Interviews 1988 (Part One)

...'88 saw Clive fulfilling promotional requirements for both the previous year's publications - Weaveworld and (in the US) The Damnation Game; but in the meantime there were also more immediate projects afoot. January saw Hellbound being shot at Pinewood and Hellraiser winning, the following month, the Grand Prix de la Section Peur at Avoriaz. Whilst Hellbound was in post-production, Underworld was revealed to an unsuspecting video audience and Clive found time to work on Cabal. By the time Hellbound saw the light of day, Atkins was already writing drafts for Hellraiser III, while Clive had moved on to the Tapping the Vein series for Eclipse; Rawhead Rex & The Yattering & Jack for Arcane and Epic's Hellraiser. Halloween brought with it the role of MC at the World Fantasy Convention in London, although Clive thankfully warded off Stephen Laws' attempts at strangulation... By the end of the year Clive was fielding questions on the film so full of promise and so close to his heart - Nightbreed, as well as presaging the appearance of The Great and Secret Show the following year ...

BBC Schools' Broadcast

TV interview by [ ], BBC TV Schools' Broadcasting, 1988 *

"Try and find those stories or those ideas that belong specifically to yourself. Don't be scared of finding new areas, new ideas - new ideas are important, and there's no value in simply rewriting what you've read elsewhere."

Film '88

TV interview by [Barry Norman], BBC Film '88, 1988 *

"I have yet to meet in a signing a fan of mine who seemed to be anything but a well-balanced individual who was having a good time using their imagination to the limit."

Can We Talk?

Transcript of a radio discussion between Harlan Ellison and Clive Barker, KPFY, Los Angeles, 1988. Reprinted in Midnight Graffitti Special No 1, Winter 1994/95

"There's a lot of sex in my books, there's a lot more sex in my books than there is in

most horror fiction. Horror fiction tends to be quite a puritanical area. One of

things people say is, 'Why do you do this stuff?' And I have said, there is a lot of

very horrific elements to sex, which has seemed to be almost like I've passed wind in

public or spat into my soup. People are looking at me as if to say, 'What? You think

there is something horrific about sex?' As though sex is sanctified...

"And yet there's also a thing where the imagery of the very religions, the very temples

in which they worship, is informed thoroughly with sexual imagery. And one has constant

references to flesh and the mysteries of the flesh. And it seems to me that every time

you talk about the transcendence of flesh, you're talking about the flesh! You're back

to the problem, guys!"

Horrific Success Of Writer Clive

By John Slim, Evening Mail, Birmingham, 2 January 1988

"The trigger was birth. I have always been into this sort of thing. I have always been into, not necessarily horror stuff, but always into fantastical fiction of some kind or another. It's always been the imaginative which has drawn me. I can never imagine writing a realistic novel or making a realistic movie...

"Here is a book [Weaveworld] in which for the first time there is some considerable and serious eroticism at work in the fantasy. When the monsters appear, they're very dark and very strange, but finally the most important thing about this is that it's a book which, instead of just being another surreal fantasy, treats seriously the question of why we need fantasy in our lives. Why do we dream? Why do our imaginations work in that way?"

Clive Barker

By Michael Flores, (i) It's Only A Movie, 1988 (ii) It's Only A Movie, Best Of No 2 - The Interviews, 1989

"When I was a kid I didn't have access to EC comics. We didn't have the Twilight Zone on television. I saw that

It's Only A Movie, Best of No 2, 1989

much, much later. There were no movies, very few comic strips and no television. It was there to be had, but my parents wouldn't let me have it. When I could get hold of it I'd read Poe, Bradbury - and I do love the pulp-like horror comics, but I didn't see them growing up.

"My childhood imaginings fed upon themselves. My formative years were spent with my own imagination. At the time it was deeply frustrating, but now I see it as a blessing in disguise."

Clive Barker: Thinking Man's Horror

By Caroline White, Higher Ground, 1988

"My books are all fantastic in some way or other, they'll blow reality to fuck. It can be quite subversive at its best and that's one of the reasons I think it's treated with such contempt critically.

"To people who don't know or like the genre they talk of horror fiction as if it were a one-pony town. It isn't, there's an awful lot you can do with the genre. There's a world of difference between Peter Straub and Stephen King, between James Herbert and Ramsey Campbell, between stories that I write within my own area, or between somebody who likes to write about very visceral or physical stuff, and people who like to write subtle, psychological stuff. It's only the genre's detractors that insist on seeing it as a very narrow area. Part of the glory of fantasy writing seems to me to be its depth. You know, it runs all the way from Moby Dick to Alice in Wonderland...

"The best thing I think to do is to go into whatever your imagination is up to at any particular time, and put it down in the most literate fashion you can... I have a lot of strong supporters, but I have a lot of detractors as well, a lot of people who just don't like horror fiction, and don't like the subject matter of horror fiction which is death, obsession, madness, strange sexuality, cults, etc. and, as far as I'm concerned, that's what life's all about."

Horrors!

By Anand Banerjee, The Peak, 28 January 1988

"The sexual has been missing from horror fiction for such a long time, and the explicitly sexual almost missing entirely; and yet the sexual perspective has been so much an important part of what underpins horror fiction. When Dracula bites the neck of the female victim and she collapses in his arms, he is bringing her death and orgasm at the same moment. The correlation between the two is to some extent related to our physicality. We're talking here about the big problem facing the physical animal that we are: being alive and vulnerable and moved by experiences over which we have little control. We have no control over death; little control over arousal. Both are fundamentally associated with our bodies.

"The idea that somehow or other lust, sexuality and love are a way of keeping death at bay and sweetened - or at least made bittersweet or more potent - by the fact of death, is a paradox. It would be difficult to imagine a world in which there was no death, and in which love existed. We are in love with what must die because everything dies. And we value things all the more because we fear we'll lose them. That's true even of ourselves."

Weaveword

By Brigid Cherry, Brian Robb, Andrew Wilson, Nexus, No 5, January-February 1988

"I don't really enjoy straightforward Sword and Sorcery books - that's not to put them down at all. I'm really interested in stories

which take you from the real world, that is the world that we apparently live in, to other places. In children's literature that would

be Peter Pan, Alice in Wonderland, Narnia, for instance. Alan Garner's Elidor is a fabulous example of that. What's interesting

about those kind of structures is that they actually take the protagonist, who begins in a conventional household of one kind or

another, with their problems and their anxieties and their condition as children, into this other world; into Never-Never Land, into

Narnia and so on, where there are adventures and events which make them reflect upon themselves and they come back

changed as a consequence of it. Now that's much more interesting than just entering Middle-Earth on page one because that

seems to me to be suspiciously close to escape. If you actually enter a book on page one and you're immediately in a world

whose values don't reflect the values of the world out of which you've come, in which heroism is relatively easy and in which the

notion of good and bad is very clear, then it's very difficult to come out of such a fiction at the other end with a sense of how you

use the information that you've got from the book in your life. I happen to think, talking about fantasy and confrontation, that the

best fantasy arms and heals. It arms you for the problems and it heals you as well."

be Peter Pan, Alice in Wonderland, Narnia, for instance. Alan Garner's Elidor is a fabulous example of that. What's interesting

about those kind of structures is that they actually take the protagonist, who begins in a conventional household of one kind or

another, with their problems and their anxieties and their condition as children, into this other world; into Never-Never Land, into

Narnia and so on, where there are adventures and events which make them reflect upon themselves and they come back

changed as a consequence of it. Now that's much more interesting than just entering Middle-Earth on page one because that

seems to me to be suspiciously close to escape. If you actually enter a book on page one and you're immediately in a world

whose values don't reflect the values of the world out of which you've come, in which heroism is relatively easy and in which the

notion of good and bad is very clear, then it's very difficult to come out of such a fiction at the other end with a sense of how you

use the information that you've got from the book in your life. I happen to think, talking about fantasy and confrontation, that the

best fantasy arms and heals. It arms you for the problems and it heals you as well."

Clive Barker : The Horror !

By Morgan Gerard, Graffiti, Vol 4, No 1, January 1988

"I don't want sanity if sanity is what comes out of the television. I don't want sanity if sanity is a world without miracles, a world

without the possibility of transformations. I don't want sanity if sanity is politics and economics and mortgages and learning to

live with the neighbors...

without the possibility of transformations. I don't want sanity if sanity is politics and economics and mortgages and learning to

live with the neighbors...

"The place between the dream and reality, particularly if you've been working on a book for so long, becomes so thin. You start

to dream the characters. You have conversations with them, you fuck with them, it's intimate. I also had this fabulous dream

about Tina Turner. I don't drive so I don't know what this means. I was in a very low-slung car and she was in the passenger seat

and I was driving and I can't drive and she was stark naked! We were driving at an immense speed down the freeway in the wrong

direction and these humungous trucks were coming toward us - and then, as we were beneath the trucks, she would arch her

body up so as to make contact with the undercarriage of the trucks and these sparks were flying! It was very sexy, very strange."

Hair-Raiser

By Phil Edwards, Crimson Celluloid, No 1, 1988

[Re: praise from Stephen King] "It comes from a master of the genre and

somebody who, in very real terms, has made the genre 'box office'. In

literary terms he has made it an acceptable 'read'.

You get onto the underground and see lots of people reading Stephen

King in a way that twenty years ago you wouldn't have seen them reading

Dennis Wheatley. It's now an acceptable thing to do, I think it's great

that horror fiction is no longer some sort of a secret society!

"He's made it acceptable to people who once would have said, 'I

reject horror stories'; or 'I don't like horror stories'. I'm sure

there were people who went to see 'Carrie' who had never been to see a

horror movie before. There are, I'm sure, people who read his books

who don't read any other horror fiction. He has become a household

name and I think that horror has gone into the household on his

coat-tails, as it were.

"So when he says what he did about my work, there's a mammoth

responsibility that goes with that; one which would be irksome if I

didn't believe he were always going to be the master. I really think

he's always going to be the guy who gets to people. I think my stuff

is too weird to ever work with the supermarket crowd."

Interview : Clive Barker

By Gero Reimann, Winifried Czech and Norbert Tass, Phantastiche Zeiten, February 1988 (Note - translated from the German)

"I had written two screenplays that were totally massacred. The people

were opportunists. One director was responsible for both of these

outrages - a man called George Pavlou. Not a bad person, but not a

good director. Unfortunately, horror films make money - and

frequently-playing horror films a great deal of money, without anyone

taking the trouble to make a good movie.

"I do love horror films and horror literature. I love Cronenburg,

Lynch, some of Wes Craven, much of Brian de Palma. But it is mightily

disappointing when one writes a good screenplay and then is obliged to

go along with all the modifications."

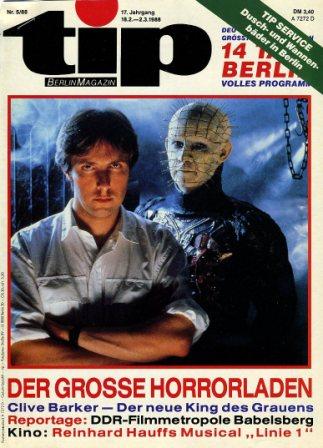

Der Grosse Horrorladen

By Karin Aderhold, (i) TIP, No 5, 18 February to 2 March 1988 (ii) TIP Filmjahrbuch, No 4, October 1988 (note - translated from the German)

[Why is erotic literature so dangerous?] "To me, it appears to be connected with the fact that sexuality is an area in which we lose and give up any control. By their nature the people in governments are control freaks. People who go into positions of power are control freaks, otherwise why they would look for power? Don't tell me that it is to do with the fact that they worry themselves about the welfare of our souls. Plato says in his writings about the state, that for an absolutely stable, perfect government, first the poets must be exterminated. What kind of power must poems have then! Also the ruling powers of the Third Reich said we must rid ourselves of these degenerate artists. Art is dangerous for a state, and art which concerns itself with taboo topics such as sex and death, is doubly dangerous. I mean, Steven Spielberg is naturally a danger for nobody. Plato would have probably said that he could stay."

Interview : Meet Clive Barker

By Sheryl Weilgosh, Castle Rock, Vol 4, No 2, February 1988

"I enjoy the emotional commitment that you get with the characters [writing a novel], which 'Weaveworld' was. A nine-month commitment to characters. I enjoy that. I laugh with them, I cry with them. It's much more difficult to have that kind of commitment over the shorter period of even a novella. I think there will be more novels, at least for the foreseeable future."

Le Regne De L'Enfer

By Guiseppe Salza, L'Ecran Fantastique, No 89, February 1988 (Note - translated from the French)

"I started, at a very young age, as a designer for underground

magazines and things like that. And then I began to illustrate some

book covers. I drew those for my Books Of Blood myself. From there, it

was a natural progression to creating images on screen. Consequently,

I had occasion to design many monsters. Everything becomes easier once

you give it an appearance.

"I wanted to create - and I feel we have reached that point - a film

which terrifies without compromise. I don't think that that's too

ironic. There is a tradition of making horror films half comic.

Hellraiser isn't like that. There are one or two laughs, but it's a

different sort of laugh. Not like in 'House'. If there is comedy in

this film it's very black comedy. But the smiles and winks in this

film are not gratuitous; I find them perfectly justified. Besides, to

make a film, you need to believe in it. I think, and this is very

important, that we have succeeded in creating horrific images which

are radically original. My monsters, the Cenobites, have nothing in

common with any of the creatures you could have seen on film before

now. We have brought a new life... a new death to this film!"

Hellraisers

By Mikal Gilmore, Rolling Stone, No 519, 11 February 1988

"One of the things that Alan [Moore] and I have in common is a kind of social contexting. The distress that we feel about the status quo, about the current English cultural condition, finds its way into the fiction. It's interesting that Alan, in Watchmen, has found a way to talk about American society which seems to be extremely potent. But he brings to bear a lot of insights which are based upon living in Britain in the 1980's, such as a sense that things could fall apart at any moment."

Im Würgriff Der Zombies

By Klaus Habricht, Tempo, No 3, March 1988 (note - translated from the German)

"Horror literature is usually reactionary and bourgeois. The strange monster is blown up into the air, the vampire has a stake driven through his chest and everything in our small-minded world is back to normal. That doesn't work for me. For me, man must learn to live with the monster."

Hellraiser

By Paul Ives, Screens, No 11, March 1988

"Hellbound is a genuine sequel. It carries on from where Hellraiser

left off. There has to be continuity of style and character. The

second picture is built upon the first.

"It's not like House 1 and House 2, which didn't resemble each other at

all. Hellbound answers the questions left by Hellraiser. You get to

learn more about the Cenobites. You get to see them being born, if

that's the right way to describe it. We go into Hell, and see

mysteries that were hinted at in Hellraiser.

"I hope there could be more films based around Hellraiser. If there

are things there to be answered you have the option to do more.

"I've got a story planned for a third film, but nothing beyond that.

Number four would have to be done without me, I think."

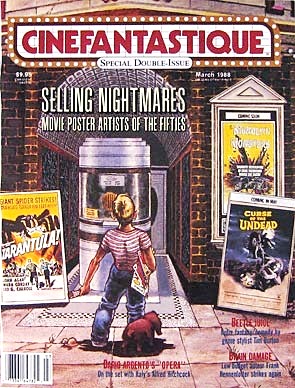

Hellraiser 2: Hellbound, Sequel In New World's Pact With Clive Barker

By Gary Kimber, Cinefantastique, Vol. 18 Nos. 2 and 3, March 1988

"The Cenobites will be back, including new ones. We are going to learn how they get made.

There is a lot of really weird stuff, even by my standards"

"The Cenobites will be back, including new ones. We are going to learn how they get made.

There is a lot of really weird stuff, even by my standards"

Clive Barker On Hellraiser, His Genre Roots And The Therapeutic Value Of Horror

By Dann Gire, Cinefantastique, Vol. 18 Nos. 2 and 3, March 1988

"Quite clearly, when you see Stuart Gordon’s Re-Animator or From Beyomd, this is not Terence Fisher’s

sensibility at work. This is something different. Fifty years from now, these pictures will stand the

test of time because they hit a moment. They have a kind of malicious energy which I adore, a

kind of punk sensibility which I adore. Subversion is in the air, subversion of values and ideas.

"The old tradition of picking up the crucifix and keeping the beast at bay with the symbol of a dead theology

is never going to work in his [Gordon’s] pictures anymore than in mine. The old values have been thrown over

in favour of something tough and unforgiving. I like that. I think that’s very modern."

APB Interview

TV interview by [ ], APB, Border TV, 6 March 1988 *

"I would not like to think that we should be guided by spurious ideas about what good taste is. At the same time, I don't want anybody to simply say it's just there for the sake of it. There wasn't anything in Hellraiser that was there just for the cheap sensation of it... The BBFC, who are the censorship body here in England, are immensely responsible and responsive. They took only four seconds out of Hellraiser for the video, which I think is really nothing. It's immensely sensitive of them."

Terror Tactics

By John Brosnan,

(i) Time Out, 16-28 March 1988

(ii) Clive Barker's Shadows in Eden

"The whole structure of a novel like 'The Influence' or my 'The Damnation Game' has at its centre the supernatural MacGuffin. Now supposing the mainstream reviewer says, 'Well the problem is that the very introduction of a supernatural dimension undercuts the reality of what you've created.' But I think what mainstream critics have fallen prey to over and over again is a limited sense of reality. Herbert Reed, in an introduction to one of his books, said that reality is a bourgeois prejudice - I love that! I think it's also a critical prejudice. By introducing the elements of the fantastic we invalidate our connection with the reality in which the critic lives."

The Hell It Is

By Peter Hogan, Melody Maker, 19 March 1988

"The ego is satisfied by the books; the extrovert nature is satisfied by the movies. Finally, I expect to be judged by the books - for better or worse, they're 100% me."

Beyond The Limits

Hellbound set visit by John Gullidge and John Martin, Samhain, No 8, March/April 1988

"I always knew Kirsty would go into Hell for her father, but the question was whether she would find him when she got there."

(Hell) Bound For Glory

By Stefan Jaworzyn, Shock Xpress, Vol 2, No 3, Spring 1988

"I was talking to an Australian interviewer and told him we were killing off the Cenobites. He said, 'So there's not going to be a third picture?' I realised that people get hooked on certain images and ideas. My feeling is, all the better to kill them off then..."

The Two Faces Of Clive

By Tim Blanks, Toronto Life Fashion, Spring 1988

"Fantasy should be confrontational - it should make us scrutinise the value of our own reality.

I'm most excited when people say about my writing, 'That started me thinking about myself...'

"I write fiction about appetite for transcendence of various kinds. My fiction is a celebration.

What critics haven't realised is I'm writing stories with happy endings."

A Hell Of A Day

By Richard Mansfield, Video - The Magazine, April 1988

"What I like to write is 'iceberg' literature. Most of it is below the surface, and you produce things that don't explain everything. There should

always be an element of mystery, places to go - very exciting places...

"I wanted Hellraiser to be as weird as it was scary... I wanted to introduce potent rather than disgusting images. My biggest surprise was

the public's reaction to the Cenobites, especially Pinhead who may have started a cult in America! We went against the horror grain by having

the Cenobites moving slowly, priest-like. They're not just fast-talking Freddy Kreuger clones, they're very serious. Their idea of a joke is,

'No tears please, it's a waste of good suffering'! They and the picture have a very black and bizarre sense of humour.

"Horror pictures at their best mix comedy and scares in a unity. They don't detract from each other. Hellraiser has no unintentional laughs.

The critics, though, are short of irony; they don't see that there are intentional jokes. They assume it's an error of judgement."

The Face Of Horror : An Evening With Clive Barker

By Joan C. Schramm, House Carfax (i) No 1, Spring 1988 (ii) No 6, Fall 1990

"I'm intimidated by Ray Bradbury and Herman Melville. But it's okay to be intimidated. Just use it to inspire yourself to do something uniquely your own and call it your own."

Clive Barker : An Eye To The Future

By Stephen Jones, Locus, Vol.21:4 No 327, April 1988

"The first film [Hellraiser] was a teaser; there were many things in there that we never got around to do with the slightly higher budget and our experience on the first film allowed us to develop the mythology. This time we're opening up the story. We are seeing Leviathan, the great Lament Configuration; we travel to the Hell from which the Cenobites were raised, and we've even got a how-to-make-a-Cenobite sequence!"

Monsters Have Brain As Well As Brawn

By David Frith, Sydney Morning Herald, 11 April 1988

"I think it's important that we continue to deal with taboo material,

because after all, that's what horror fiction is so often about. The moment

at which we get bullied into cleaning up our act is the time we cease to do

what the genre is dealing with: forbidden subject matter - death, sexual

possession, insanity and so on.

"I wanted Frank to be

able to talk about his ambitions and desires, because I think what the

monsters have to say for themselves is every bit as interesting as what the

human beings have to say... to deny the creatures as individuals the right

to speak, to actually state their case, is perverse."

Triple Threat

By Steve Niles, Greed, No 5, Second Quarter 1988

"I have to draw; I have to draw the same way I have to write. But it becomes a function of working in another medium. Many of the drawings are purely for myself as an aid to invention."

L'Enfer Du Decor

By Marcel Burel, Impact, No 14, April 1988 (Note - translated from the French)

"I am the executive producer and I wrote the story, so I watch over the

project very closely. We've drawn lots of storyboards and everything

has been discussed with Tony Randel, the director, and Peter Atkins,

the screenwriter, who is one of my oldest friends - since we were

seventeen. We've worked closely on the script.

"It is important that new people have their contribution, that we are

all at one right from the start, so as not to completely change what

has gone before. With Hellraiser, we have a whole new mythology, and

this investigation of it will uncover many surprises."

Go Straight To Hell

By Edwin Pouncey,

(i) New Musical Express, 2 April 1988

(ii) Clive Barker's Shadows in Eden

"I would like to think we could carry on the plot, picking up the momentum of Hellraiser I into Hellraiser II and then pick up the end of this one and get into Hellraiser III. In principle you could take the title sequences off II and III and show four and a half hours of relentless horror movie. That's a dream."

PN Reports

By [ ], Publishing News, 29 April 1988

"Whereas in the Books of Blood and Hellraiser I took readers on a journey to hell, in Weaveworld we  take a trip to heaven. But as there were glimpses of heaven on the way to hell, so there are glimpses of hell on the way to heaven.

take a trip to heaven. But as there were glimpses of heaven on the way to hell, so there are glimpses of hell on the way to heaven.

"There is, though, an overall feeling in Weaveworld that you are moving towards goodness and redemption which is not something you could say about my previous work...

"I suppose you could say that I have been fascinated in carpets since the age of two when I started to crawl on them! But I have always loved them as objects and the idea of finding a fantasy world in a carpet and using it as a subject for a book has been in my mind for some time.

"Even my previous books, for all their bloodletting, were in many ways puzzle-related and I have always thought that a carpet, with its patterns and weaves, [is] a legitimate hiding place."

Knocking On The Glass : The Mind's Menagerie And Other Conceits

By Clive Barker and Peter Atkins,

(i) Time Out, 1-8 June 1988 (EDITED, as 'Hell Raisers')

(ii) Clive Barker's Shadows In Eden

"In our fictions, in our work on the screen or the page, what we, and others like us, are doing is denying - not Reality - but the notion of a single definition of the Real... We use Art as windows through which to glimpse the miraculous. And some works of art are great big Rose Windows, and some are basically just chinks in the wall... but even the smallest chink is to be celebrated, particularly in this modern world which, more than ever before, forces a limiting version of Reality at us."

Beneath The Blanket Of Banality

By Lionel Gracy-Whitman & Don Melia,

(i) Heartbreak Hotel, No 4, July/August 1988

(ii) Clive Barker's Shadows in Eden

"If we need a thumbnail sketch of what evil is, we just have to look at any system which is in love with the eradication of the imaginative moment - and for imaginative moment, read people who embody creativity: the artist, the poets, the lovers. The Third Reich is the perfect example of this. Any system which wants to eradicate the folks who don't fit, won't fit."

Hellbound - On The Set Of Hellraiser II

By Alan Jones, Starburst, No 119, July 1988

"'Hellbound' is pretty fast off the ground, even considering recent sequelitis in the genre. But at the moment there seems to thankfully be a huge appetite for anything my name appears on. Weaveworld has been on every major best-selling book list - 17 weeks in Canada alone - and it surprised me by doing better than The Damnation Game. So why not strike while the iron is hot?"

Clive Barker

By Richo and Pigswill, Grim Humour, No 12, Mid 1988

"Even back when I was beginning The Books Of Blood and whatever, I never actually devoted certain periods of time to any one thing. All of the Books Of Blood, The Damnation Game and Weaveworld were written side by side with other things I was doing at the time. Weaveworld was actually written at the same time that we were doing Hellraiser... I'm not emotionally cut out for doing just one thing. Curiously, it seems to give me a much better creative power when I'm doing several things at the same time. Y'know, at the moment I'll spend my morning at my desk, spend the afternoon here [Pinewood], filming and then spend the evening with some other project. I've always worked on the basis that I could do so many things at the same time."

* Quote taken from extracts presented in Clive Barker's Shadows In Eden, edited by Stephen Jones - full text wanted.

Click here for Interviews 1988 (Part Two)...