong and Karloff."

Hellraiser

By Kim Newman, Sight And Sound, Vol 56, No 4, Autumn 1987 (note: portions identical to NME, 12 September 1987)

"We're telling a strong story and therefore the rococo flourishes which distract are redundant. We're not putting in point of view shots of creatures which do not exist. There are always payoffs to hints like that. We show the monsters, the horrors. That was always the thing with the short stories. We're giving the audience the goods."

Bogy Barker

By Louis B. Hobson, The Calgary Sunday Sun, 8 November 1987

"My father was an Irishman who worked on the docks. My godfather was a captain and my grandfather a ship's engineer. It is from them that I get my craving for adventure, but instead of using a ship to get to faraway places I use my imagination...

"I am currently more interested in addressing the business of transcendence and the literature of the fantastique than I am in what people might consider pure horror.

"Weaveworld is a great departure from Hellraiser and it's the direction I want to pursue. My next film as director and writer will be fantasy, not horror.

"I've done my low-budget horror film. There is no use in repeating the experience. I always believe it's best to get out while you're winning in case you can't repeat the success."

Horror Master Rejects Virtue, Victory Of Status Quo

By Ian Harris, Calgary Herald, 10 November 1987

"One of the great 19th century inventions was the notion of the artist who works purely for his or herself.

Emily Dickinson never published during her life; she gave all to the personal vision. For myself, what is spurious

about this philosophy is that you end up believing art can operate in a vacuum - separate from the communication

you're supposed to be having with an audience... If a book is written and nobody ever reads it, is it art?

"Horror is forbidden stuff; it's not polite. Horror is about the rejection of the status quo, which is

why I value a film like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre over Poltergeist because, in the end, Poltergeist is about

the virtue and victory of the status quo. What I'm saying in my fiction is that things cannot be the same once the

events of the story have occurred."

Heaven For The Hellbound

By Ian Birrell, Ham and High, 13 November 1987

"My duty as a writer is to produce elaborate and entertaining metaphors for the fears that are inseparable from the human condition, such as fears of growing old, losing loved ones or losing your faith. I want to stir up the Jungian mud and enter the symbolic life that we all live in between our ears.

"I want to probe the dreams and nightmares we are visited by at four in the morning, but I don't want to make people fearful of being murdered in their beds...

"I can never remember a time when I did not have all these thoughts and ideas. As children we are taught to shut down the parts of our minds that wander, but for some reason or other I never did."

Horror Superstar Clive Barker On Having The World By The Balls At 35

By Steve Newton, The Georgia Straight, 13 November 1987

"I think that what you're scared by in your life is generally stuff you repress. And I learned quite early on in life that I didn't really want to repress very much. I was perfectly keen to sort of let it all hang out and say, 'Yeah, I think death is really interesting, and I'd like to go to an autopsy.' "

Contemporary Authors

By [ ], 21 November 1987 (note : full text online at the Barnes & Noble site)

"So often you hear the pejoratives which are associated with this kind

of fiction, even though many of its formative artists in America and in

Britain are amongst the highest achievers. I'm thinking of Melville,

for one. Moby Dick is clearly a fantasy book. I'm thinking of Mary

Shelley's Frankenstein and Ursula Le Guin's 'Earthsea' trilogy, among

other books. These are extraordinary works. Fantasy and horror fiction

or science fiction have been written by the greats of our respective

countries. And yet, critically, this is in the latter part of the

twentieth century a despised genre, which I find discouraging.

"Part of the problem, I think, is that we are hooked on realism, hooked

on naturalism - this despite the fact that many of the great masterpieces

of world fiction are non-naturalistic. Where do we begin and where do

we end with that list? It would include many of the plays of

Shakespeare; it would include Milton and Blake and Shelley. It would

include Moby Dick and other American classics, works by Poe and

Hawthorne. It strikes me as shameful that the genre is looked down upon

now despite so many great works of the fantastique throughout literature.

I think a part of the problem is that the critics don't have a critical

vocabulary, a way to get a critical handle on this material, so they

ignore it. J. G. Ballard, who is a brilliant writer, a brilliant social

critic, and an extraordinary imaginer, wasn't recognized by British

critics as the great writer that he was until he did a work of

'autobiography', Empire of the Sun. This was after he had behind him

many books that might be very loosely termed science fiction, which

would have proved to all but the heavily blinkered that he had been

writing wonderful prose for many years. It was only when he slipped out

of the genre channel, lost the label, that the critics said, 'My God!

This guy can write!

"It's a shame. But they say that success is the best revenge, and the

fact is that fiction of this kind is now one of the cornerstones of any

best-seller list. In one very real sense it's a genre like romance,

like the thriller, which doesn't need critical approbation to make it

successful."

Horrorstar Rising

By Michael Mirolla, The Gazette, Montreal, 28 November 1987

"There's more to the world than the salesman's pitch. The universe is steeped in the metaphysical, the spiritual, the moral... Horror, fantasy, mainstream - those are all salesmen's terms. They're just a way of categorising books in order to sell them.

"It's the imagination that counts and what comes out of it. As for the rest... well, I'm glad they've labelled Weaveworld as fantasy because it doesn't have that gut horror feeling to it - despite some pretty terrifying images - but that's as far as it goes....

"Part of what I was trying to do in Weaveworld was to recreate some of the magic we seem to have lost, to recapture some of the awareness of the world around us that either through complacency or uncaring we've let slip away."

The Author Of Blood

By David J Howe, Starburst Winter Special 1987/88

"In movies, I've always had a passion for film noir, and that reflects itself to some extent in my work. There are an awful lot of gangsters, whores, pimps, hustlers and druggies wandering around my stories and in some cases, like in 'The Damnation Game', even being the heroes and heroines of the story. The other thing that I get from film noir is the element of mystery. A lot of my stories have some kind of puzzle element in them. A sense that something has got to be unravelled and eventually be made understandable. Sometimes that can be a literal puzzle, as in 'Hellraiser', and in my new novel, 'Weaveworld', there is a country woven into a carpet which is another sort of puzzle."

The British Invasion: Clive Barker

By Nancy & Robert T. Garcia, American Fantasy, Winter 1987 (note: interview took place in 1986)

"I think that the difference [between the first 3 Books of Blood and the second] to a

great extent is that I wrote a novel in between. I wrote The Damnation Game and I think

that actually makes a huge difference. You know I'd never published anything before ever;

before the Books of Blood. Never even been in magazines, nothing. So I did these things

and they finally published them and they were very successful.

"Then I did The Damnation Game which is a whole different experience. It's a big

emotional experience in the way that a novella never can be. And then when you get back

into the novellas they are enriched, I think. More human maybe, more confident maybe. I

don't feel the need to go 'Whooo' every time. I can lay back a little bit. It's

interesting, you win some, you lose some, because there are some people who prefer the

first three. I prefer the books the older they get, as it were, so that by the time I

get to Volume Six I'm very, very happy indeed.

"But I'm always very anxious about the work and I'm critical of myself. You know there

are places where I look back over the first three books and think, 'Oh, I could have

done that better,' or, 'Why did I ever do that?' but I suppose it would be horribly

smug of me if I didn't."

Hellraiser

By Stephen Jones, American Fantasy, Winter 1987

[re Frank's resurrection] "I think the imagery will be very strange. It will be spooky. It will be very physical and very graphic. Although it doesn't begin the film, it does begin the supernatural events in Hellraiser."

Weaveword

By Brigid Cherry, Brian Robb, Andrew Wilson, Nexus, No 4, Nov-Dec 1987

"There are worlds within worlds within worlds in Weaveworld. One of the characters enters a book within a book, there to discover that she's in that ultimate wild wood of all fairy tales. She doesn't know whether she's the dragon or the maiden. The villain turns out not to know whether he's the dragon, the maiden or the knight."

What Scares Clive Barker

By Thane Burnett, The Daily News, 6 November 1987 *

"When my first book came out, if I fell flat on my face, no-one but my publisher and I would have known. Now, everyone will know. And there are some people out there who would like to see it happen. The fact that the carpet can be pulled out at any time makes it nerve-wracking. But I couldn't stop [scaring people]. It's what I'll keep doing if I should fall on my face. It's what I'll do in the afterlife."

The Great Life

By George Christie, The Hollywood Reporter, 17 November 1987

"I guess I had an unusual childhood in that I hated toys, all I wanted was whatever had to do with painting."

Clive Barker 'Innerview'

By Steven Neal Shaffer, New Blood, 1987 (Note: interview took place at November 1987 signing at Change of Hobbit, Santa Monica)

"Fame is like flying. On the ground and looking up it appears exciting

and romantic. Once in the air it's all bad food, stale air and turbulence."

Raising Hell With Clive Barker

By Douglas E. Winter,

(i) Rod Serling's The Twilight Zone Magazine, Vol 7, No 5, December 1987

(ii) Clive Barker's Shadows in Eden

"Writing is quite a solitary experience. But it gives you absolute and complete power. Whatever your pen desires to create is created. Nobody questions it, nobody challenges it, nobody tries to better it. Nobody puts pressure on you to weaken or dilute it. However, you do this in splendid isolation."

Hellraiser

By Alain Charlot and Marc Toullec,

(i) Impact, No 12, December 1987

(ii) Mad Movies 50 Ans, Hors-Serie No 69, November 2022 (Note: translated from French)

"I am afraid, for example, when I am in the hands of someone who could do anything. When I saw The Exorcist for the first time, I did not know William Friedkin, but I thought 'This guy can do anything.' You are at the mercy of a madman. I like that."

* Quote taken from extracts presented in Clive Barker's Shadows In Eden, edited by Stephen Jones - full text wanted.

Click here for Interviews 1988...