Evolution Of A Character - Pinhead

Early Incarnations

Phil and Sarah Stokes: "In 1973, the same year in which an unknown Clive Barker directed a small group of his schoolfriends in

his 8mm movie version of Salomé, he also directed the group in Hunters in the Snow, an original play with Doug Bradley in the role of

the Dutchman, an undead inquisitor and torturer. Acknowledged by both Barker and Bradley as the earliest incarnation of Hellraiser's

Pinhead, his bleakly eloquent delivery now seems strangely prescient:

'Why do you murmur? Why do you dread the calm symmetry of death? Is there not succour to be drawn from oblivion? The pattern

must be complete. Birth is but the first preparation for death.'"

The Marriage Of Heaven And Hell: Demons To Some, Angels To Others

Anchor Bay Hellraiser DVD Box Set Liner Notes by Phil and Sarah Stokes, July 2004

Doug Bradley: "The character I played in Hunters, the Dutchman, I can see echoes of later... Pinhead in Hellraiser. This strange, strange character whose head was kind of empty but who conveyed all kinds of things. I remember getting the best note ever from a director when I was the Dutchman; Clive said, 'Dougie, I want you to say this line as if the North Wind was blowing through your eyes...'"

A Dog's Tale

By Peter Atkins, Shadows In Eden, 1991

Celluloid Images - The Forbidden

"Like a psychic's production of automatic writing, the work we create when we are young can be a powerful clue to what obsesses us.

In a trance of innocence, without the demands of commerce or self-consciousness, we speak with a purity that is difficult to achieve in

later work. Not that purity is necessarily a great artistic virtue - some of the most boring art I know values that quality far too highly -

but in the scrawl of an unwitting mind there may he interesting codes to be broken.

"I offer this observation in relation to the release on video of two short films I made some 20 years ago, Salomé and The Forbidden.

The former was made on eight millimetre, the latter on 16 millimetre; both were shot in black and white (The Forbidden is in negative

throughout). Neither have dialogue, but 'mood music' has been added for the video release, which effectively supports the hallucinatory

atmosphere of the pieces.

"In short, they are technically extremely crude and their story-lines obscure: Salomé vaguely follows the biblical tale of lust, dance,

martyrdom and murder, but only vaguely; The Forbidden, though derived from the Faust story, is steeped in a delirium all of its own.

Notwithstanding, the images still carry a measure of raw power some two decades on, in part perhaps because the context is

otherwise so unsophisticated...

"I was surrounded by friends who shared my enthusiasms, among them Doug Bradley, who went on to become Pinhead in the

Hellraiser films, and Pete Atkins, who penned the second, third and fourth instalments in that series. They were tireless and brave

collaborators. Encouraged by the sexual freedom of many of the underground films we saw, we put propriety aside and followed our

instincts. Flesh, which is so much a part of the stories I have told in the years since, is given a fine showing in these pieces,

particularly in The Forbidden. As are images of anxiety and death. The head of John the Baptist, lopped off and presented to Salomé

for kissing; the body of Faust, laid out on a table by angelic presences and elegantly skinned; a man dressed as a demon moving

through a negated landscape; another demon, naked and blank-faced, whirling in a dervish frenzy.

"Some of the images - a board of geometrically arranged nails, a figure out of Vesalius, skinless but perfectly calm - find new forms in

later films. In this sense these brief works are sketches for far more elaborate renderings, and both films might be mined for such

prefigurings. But they would not, I think, do them great service. Yes, they are certainly scrawls - unkempt and unproficient but there is

a hermetic quality in them both that I almost envy."

Trance Of Innocence

Essay on his early films by Clive Barker, Sight and Sound, Vol 5 No 12, December 1995

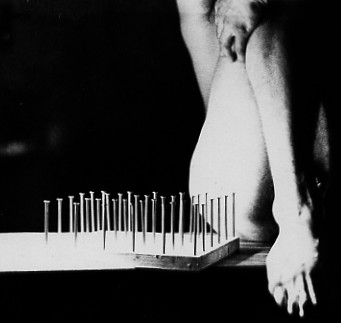

The nailboard as seen in negative on screen in The Forbidden, 1975-78

Previously unpublished photo from Clive's archive. Experimenting with shadows thrown by the nailboard, around 1975

Doug Bradley: "One image I remember very strongly from The Forbidden was that Clive had built what he called his 'nail-board' which was basically a block of wood which he'd squared off and then he'd banged six-inch nails in at the intersections of the squares. He spent endless hours playing with what happened if a light was swung around in front of it to see the way that the shadows of the nails moved and what happened if it was top lit and so forth. Of course, when I saw the first illustrations for this gentleman, it rang a bell with me that here was actually Clive putting the ideas that he'd been playing around with with the nail-board in The Forbidden, now 10, 15 years later or whatever here he'd now put the image all over a human being's face. Which is typical of the way that he will work with ideas, you'll find little bits of ideas that he would play around with that ten, fifteen years later when apparently it's all forgotten with, that idea is suddenly brought up again and dealt with in a much bigger way."

Salome and The Forbidden video release

Interview on the Redemption video, 1995

Doug Bradley: "It wasn't a great surprise to me when Pinhead appeared and I saw the first sketches, I made that association straight away. It was no surprise to me that Clive, having created this nailboard thing, would then want to go the next stage and animate it - that's typical of him. It's a weird thing to do but the fact that we're standing here with a mass-produced face proves how much it grabbed everyone's imaginations."

Maximum Exposure

Interview on Sci Fi Channel show Maximum Exposure, 2000

Celluloid Images - Underworld

The Forbidden, shot over an extended period between 1975 and 1978, lay unedited until the early 1990's when the UK's South Bank Show producers asked Barker's permission to edit it together. Meanwhile, Barker continued to write theatre scripts and began, in the early 1980's to turn his hand to the short stories that would make his name.In the midst of writing these stories, he met George Pavlou, an aspiring feature film maker and, in 1982, Barker wrote a treatment for a movie called Underworld that pitted gangsters versus mutants in a collision of film noir and fantasy. The project was not, however, greenlit until late in 1984 with a January 1985 start date for principal photography. This necessitated Barker breaking away from writing The Damnation Game to turn the two-year-old treatment into a screenplay. The 1982 treatment had simply had Doctor Savary die of a gunshot wound at the hands of Motherskille, but the screenplay envisaged an intriguingly different demise for Denholm Elliot's character... Unlike much of Barker's screenplay (which was extensively rewritten for the shooting script by James Caplan), this scene was indeed filmed, but ended on the cutting room floor...

"I thought it would be really great to have guys in really nice three-piece suits packing Uzis up against creatures from the depths who happen to be malformed only because they were using a drug which these gangs have put out in the first place. Their dreams were manifesting themselves as physical things, so I wanted real surrealism. I wanted a guy who dreamed he was a tree and was growing into a tree, all kinds of weird stuff... I finished the screenplay; they said it needed tits and car chases. I did one rewrite, then they took it off me and they wrote in tits and car chases. There were seven of my lines left; they even killed different people. One thing I'm proud of - I plot well, I plot tightly. If a character appears on page three he has a purpose on page ninety-three, otherwise he isn't on page three. So it's really irritating when they kill a different villain. I had a great scene where the villain of the piece has these dreams and nightmares manifest themselves through him physically. He was forced by the monsters to take some of his own drug - he was a doctor, and all the way through we'd seen him using hypodermics on people. These pricks appeared on his face one by one and hypodermics pushed through so his face became a mass of needles - an image I finally used in Hellraiser, of course."

Weaveword

By Brigid Cherry, Brian Robb and Andrew Wilson, Nexus, No 4, November-December 1987

93 INT. DERELICT HOUSE

Savary is backing towards the rear of the house.

SAVARY : Nicole - come to me.

Nicole hesitates.

SAVARY : Come!

Nicole moves at last. But there is something different about her. She looks lovely - more beautiful than we have seen her

before. She advances towards Savary, hands outstretched. She seems to be glowing. Savary is puzzled.

NICOLE : I know why the drug doesn't harm me. I'm a Dream Maker.

Nicole gently touches Savary's hand.

NICOLE : It gives me power. Making the dream flesh.

Nicole gently strokes Savary's hand.

NICOLE : (hypnotically)I can shape your dreams. They will live...

SAVARY : What are you doing?

Nicole continues to stroke Savary's hand. Savary is rooted to the spot. His face and hands begin to pucker and bulge.

The flesh strains upwards. Suddenly needles burst through his skin. Savary is a human porcupine with syringes for quills.

Underworld: Draft - January 1985

Filmed but unused scene from Underworld, 1985

On The Page

Citing his dissatisfaction with both Underworld and his experience later in 1985 as he worked on the screenplay for 1986's Rawhead Rex, Barker determined that he should try his own hand at the business of movie-making, drawing on his 8mm and 16mm early experiments and his experience of writing and directing for the theatre. Thinking ahead to potential stories that could become modestly-financed movies, Barker incorporated the theme of bodily disfigurement into a novella called The Hellbound Heart, written in 1985 and first published by Dark Harvest in the Night Visions anthology series in 1986."They were making these movies promising me the world and delivering nothing. They were cutting the scripts left, right and centre. Everything that could have been wrong with the way that they handled the stuff was wrong. Later on I discovered that the producers, one of the producers in particular, thought that the stuff I had written was just sick and depraved. They basically scorned the whole idea of even being in business with me. They just didn't get the movies. They didn't understand the point I was trying to make. It was just a nightmare. They had no passion for the material. They had no desire to make anything that was fresh or original or good or classy."

Lord Of Illusions - Filming The Books Of Blood

By Michael Beeler, Cinefantastique, Vol 26 No 2, February 1995

"There were only two ways a writer could go. You could take the money and run, and let Hollywood do what it will - as many have done. Or, you could take the law into your own hands and see what you could do on your own. Those two films propelled me into directing. I would have been perfectly happy to have been a screenwriter the rest of my life if those had turned out well."

No Apologies

By John Wooley, Bloody Best of Fangoria, No 7, 1988

"For me [Hellraiser] was a chance to see if I could put what I felt I was putting onto the page onto the screen; to form a narrative that would allow me imaginative latitude with the visuals but which wouldn't be too large in terms of set pieces. The only way to do this was to write the novella with the specific intention of filming it. This was the first and only time that I have done that, but it was useful in that I worked through a lot of the visual problems in the novella and the final screenplay didn't take that long to draft."

Hellraiser

By David J Howe,

Starburst, No 110, October 1987

Why then was he so distressed to set eyes upon them? Was it the scars that covered every inch of their bodies, the flesh

cosmetically punctured and sliced and infibulated, then dusted down with ash? Was it the smell of vanilla they brought with them, the

sweetness of which did little to disguise the stench beneath? Or was it that as the light grew, and he scanned them more closely, he

saw nothing of joy, or even humanity, in their maimed faces: only desperation, and an appetite that made his bowels ache to be

voided.

'What city is this?' one of the four enquired. Frank had difficulty guessing the speaker's gender with any certainty. Its clothes, some

of which were sewn to and through its skin, hid its private parts, and there was nothing in the dregs of its voice, or in

its wilfully disfigured features that offered the least clue. When it spoke, the hooks that transfixed the flaps of its eyes and were wed,

by an intricate system of chains passed through flesh and bone alike, to similar hooks through the lower lip, were teased by the motion,

exposing the glistening meat beneath.

'I asked you a question,' it said. Frank made no reply. The name of this city was the last thing on his mind.

'Do you understand?' the figure beside the first speaker demanded. Its voice, unlike that of its companion, was light and breathy - the

voice of an excited girl. Every inch of its head had been tattooed with an intricate grid, and at every intersection of horizontal and

vertical axes, a jewelled pin driven through to the bone. Its tongue was similarly decorated. 'Do you even know who we are?' it asked.

'Yes,' Frank said at last. 'I know.'

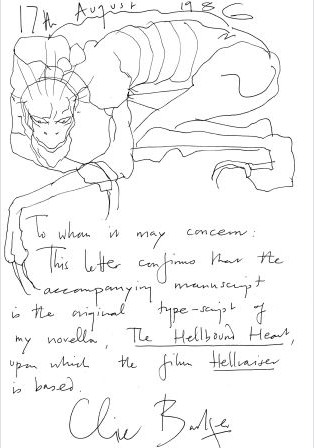

The Hellbound Heart - written in 1985, published in 1986

Doug Bradley: "He's even less a presence in the novella than he is in the first Hellraiser movie where, God knows, he's fairly incidental."

I, Pinhead

By [ ], www.horroronline.com, 1999

Hellraiser Pre-Production

Having completed The Hellbound Heart, Barker set about adapting it into a first draft screenplay, entitling it Hellraiser. A January 1986 working draft screenplay was added to a series of sketches and used as a promotional package to secure funding."I had a friend who had a brother who had a friend... The friend was Oliver Parker, the brother was a guy called Alan Parker and his friend was a fellow called Chris Figg. Chris Figg wanted to produce movies and I wanted to direct a movie and we were both without any experience really in our fields, but two inexperienced people's always more interesting as a combination than one inexperienced person and we kind of gave each other courage, I think."

Resurrection

Documentary on the Anchor Bay Hellraiser DVD, 2000

Christopher Figg: "The whole reason why 'Hellraiser' was made in the first place was as a show reel. There were two of Clive's stories that we wanted to do, but they were technically complicated and the budgets would have been too much for a first time director and producer. I told him we needed a show reel, preferably a story with just three people and a house: that will keep our costs down, and even if we have to make it in 16mm and shoot on weekends, we'll be able to make this because logistically it makes sense. Starting from those constraints, we had a first draft script that was much simpler than the shooting script, and because we were able to get together a decent budget with the help of New World, we've managed to build up on this and get production money on the screen."

Hammering Out Hellraiser

By Philip Nutman, Fangoria, No 65, July 1987

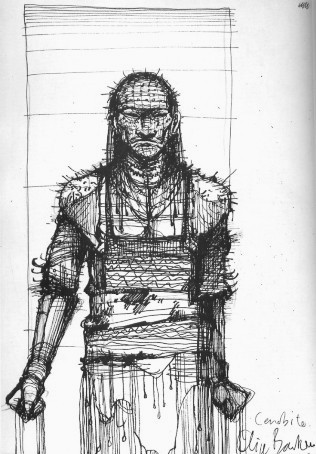

"Alan Parker - who is not the film-maker Alan Parker, but a first rate guy - gave us some seed money to put together a package that contained a lot of drawings that I had done of the cenobites so that I could help anybody who wanted to invest in the movie have a sort of vision of what we trying to make. It wasn't a very sophisticated package: it was the script; maybe half a dozen drawings and a couple of log-lines, just trying to give people a sense of, well, this is what it could be."

Resurrection

Documentary on the Anchor Bay DVD, 2000

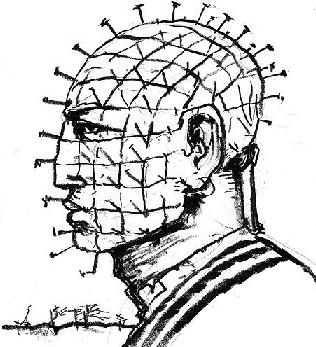

"One of those pages contained the original drawing of Pinhead. And God knows where that drawing came from. It wasn't in a dream. But it came from somewhere in my psyche. I probably drew it around the time that I wrote the story because The Hellbound Heart, upon which Hellraiser is based, contains quite a specific description of Pinhead. The whole geometry of him, the scarification of his face, the pins driven in at each intersection of the lines, and the kind of priestly garb which the Cenobites wore in Hellraiser were also described. So really there was quite a solid jumping-off place for Pinhead. But I don't know where those images came from. Maybe it's great that I don't know. It's one of the secrets of the psyche."

Interview

By John Russo,

Scare Tactics, Dell Publishing, 1992

Christopher Figg:

"In 1986, we were just at the end of the video boom, so we thought horror was our best bet and Clive was obviously happy working in

that vein, so to speak. In our business plan, we pointed out the potentially excellent box office returns against the low cost of genre

films. We worked incredibly hard on the business plan and presentation pack. We'd got as much as possible sorted out upfront: the

artwork, the tag line 'There Are No Limits,' the budget, the schedule and the completion guarantor's letter of intent - all these things are

very important.

"Pinhead was one of the first creatures we scratched out in Clive's house in Crouch End, we thought it would be great

to have this guy with bits and pieces of metal stuck in his face. Lighting-wise, we designed it so that shadows would swirl round his

head. In post-production, it became very clear that Pinhead was going to be the hook on which to hang the marketing."

The Watermelon Factor

By Nigel Matherson, Savvy, Vol 1 No 3, 1994

The January 1986 working draft screenplay detailed a single Cenobite with an indeterminate number of others lurking in the shadows, their appearance not described. Only the single Cenobite glimpsed briefly at the start of the movie ("A hand - profoundly scarred, with its flesh punctured in a dozen places by hooks") is described in detail in the scene in which it confronts Kirsty. At this stage, hooks and scars predominate, rather than an elaborate geometric grid of nails.139 INT. HOSPITAL NIGHT

Darkness.

The bell continues to ring.

And then, lit by a strange, pulsating phosphoresence that has no visible source, a figure appears across the room.

It is a Cenobite. The condition of its flesh appals: the face is a mass of weighted hooks and deep, barely-healed scars. There are

pins driven into its neck and temples, wherever its flesh is exposed. The garments it wears recall both a butcher and a cardinal:

a blood-stained chain-mail apron is set amongst silk robes.

We recognise its voice as that of the creature from the beginning of the film.

Kirsty stares in amazement. In the shadows behind the Cenobite, the other masked forms lurk.

Draft - January 1986

The sketch above matches this initial description of the Cenobite being punctured by a mass of hooks and scars and wearing an apron amongst its robes.

In the first few months of 1986, Barker and his producer Chris Figg secured funding and began to assemble a creative team around them to realise the movie. With respect to the design of the Cenobites, he worked with Bob Keen and Geoff Portass at Image Animation and with Jane Wildgoose who had costume designed many of the Dog Company's later plays. Meeting Wildgoose in April, Barker asked for costume designs for four, possibly five 'super-butchers' whilst refining the look of the scarification and self-mutilation of the Cenobites with Image Animation and in the script. By the next draft in late July 1986 - which acted as the shooting script - the four Cenobites, plus the Engineer, are more fully described and the single Cenobite from the earlier draft is now clearly identified as being the leader, with the now-familiar pattern of pins in his head.

150 INT. HOSPITAL ROOM NIGHT

She flings herself through the door with The Engineer's

breath on her back, and turns -

The doorway has gone. The wall is sealed. She approaches

the wall. The Engineer scratches on the other side ...

Then, she realises that the bell is still ringing. And

there's a foul smell in the air.

She looks around.

She's not alone.

Standing across the room from her, lit by a strange

phosphorescence that has no visible source, are four

extraordinary figures.

They are Cenobites. Each of them is horribly mutilated

by systems of hooks and pins. The garments they wear

are elaborately constructed to marry with their flesh,

laced through skin in places, hooked into bone.

The leader of this quartet has pins driven into his head

at inch intervals. At his side, a woman whose neck is

pinned open like a vivisection specimen. Accompanying

them is a creature whose mouth is wired into a gaping

rectangle - the exposed teeth sharpened to points, and

a fat sweating monster whose eyes are covered by dark

glasses.

When the lead Cenobite speaks, we recognise the voice as

that of the creature from the beginning of the film.

Kirsty stares in amazement.

Draft - 28 July 1986

Geoff Portass: "[Pinhead] was basically Clive's design, as seen on the Hellbound T-shirts. There was a lot of discussion with Clive, then I did a few drawings. First we just had spikes coming out of his head. I wanted it to be more geometrical. Originally he had pins all over the head, but Clive and I thought it would be nice to make it look more like a mask with pins around his chin, over his ears and at the back of his head. We modelled it about six times and did loads of drawings. If you look at the first test pictures that came out of Hellraiser there are actually pins in there rather than nails and the pins got lost - you couldn't see them. So we clipped the ends of the pins off and made our own hollow brass nails that inserted over the top and they were much more visible."

Games Without Frontiers

By Brian J. Robb, Fear, No.6, May/June 1989

Jane Wildgoose: "My notes say that he wanted '1. areas of revealed flesh where some kind of torture has, or is occurring. 2. something associated with butchery involved' and then here we have a very Clive turn of phrase, I've written down, 'repulsive glamour.' And the other notes that I made about what he wanted was that they should be 'magnificent super-butchers'. There would be one or two of them with some 'hangers on' as he put it, and that there would be four or five altogether."

Resurrection

Documentary on the Anchor Bay Hellraiser DVD, 2000

"Nothing springs into my imagination without having inspiration in other things I've seen or experienced. The Cenobites were no

exception. Their design was influenced amongst other things by punk, by Catholicism and by the visits I would take to S & M clubs in

New York and Amsterdam. Of course the make-up and costume designs only do part of the job. We were blessed (if that's the right

word when it comes to such unholy labours) to have marvellous actors beneath the latex, particularly Doug Bradley who played a

character unremarkably dubbed 'Lead Cenobite' in the credits of the first Hellraiser film.

"He so perfectly married threat and elegance that he quickly caught the affections of the audience and was given a name which I

think originated in the make-up studio: Pinhead...

"There was another source of inspiration for the Cenobites; more particularly for Pinhead himself. I had seen a book

containing photographs of African fetishes: sculptures of human heads crudely carved from wood and then pierced with dozens,

sometimes hundreds, of nails and spikes. They were images of rage, the text instructed.

"To rage, then; and to the monsters that embody it. They keep us sane, I think. At least a little."

Hellraiser Box Set

Anchor Bay Hellraiser DVD Box Set Liner Notes, introduction by Clive Barker, July 2004

Hellraiser In Production

"Where, I am regularly asked, does this nightmare come from? Well, I've already made mention of the sado-masochistic

elements, which reflect my own long standing interest in such taboo areas. Associated with that milieu is the punkish influence, which

makes Pinhead the Patron Saint of Piercing. But there's also a streak of priestly deportment and high flown rhetoric in him that

suggests this is a monster who knows his Milton as well as he knows his de Sade, and can probably recite the Mass in Latin

(albeit backwards). His very loquaciousness marks him out from his peers. Many of the monsters who stalked the screens of the

eighties were mute - the Alien was wordless; so were Michael Myers and Jason Vorhees. Some were given to peppering their

murderous sprees with bad puns, like the post-Craven Krueger. But Pinhead glided through his movie appearances dispensing

pseudo-metaphysical insights with as much enthusiasm as he did hooks and gouges.

"In that sense he harks back to the perverse elegance of Dracula, particularly as incarnated by Christopher Lee. Like Lee, Bradley is a

very polite, even reticent, gentleman when out of pins and leather: a loving family man whose perversities are, I'm (reasonably) certain,

limited to his life on screen. If Pinhead is aloof from the agonies he causes, it's because Bradley the actor is intriguingly

dispassionate, and prefers to remain removed from the Grand Guignol that slickens the world he walks in."

Out Of My Skull

Foreword by Clive Barker to The Hellraiser Chronicles edited by Stephen Jones, February 1992

Doug Bradley: "I went to Clive, worried, saying, 'Give me a clue about him.' He was magnificent and irritating at the same time, because he has a wonderful imagination but it's difficult to lock down. He told me he thought of him as a cross between an administrator and a surgeon who's responsible for running a hospital where there are no wards, only operating theatres. As well as being the man who yields the knife, he's the man who has to keep the timetable going. Armed with that I went back to the script and said, 'But how do I play him?'"

Hell's-A-Pop-Pin

By Martyn Clayden, Video World, July 1993

Doug Bradley: "I asked - politely - if everyone would leave the room. I sat and stared in the mirror, letting a flood of

sensations and emotions wash over me. After all the preparation that had gone before, most of my real decisions about the character

and how I wanted to play him were probably made in about twenty minutes right there. On the one hand it is a genuinely unsettling

experience. Where was I? Left behind somewhere, an identity in my head, but according to the mirror not here any more. On the

other, it was thrillingly exciting: this idea, sketch, description was now three dimensional and real.

"I moved my head a little, this way, that way: I went close to the mirror, moved back from it. Then I began to tentatively move my

mouth and face. A frown. A sneer. Raise an eyebrow. Smile. Laugh. Scream. Then words... I'll tear your soul apart... Angels to

some, demons to others...

"To put no finer point on it, I fell in love! I bathed in the sense of power and majesty that the make-up gave me. I felt a sense of

beauty; a dark mangled, inscrutable beauty. This detached, ordered piece of mutilation or self-mutilation, so carefully and lovingly

executed. The head had a sense of peace and stillness about it, quite at odds with the horror the image was presenting. And

beneath it all, a sense of tremendous melancholy, a feeling of a creature fundamentally lost. A line from one of Clive's plays swam

into my mind: 'I am in mourning for my humanity.' At this point there was no back story for the character, but I had discussed this with

Clive and we had agreed that he had once been human. But whether this was yesterday, last week, last year, ten, a hundred, a

thousand years ago, I didn't know. I didn't need to. Sufficient to have that idea lodged into my brain. A perpetual, unconscious

grieving for the man he had once been, for a life and a face he couldn't even remember. And a frozen grief. I felt now that Pinhead

existed in an emotional limbo where neither pain nor pleasure could touch him. A pretty good definition of Hell for me."

Hellraiser

From Chapter Seventeen of Sacred Monsters: Behind The Mask Of The Horror Actor by Doug Bradley, 1996

"The mask is, of course, both a means of concealment and one of confession. It covers the human and reveals the inhuman. The man disappears, and a creature of mythic proportions replaces him: some demon or divinity, a terrible intelligence. There has to be part of the actor that both enjoys and understands the nature of such creatures in order to intimidate us with their presence. When that comprehension is missing, the mask simply sits there, curiously blank. It follows then, that Doug - who is in person a gentleman after the old school, softly spoken and slyly self-deprecating - must have in him somewhere an understanding of the great beast he portrays in the Hellraiser films. Doug is Pinhead, after all. The latex and the costume and the rhetoric aren't worth a damn without him. The arrogance and sadistic glee (it gleams there in the monster's eyes, despite his apparent dispassion), is Doug's gift to the creation, just as surely as the measure of his step or the angle of his head. Without them, the creature would be diminished to a sum of its nails."

Sacred Monsters

Foreword by Clive Barker to Sacred Monsters: Behind The Mask Of The Horror Actor by Doug Bradley, August 1996

Doug Bradley: "The character was presented very much, and rightly so, as an enigma. Clive and I were both trying for a very still, centred kind of figure. There were times early on with Hellraiser, and maybe this was a problem with me coming out of a theatrical tradition and it was the first time I'd been on a film set, that Clive would say to me, over and over again, 'Do less, do less, do less.' It is quite frightening as an actor to find yourself arriving at the point where you are standing still and speaking words. Then you feel that you are not working, but what I then had to do was learn to adapt. If I let my face go dead and did not move it, the Pinhead was speaking volumes. From that point of view, I could hide behind the make-up and rest assured that if I was doing nothing, the make-up certainly was."

Doug Bradley

By J.B. Macabre, World Of Fandom, Vol 2 No 15, Spring 1992

Bob Keen: "95% of what Pinhead is is what Doug Bradley brings to the role. I was very surprised how different his performance was. It was very general-like, someone who stood back and had control and that brought a great strength to the character and a great appeal of that strength. Doug's voice was just fantastic, you hear him and he has those wonderful lines. The whole thing just grew and grew, so I think the look was one thing but if the wrong actor had been wearing this, Pinhead would never be the success that he is."

Resurrection

Documentary on the Anchor Bay DVD, 2000

Peter Atkins: "It's undeniably true that Pinhead - the name and the face - is more well-known than Doug Bradley is. Is it

possible then that it's just the character, the dialogue, the make-up, that have done the trick? Does Doug really have anything to do

with the monster's popularity?

"I can answer that with an emphatic yes. At Clive's invitation, I took over the writing of the Hellraiser series with the second

movie. I've now written three of them. I know just how vital Doug's talent is to the success of the pictures. I've watched Doug at work

on the sound-stage. I've seen him in the dailies. I've seen him in the rough-cuts. I've seen him in the finished movies. He's quite

brilliant. I can sit down and write piss-elegant dialogue for our little black Pope of Hell as much as I want. It's only when an actor of

Doug's calibre gets hold of those lines that they come to life. He never goes for the surface reading, never goes for the obvious, the

hammy - which, God knows, the lines would allow. His interpretations are always subtle, fully-rounded and thoroughly thought

through. He thinks about the role of Pinhead as much as if he was essaying Macbeth or Lear. To Doug, Pinhead is not a silly movie

monster with a latex face and an attitude. He's a character. With subtleties. With light and shade. Doug's ironic, mannered and

darkly knowing performance is absolutely the single most important element in Pinhead's success."

The Astonishing Doug Bradley

Essay by Peter Atkins in Secret City: Strange Tales of London, the 1997 World Fantasy Convention book

"You can't predict what's going to strike the collective psyche because if you could predict it you'd do it more often. The fact is, when

we made Pinhead I was aware this was an image which hadn't been seen on the screen before but I was not prepared for the level of

devotion that that character has aroused in people - and I think 'devotion' is correct because it has faintly Catholic undertones.

"When we were shooting the picture, we got a lot of bad vibes off the producers at New World because they said he wasn't making

any - Freddy was on the rise at that point so he was one of the areas of focus and one of the notes I got repeatedly was he wasn't

making any jokes; why wasn't he making any jokes?

"He's moving really, really slowly and good monsters move fast. He was rather too literary. What they were saying was, this is not

going to work because he wasn't like Freddy and they were very negative about that. And they also went through a phase where they

wanted him to say nothing at all because the other tradition at that time was the Friday 13th stuff, indeed the Halloween stuff which

had Jason and Michael Myers going around being mute and my argument was that Pinhead hailed back to a much earlier tradition of

monsters, primarily, obviously Dracula who is very articulate, very aristocratic. Part of the chill of Dracula surely lies in the fact that he

is very clearly and articulately aware of what he is doing - you feel that this is a penetrating intelligence - and I don't find dumb things

terribly scary - I find intelligence scary, particularly twisted intelligence; it's one of the reasons why Hannibal Lecter is scary, isn't it?

It's because you always feel that he's going to be three jumps ahead of you."

A Tribute To The Hellraiser Series

By Anthony C Ferrante and Rod L Reed, The Dead Beat 3, 1993

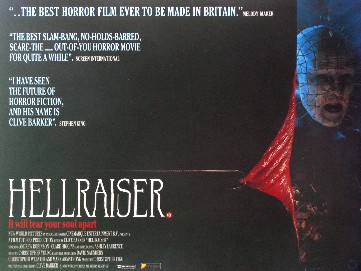

Marketing

"As far as the movie was concerned, we discovered that the Cenobites were attracting a lot of attention. I hadn't anticipated the success of that image. It seems to have seized hold of people's imaginations... If I knew what it was I'd do it again, but the honest truth is I don't know why it's appealed the way it has. As we were going through Hellraiser it became apparent that we were generating images which were actually exciting people and that was very pleasurable because we found we had a critical as well as a commercial hit on our hands."

Go Straight To Hell

By Edwin Pouncey, New Musical Express, 2 April 1988

"It quickly became clear to all of us that he had made a mark on the consciousness of the audience out of all proportion to his screen time. The credit for this lies both with the actor behind the pins, Doug Bradley, and to the sometime team of Bob Keen and Geoff Portass. Together, they made the nightmare breathe."

Out Of My Skull

Foreword by Clive Barker to The Hellraiser Chronicles edited by Stephen Jones, February 1992

"I never understood the thing with Pinhead. Truly, from the bottom of my heart, I never expected the stuff on the sneak preview cards: 'The guy with the pins in his face is real sexy'. 'Love the dude with the pins in his face'. I intended the Cenobites to be elegant, strange but sexy?"

Future Shockers

By Maitland McDonagh, Film Comment, Vol 26, No 1, Jan-Feb 1990

Hellraiser UK Theatrical Quad Poster, 1987

Doug Bradley: "The first choice was to put Skinned Frank on the poster, but they were told no, they couldn't do that. So Pinhead was actually second choice. Maybe that came from Clive, because what we get in that image of Pinhead with the box is the heart of the Hellraiser mythology. If you put the Engineer or the skinned man on the poster, it's an amazing image but it's just an image, and it could come from any movie. When you put Pinhead on the poster, holding this puzzle box out - 'Come on, have a try' - then you're presenting something very specific. The big success of Pinhead is because the image is so original, so startling. It is just an incredible image to look at, and that made a big difference in terms of the public's perception of the movie."

I, Pinhead

By [ ], www.horroronline.com, 1999

Sequels

"The extraordinary thing is this: that the moment you make a story or create an image that finds favour with an audience, you've

effectively lost it. It toddles off, the little bastard; it becomes the property of the fans. It's they who create around it their own

mythologies; who make sequels and prequels in their imagination; who point out the inconsistencies in your plotting. I can envisage

no greater compliment. What more could a writer or a film maker ever ask, than that their fiction be embraced and become part of the

dream-lives of people who it's likely he'll never even meet?

"Hellraiser, and to a lesser extent the novella upon which it's based, The Hellbound Heart, were pieces of work that elicited these

welcome responses from their first appearance on page and screen. That the Lament Configuration and the Cenobites its solving

summons - Pinhead especially, of course - be taken to the hearts and imaginations of so many healthily perverse folks around the

world was both surprising and reassuring to me. The former because the film had been made very cheaply - as much to prove to

myself and the overlords of Hollywood that I could turn a modest amount of money into a marketable film; the latter because the

images and ideas in the picture were extremely dark, and I was delighted that there was a sizeable audience for a horror film that

didn't dice adolescents in the shower, or have its tongue buried so deeply in its cheek it could lick out its ear from the inside.

"But back to what I was saying about the work being possessed by others. After Hellraiser came Hellbound: Hellraiser II in which writer

Peter Atkins and director Tony Randel took the open threads of the first movie and wove their own sequel. It wasn't the movie I would

have made, but it was immensely interesting to see how other minds and other talents dealt with the ideas; exploring avenues I hadn't

even contemplated when I first set pen to paper."

Hellraiser, Book 1

Introduction by Clive Barker to the Hellraiser graphic novel, Book 1, December 1989

Doug Bradley: "The success of the character in the first film is largely about his sense of complete mystery and sense of power - because you don't see him very much. The first time you see him it's enigmatic, you don't know who he is, why he is, where he is, how he is, what does he want, what does he do, where does he come from, where is he going when this is all over? And at the end of the movie, really those questions have not been answered. Once you move onto a sequel, everything changes."

Lost In The Labyrinth

Documentary on the Anchor Bay Hellbound DVD, 2000

Peter Atkins: "The development of the Cenobites is something that Clive was very keen to do once New World suggested a sequel. Hellbound reveals details about the Cenobites that we didn't know before. We learn who they were and why they became what they are."

Hellbound : Breaking The Last Taboo

By Philip Nutman, Fangoria, No 76, August 1988

Pete Atkins: "In many ways, this [Hellraiser 3] is both a sequel and a prequel to Hellbound. Not chronologically, but conceptually. It answers a lot of questions left dangling from that picture concerning who Pinhead is, how and why he became what he is, what it means to be Pinhead, etc. One of the aspects of the script I'm most pleased with is the fact that it's very much the completion of a trilogy; it's not just a new adventure using the mythos... It's very much an examination of the rules of hell, and by freeing Pinhead from those rules, we discover more about him. You could call this Pinhead Unbound."

The Long Road To Hell

By Philip Nutman, Gorezone, No 22, April 1992

Doug Bradley: "Pete's done a terrific job. He and I have had

hours of discussions concerning Pinhead's character since we finished

Hellbound. Between us, we've really discovered who this demon is and,

equally as important, who he was as a human being.

"He has given me a a more sinister, glibly malevolent Pinhead to work

with. The crucial aspect is that he's out of the box. In the past he

was constrained by the Lament Configuration and had to play by the

rules. Now there are no rules, which makes Pinhead even more dangerous

in a way. So it really doesn't matter if we're seeing the character in

an obviously American setting. The character is strong enough to exist

in any environment because he's far more powerful than either Michael

Myers or Jason."

Hellraiser III - Welcome To Club Dead

By Philip Nutman,

Fangoria, No 110, March 1992

Doug Bradley: "[Pinhead] was an English army officer in an

unspecified place and time, though roughly in the Far East in the late

20's or early 30's. He was a very pucker Englishman, a public school

type who went straight into the army. He felt terribly out of place

and unfulfilled because he was only there through family tradition.

So from his sterile viewpoint, what he hears of the Lament box is very

appealing. I see him alone in his Nissen hut trying to solve the

puzzle - which he obviously does, and is transformed into Pinhead.

"I don't see him as the first Cenobite. Of the four we know about, he

is the leader, but the Cenobites have been around for centuries. To me,

Pinhead is the chief Cenobite of the 20th Century."

The Pride of Pinhead

By Philip Nutman, Fangoria, No 82, May 1989

"I have no contractual control over any of this

material. The Hellraiser concept was sold outright

for the million dollars they gave me to do the first

movie. In hindsight, it's a Faustian pact that echoes

the plot of the movie, but I didn't know that at the

time. And, to be fair, the film company were taking on

a guy who'd never directed before. So I'm not going to

whine about what these guys have done with the stuff,

because they gave me a million dollars to make

Hellraiser. It's the same with Candyman. If somebody

puts up $10 million to make a Candyman movie, they buy

the rights to do what they want to do, so if they want

to make Candyman into a stand-up comedian there's not

a whole lot I can do about it.

"It's a weird situation. Here we are talking

about a movie franchise which has long since ceased to

have anything to do with my original conception. It's

Pinhead the plastic model, Pinhead the horror icon...

Did you know he was on the Tonight show with Mel Gibson,

for instance? It's tough when the villain of your

movie takes a pin out of his head in order to fix Mel

Gibson's coat because it's frayed. How can you expect

an audience to then go into a movie house and be scared

by the character after something like that?"

Clive Barker - Lord Of Illusions

By Nigel Lloyd,

SFX, No 16, September 1996

"One of the obvious limitations is that the more often you see a villain, the less scary they are. It's the law of diminishing returns.... I'm very aware that that's a problem. Particularly the 'Hellraiser' series. You know, Pinhead is a plastic model, a jigsaw and a phone card - a very well exposed face. The first thrill you had of seeing that character in the first movie...has long since gone. And you can never really recapture that first encounter. So I thought if I'm going to make another series of horror movies, why not base it around the hero...Instead of having to warm over horror images that you've seen in previous pictures, you can actually say, 'OK, let's do something really neat and new.'"

Lord Of Illusions - Filming The Books Of Blood

By Michael Beeler, Cinefantastique, Vol 26 No 2, February 1995

Peter Atkins: "I wish I could take credit but I can't and it's very fitting who does take the credit for this: Doug's very kind to say

there are some some good lines in that one [Bloodline]; one of the best lines in it was not written by me and happens right at the end.

At the time we thought it was going to be the last words Pinhead would ever utter on screen because we figured the series was going

to be over, we didn't know there were going to be direct-to-video sequels.

"I'd already done three sets of free post-production rewrites for them but I was off writing Wishmaster, so they brought in Rand Ravich

to write a couple of scenes and he did a fine job, but almost the last important line Pinhead speaks was actually written by Clive.

They asked Clive to come and view the edit - and I'd given him lots of good shit to say beforehand like, 'Do I look like someone who

cares what God thinks?', all that good stuff - but the last line was just a free gift from Clive, so I thought it was very fitting that the guy

who created the whole thing in the first place wrapped it up. And the line is: 'I am so exquisitely empty.'"

Hellraiser Reunion

Hellraiser reunion panel at Monster Mania 5, 20 May 2006

"In a way the movies belong to different people now. Maybe arguably they still belong to Doug who has been the constant through all these movies and is, after all, the icon at the heart of the Hellraiser movies. And they belong to the fans and I think that's important too, they belong to people who love those movies perhaps more than I do."

Resurrection

Documentary on the Anchor Bay Hellraiser DVD, 2000

Doug Bradley: "I'm still enjoying doing the movies, still having fun doing them, still finding fresh territory to

explore myself. And I always try to make sure those lines of communication are well and truly open with the director.

The last thing I would want would be any feeling from the director that I'm the guy who does Pinhead, and I know

everything about it and therefore I can't be directed. I always go to the director and say, 'Look, I do know what I'm

doing here but any new thoughts or ideas or anything you feel is amiss or something new we could throw in, I'm

fully open to suggestions.'

"It also helped with Parts 7 and 8 that they were again directed by Rick Bota, who directed Hellseeker, Part 6.

I got on very, very well with him, so it was great to have the chance to go back and work with someone who I knew

got [it] and that I'd worked with previously. It's actually the first time in the whole series that I worked with the same

director twice, so that was certainly an advantage. If there are going to be any more - and who knows at this

stage - I have no barriers to going there again."

The Face Of Evil

By Joseph McCabe, Starburst, Special No 66, [October] 2004

Scarlet Gospels

Currently awaiting its final polish is the novel The Scarlet Gospels from the pen of Clive Barker. Setting Pinhead against another of Barker's literary creations, Harry D'Amour, in an apocalyptic setting, we are promised a metaphysical but final ending to the High Priest of Hell. At least, an ending on the page... We suspect that Pinhead will be drawing breath on screen long after the final page has been turned on him by his original creator - the iconic leader of the Order of the Gash outlasting his maker, alive in the hearts and minds of those who have adopted him as more than the sum of his parts...

"I'd certainly been thinking for a very long time about how I would eventually bring

eloquent and respectful closure to the life of a character who has been very good to me. But then I realised that to be respectful and

all that good stuff, I also needed to be epic because there was a sense that there was an epic structure somewhere behind him that

the films didn't show and my original thought was that I would simply tell a tale of closure that was the size of the tale which

introduced him - thirty thousand words - and then I thought that does him a terrible injustice, because we are teased over the films

with a sense that there is something, some huge structure there in which he belongs, in which he has a significant part and how can I

write that, how can I bring him to his final act without first taking him, taking my readers through what that system is - in other words,

taking them down to Hell and showing them what the Order of the Cenobites are and where he belongs in them and what the

consequences of rebellion on his part might be, and so on and so forth...

"You can start this book and have read nothing, seen nothing - it's fine. If you have seen the first movie, that's fine. If you've seen

the second movie, probably that's fine too. If you've read the novella - The Hellbound Heart - surely, that's fine too."

Abarat. Abarat. Abarat. Abarat... Abarat!

By Phil and Sarah Stokes, 13 and 20 March 2006 (note: full text here)

"It's going to be a big book now - I never thought it would be a big book. But once I started to write it, I realised that in a way

I knew a lot of things about hell and a lot about Pinhead, that character, that had never appeared in any movie or comic

book or anything. These are things which are in my head - and it had been in my head for many years - but that I have

never written about. So I'm putting all of that into the book. I'm doing my very best to really develop the mythology and to

make this Clive Barker's definitive book of hell...

"So its called the 'Scarlet Gospels' - the thought that I have had for this collection of short fiction - but it actually seems to

belong to this novel - it seems to want to belong to this novel... it will be a single volume. This will be a novel on its own I

think. And then we will do the collection of short fiction at a later point, I have got a lot of short fiction, which we have not

been published.

"And what I haven't realized until I have started writing, was how passionate I felt about the character of Pinhead. I suppose

part of it is that I become very familiar with the image of the - like everybody has - the toys, the game, obviously the films

and so on. But when I actually went back and wrote about him, wrote in his voice, as it were, I realized that he became

more interesting than he had a chance to be in most of the movies. Most of the movies make him into just a simple villain,

who is just there, doing this thing, he's there to cause trouble. And I wanted to write something more complex about him, I

think he is quite a complex character. You know he isn't Freddy Krueger, he isn't Jason Voorhees, he is something more

eloquent and possibly elegant. And so I really wanted to explore this character and really give him a chance to speak one

last time - very eloquently."

Clive Barker On The Phone

By [Thomas Hemmerich], That's Clive!, 29 March 2005

"Here's been this essentially two-dimensional being... taking this character that has been denuded of any elegance that he may have once had and coarsened over a period of movies and putting him into a book in which Christ appears and Lucifer appears has been quite a challenge... My hope is that a little way into this book people will almost entirely forget the cinematic incarnation of this fellow and start to think of him as a literary character again."

You Called, He Came...

By Phil and Sarah Stokes, 2 and 3 June 2006 (note: full text here)